Sioux Natives buy back Sacred Land: Lakota Stake Their Claim on the Earth

Nestled in the southwest corner of South Dakota, the Black Hills rise out of the Great Plains like a new forest growing from its burnt ancestor. The surrounding scenery is light and dry like kindling, but the hills rise into view covered in lush dark pine trees. The ubiquitous “black” of the Black Hills is actually a deep evergreen. These hills, the Lakota’s most sacred land, pulse with life.

In the heart of the Black Hills, the forest gives way to a wide clearing. This privately owned land, The Reynolds Prairie Ranches, is called Pe’ Sla by the Lakota and is an especially sacred site within the Black Hills. According to the Lakota, Pe’ Sla is where the Morning Star fell to earth and killed seven women. To honor them, the Morning Star placed the soul of each woman into a star of the Pleiades constellation.

When the government seized the Black Hills from the Lakota in 1877, they sold off parcels of the future national park, including Pe’ Sla, to private owners. The Lakota believe that the Black Hills were stolen from them; now, they are uniting to buy Pe’ Sla back.

Pe’ Sla is only the beginning of the Lakota story; this purchase represents an entire movement towards the resurgence of a rich culture and strong communities.

Lakota in the Black Hills

The true name for the “Great Sioux Nation” is Oceti Sakowin, meaning “Seven Council Fires.” Sioux itself is not a word in any language, but is short for Nadowessioux, a combination of Chippewa—an enemy tribe—and French words, meaning “dirty snakes.” Sioux has come to describe the Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota peoples of the Oceti Sakowin.

In 1851, the Lakota signed the Fort Laramie Treaty with the United States government, outlining their territory. The land stretched across the entire west side of South Dakota, reaching into North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming and Nebraska, with the Black Hills at its center.

To Bellecourt and many American Indians, the Lakota’s most sacred land was taken from them for the yellow rock in the ground.

The government re-negotiated the treaty in 1868, officially creating the “Great Sioux Reservation,” shrinking Lakota territory but keeping the Black Hills in the reservation. The treaty stated, “No white person or persons shall be permitted to settle upon or occupy any portion of the territory, or without the consent of the Indians to pass through the same.” Then, in 1874, General Custer found gold in the Black Hills.

Despite the fact that the Black Hills belonged to the Lakota under an internationally recognized treaty, the American government passed an act of Congress in 1877 to seize them.

“In return for the land, the government promised them that they would be able to sustain life forever,” said Clyde Bellecourt, co-founder and director of the American Indian Movement. “When they find gold or they find uranium or they find rich farmland or water, the grass quits growing, the sun quits shining, the river quits flowing. The corporations come in and steal everything.” To Bellecourt and many American Indians, the Lakota’s most sacred land was taken from them for the yellow rock in the ground.

The next 23 years were marked with battles over the land promised to the Indians in the treaties.

The Massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890 marked the end of the Indian wars of the 19th century. Many considered the slaughter of surrendered, innocent, unarmed Lakota—mostly women, children, and elderly—as revenge for the Indian victory at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1786.

Since then, the fight for Indian land has been a legal one. In 1979, the US Court of Claims wrote, “A more ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealing will never, in all probability, be found in our history,” in reference to the government taking the Black Hills.

In 1980, the Supreme Court ordered the US government pay $105 million in reparations to the Oceti Sakowin for taking the Black Hills. The Oceti Sakowin continue to reject this ruling, stating that the Black Hills were never for sale and that by accepting the money, they would cede their claim to the land.

James Anaya, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, toured the United States in April and May 2012.

“The Black Hills in South Dakota… hold profound religious and cultural significance to tribes,” Anaya said. “It is important to note, in this regard, that securing the rights of indigenous peoples to their lands is of central importance to indigenous peoples’ socio-economic development, self-determination, and cultural integrity.”

Much of the media and Lakota community interpreted this as a call for the US government to return the Black Hills to the Lakota.

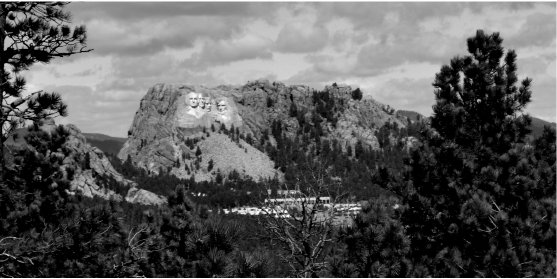

However, the idea of returning the entirety of the Black Hills to the Oceti Sakowin angers many Americans because those hills hold a national icon, Mount Rushmore.

Pe’ Sla

Now the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is moving forward to purchase Pe’ Sla for the Oceti Sakowin. Currently, the Reynolds family is selling 1,942 acres of the Reynolds Prairie Ranches, located within the Black Hills. Most of Pe’ Sla lies in its boundaries.

The Reynolds family has owned the land for 100 years and has always allowed the Oceti Sakowin to perform annual spiritual ceremonies on their property, but the Oceti Sakowin fear future owners might not.

James Anaya released a statement calling on the US and South Dakota governments to consult the native communities in regards to the auction.

The auction was scheduled for August 25, but the Reynolds family cancelled the auction August 24. They have not explained why.

“Because this was considered a sacred site, an appraisal really didn’t have a lot of meaning.” Schmidt said. “You can’t put a value on a spiritual site.”

The Rosebud Sioux Tribe had intended on bidding on one of the five parcels of land for sale; when the auction was cancelled, the tribe offered to purchase the entire 1,942 acres. The Rosebud Sioux Tribe reached an agreement with the Reynolds family of $9 million for the entire 1,942 acres of Pe’ Sla. The deal required an immediate $900,000 down-payment which Indian Land Tenure loaned to the tribe; the tribe has already paid back that loan with interest. The tribe has until November 30th to pay the remaining $8.1 million and will take out another loan to do so.

Vernon “Ike” Schmidt, the executive director of Tribal Land Enterprise, an organization with the purpose of acquiring land for the reservation, said the final price settled upon was probably three or four times the fair market value.

“Because this was considered a sacred site, an appraisal really didn’t have a lot of meaning.” Schmidt said. “You can’t put a value on a spiritual site.”

Members of the community differ in their opinion of the sale. It angers many who do not believe in buying land that already belongs to them according to the treaty.

“It’s a shame what happened, and it’s a shame that… tribes have to buy [Pe’ Sla] back in order to preserve it as a sacred site, to have it not be developed commercially or residentially,” Schmidt said. “We have to turn around and buy our land back in order to preserve the sacred site.”

While divisive among the Lakota community, the unity around the Pe’ Sla purchase is unprecedented.

Beyond the Land

Land claims are not the only part of the Lakota story making headlines. In the past year, the media has frequently reported on the Lakota community, particularly on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

Much of the media portrayal focuses on the negative statistics of reservation life. On the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, unemployment fluctuates between 85 and 95 percent, and most jobs are provided by the tribal government. Ninety-seven percent of the population lives below the federal poverty line. More than half the reservation’s adults battle addiction and disease such as alcoholism, diabetes, heart disease, cancer and malnutrition. The teenage suicide rate is 150 percent higher than the national average, and the average life expectancy—48 for men and 52 for women, as of 2007—is the lowest in the Western Hemisphere, with the exception of Haiti.

But a cultural resurgence and a force of dedicated individuals are changing these statistics. Rather than continuing to depend on an unreliable government, indigenous individuals have begun many initiatives from within their communities.

In the 1970s, American Indians made their voices heard with the American Indian Movement. While controversial, AIM was proactive and encouraged more self-reliant communities.

“When the American Indian Movement formed in July of 1968 we discovered that 75 percent of all the energy resources, which includes gold and uranium and silver and good farm land were still on our land,” said Bellecourt. “We would never give up another inch; we would give our life for what we believed in.”

Bellecourt does not believe in relying on the government for basic needs such as housing, education and health care promised in the Fort Laramie Treaty.

“We have our own job training programs, we have our own housing programs, we have two clinics,” he said. “We can’t depend on anybody anymore; we have to do it ourselves because the government can cut you off at any time.”

Bellecourt says his job training programs are widely successful. He has trained 45,000 people, taking 35,000 off of welfare over the course of 35 years.

Other efforts are taking place that focus on traditional Lakota practices, particularly to treat mental health conditions and addiction. Healing ceremonies, such as inipis, or sweat lodges, are frequently used for addiction therapy. Additionally, the Sweetgrass Suicide Prevention Program, a grassroots community effort, utilizes traditional cultural methods for healing.

The dedicated members of the Lakota tribe and the resurgence of traditional Lakota culture have created more hope on the reservations than ever before. While many remain divided over the course their communities should take, each community is making strides towards better living standards for all, and they are doing so by their own choice, rather than by the will of the government.

Culture Blooms in the Heart of the Country

The Lakota cultural resurgence is present not only on the reservations, but also here in Washington, DC.

On a clear September morning, a small teepee village resonates with the sound of drumbeats beneath the Washington Monument’s watchful eye. A banner reading “Prayer Vigil for the Earth” is spread between two teepees.

Inside the circle, there are American Indian children dancing in their traditional dancing clothes beside a fire and a large drum. People of all ethnicities and faiths are observing.

“The native people dancing with the non-native people, it was very moving,” said Sharon Franquemont, who organized the event. She is the daughter of a Lakota man and says Lakota blood runs through her veins.

Franquemont began the Prayer Vigil for the Earth in 1993 after having a vision on the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation.

“There was a vision that the 500 years beforehand had been so rough on indigenous people all around the world, that we’d like the 500 next years to be very different, and not just for indigenous peoples, but all peoples,” she said.

Among the different tents are representatives of many faiths, from Christianity to Buddhism. The Vigil is not exclusively for American Indians.

“The purpose is for people to share, for 33 hours, their prayers and traditions in an atmosphere of respect and love,” Franquemont said. “And so it’s a chance for humanity to practice peace with each other, particularly around religion and spiritual traditions.”

“We would never give up another inch; we would give our life for what we believed in.”

Franquemont believes that the Vigil gives hope and encouragement to the youth, but that the Vigil is bigger than just cultural resurgence and empowering youth.

“A quote of my Native American father, I think, summarizes what we’re trying to do: If you prick the finger of a white person, the blood runs red; if you prick the finger of a yellow person, the blood runs red; if you prick the finger of a black person, the blood runs red; and if you prick the finger of a red person, the blood runs red,” he said. “So that proves that we’re all one; skin color doesn’t mean anything. And that’s what this vigil is about: for us to remember that we’re really all one as we welcome Mother Earth—to learn to treat each other with love and respect.”