Shaping Policy in Nicaragua: International Relations From a Different Country — AU Professors Share Their Story

According to AU professor Dr. Elizabeth Cohn, Ronald Reagan’s presidential legacy has been whitewashed. This is not a reactionary political slogan; it is a conviction born of her work as founder and director of the Central American Historical Institute from 1982 to 1988 — the height of the Reagan Administration’s covert support for anti-government “contras” in Nicaragua.

During that same time, AU professor and Distinguished Diplomat-in-Residence Anthony Quainton was serving as the US Ambassador to Nicaragua — a position that eventually forced him to confront his own misalignment with the Reagan Administration’s priorities and strategy in Central America.

Students of the social sciences are likely familiar with the maxim, “where you stand depends on where you sit,” a reminder that context matters in understandings of political and historical phenomena. I spoke to Cohn and Quainton to hear their stories, which illustrate this principle in the case of US involvement in Nicaragua.

Cohn was 25 years old in 1982, when the Jesuits of Central America asked her to found and direct the Central American Historical Institute, a progressive think tank headquartered at Georgetown University. The Jesuits — active in liberation theology movements such as the Sandinista National Liberation Front’s 1979 revolutionary overthrow of the Somoza dynasty — wanted Cohn to take the lead in providing accurate, non-governmental information about Nicaragua to US policymakers, activists, journalists and academics. Soon, researchers in Nicaragua were sending telex messages to Cohn in DC, which she then compiled into reports and mailed out to a list of subscribers.

Cohn notes that even though Central America was the foreign policy issue of the 1980s, it was difficult to get accurate, in-depth information about conditions on the ground, especially if it contradicted the official position of the Reagan Administration.

The Central American Historical Institute quickly became a leading source of reporting and analysis on Nicaragua, surpassing Cohn’s own expectations of her organization’s influence. She recalls being surprised to learn that one of her reports had appeared as “Exhibit J” when Nicaragua sued the US in the World Court in 1984 for illegally putting naval mines in Nicaraguan harbors.

For Quainton, too, the media played a memorable role in his tenure as US Ambassador to Nicaragua. He remembers his initial arrival in Nicaragua after his appointment under Reagan, stepping off the plane at Sandino International Airport in Managua on March 15, 1982 and being met with a barrage of media cameras and microphones. One reporter asked him to comment on the state of emergency that had been declared in Nicaragua while he was in transit.

Unbeknownst to Quainton, CIA-backed Nicaraguan rebels had blown up two major bridges during his flight there. “I was completely blindsided,” he recalls. “Our relationship with the Sandinistas pretty much went downhill every day from there.”

As evidence, Quainton points to the framed political cartoons from Nicaraguan newspapers on the wall of his office in the School of International Service, caricatures of him with Sandinista leaders. Quainton remembers Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega as “aloof” and “hard to know.”

“Ortega is not,” Quainton says with diplomatic understatement, “a very nice man.”

“I wouldn’t say the information we provided was neutral. Things were so politicized. It was important to provide information that was more accurate, less one-sided. I saw myself as an honest broker, a patriot.”

Cartoons of a different kind illustrate one reason for the tense diplomatic relations, according to Cohn. In 1984, a member of the advocacy group Witness for Peace approached her with a comic book-style “Freedom Fighter’s Manual,” which encouraged Nicaraguans to sabotage the Sandinista government by cutting power lines, throwing Molotov cocktails at police stations, damaging automobiles and stealing government food supplies. An Associated Press reporter confirmed that it had been published by the CIA for the rebel group. Over 85 newspapers picked up the story and severely undermined the credibility of the Reagan Administration’s official position that the US did not seek to overthrow Ortega. Investigations into the first manual revealed another CIA manual, this one advocating assassination.

After the publication of the comic book story and Reagan’s landslide re-election, the political climate changed. “It became a lot more difficult to challenge the administration,” Cohn says. And challenging the administration became the goal of her organization. “I wouldn’t say the information we provided was neutral. Things were so politicized,” she recalls, “it was important to provide information that was more accurate, less one-sided. I saw myself as an honest broker, a patriot.”

Meanwhile, Quainton too was beginning to understand the stubbornness of the White House’s position on Nicaragua. Strongly influenced by CIA Director William Casey’s preference for regime change, Reagan’s position, according to Quainton, amounted to: “As soon as Ortega goes, we’ll talk.”

Quainton said, “They figured — correctly — that I was somewhat more sympathetic than Washington.” This was partly due to the State Department’s general preference for negotiation, and partly due to what Cohn jokingly refers to as the “Sandal-istas” — American groups, often religious, that traveled to Nicaragua to demonstrate in opposition to the poorly concealed US support for the contras. Quainton recalls these groups as being “very outspoken, very emotional.”

Despite perceptions by such visitors that Quainton was too much of a hard-liner, by 1983 it was clear that he and Reagan were not “on the same wavelength.” Quainton had been contacted by a senior White House official, who told him to report more bad news about the Sandinistas. “I can’t do that. We report all the news,” he replied. In October, a bipartisan commission on Central America, led by Henry Kissinger, visited Nicaragua on a fact-finding mission, culminating in what Quainton calls “a disastrous day for diplomacy.” After asking Quainton if he had to “shake hands with that son-of-a-bitch,” Kissinger went into a meeting with Ortega in a foul mood, and, after listening to Ortega deliver a long diatribe against the US, walked out of the room without saying a word.

Quainton had been contacted by a senior White House official, who told him to report more bad news about the Sandinistas. “I can’t do that. We report all the news.”

Having been pressed repeatedly by the commission on whether Reagan agreed with the State Department’s attempts to negotiate with Ortega, Quainton was not entirely surprised to receive a call from the Deputy Secretary of State a few months later announcing that the president was going to make some changes in Nicaragua. Six months after learning he had lost the president’s confidence, Quainton left Nicaragua and became the ambassador to Kuwait. Being given another appointment after being fired is unusual in the State Department. “More typically, when you leave, you’re done,” Quainton said. But Secretary of State George Shultz argued that Quainton had done nothing wrong and did not deserve to be punished. In Quainton’s words, it was a matter of Reagan “looking for a different style of ambassador, someone who was going to be much more hard-line.”

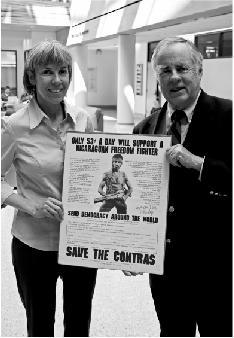

Despite traveling to Nicaragua a dozen times between 1982 and 1988, Cohn does not recall ever meeting Quainton there, though they are now friendly colleagues, both teaching in SIS. The Central American Historical Institute was not very interested in the official US position that they would have gotten from the embassy, she recalls dryly, noting that their research interests lay more in the direction of the border regions with Honduras where the contras were based. She is still angry about Reagan’s covert and, she argues, impeachable support for the Nicaraguan contras.

Quainton is more sanguine. He says his experience in Nicaragua didn’t change his perception of representing US interests abroad. In his subsequent ambassadorships to Kuwait and Peru, there was much less of a gap between public opinion and White House policy. No cheerleader for either Ortega’s government or the US backing of the contras, throughout his time in Nicaragua Quainton remained dedicated to making sure both the good and bad aspects of the Sandinista governance made it back to the States.

A commitment to communicating the nuanced truth guided both Quainton’s and Cohn’s experiences in Nicaragua. Far from being content to toe the Reagan Administration’s line — and despite considerable pressure to do so — each sought to present the complexity of the situation to the US government and the public. The experiences of these AU professors remind us to be critical of official policies and the way they are remembered and to be sensitive to the context and source of information.