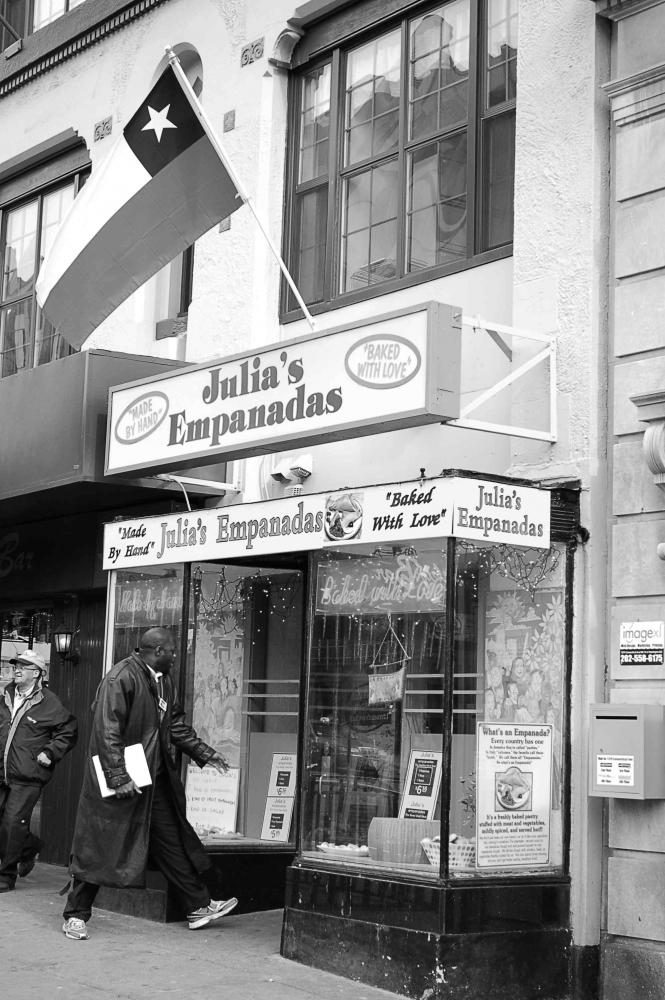

An Immigrant’s Recipe For Success: Julia’s Empanadas

February 16, 2011

Julia’s Empanadas, Hohman’s popular restaurant chain, has supported her and her family since its opening 17 years ago. On any given Saturday night, the small shop in Dupont Circle is packed with hungry and eager customers. Hohman, who emigrated from Chile in 1971, has worked hard to achieve the comfortable life she has today.

“I am what you call here, a workaholic,” Hohman said. She has put in years of 80-hour work weeks. “I think if you’re a hard worker no matter what, you’re going to make it. Some people don’t want to make it.”

Unfortunately, Hohman’s remarkable story belies the tales of millions of other Latin American immigrants. With the worst US economy in decades, The New York Times has reported several anecdotal stories of reverse migration—immigrants returning to their home countries.

While Hohman’s life has meandered through plenty of hard times and struggles, her love for cooking has always been a constant and the key to her success.

“I always liked to cook,” Hohman said. “Even when I was 10 or 11 years old, my mother was sick and I used to cook for her.”

Hohman’s parents both died when she was young, leaving her to care for her younger sister and brother. In 1971, she decided to travel to the US for a few months to look for work. Those few months turned into a lifetime when Hohman’s sister called from Chile, advising her not to return because of political uncertainty. President Salvador Allende had become the first elected Marxist head of state in the western hemisphere, creating a chaotic atmosphere and, according to Hohman, a lack of opportunities back home.

Feeling a greater sense of urgency, Hohman was able to learn English quickly by always carrying around a dictionary. This — along with English classes from Chilean grade school — made adapting much easier. Hohman was soon able to find a job in a hotel restaurant in Silver Spring, where she lived for six years.

“The chef was teaching me preparation for a buffet, and banquet preparation,” she said. “That’s how I started learning.”

While working in Silver Spring, Hohman was introduced to the man who would become her husband and Julia’s Empanadas co-owner, William Hohman.

“It was like a blind date,” said Hohman. “My friend asked me if I had a boyfriend, and I said ‘boyfriend?’ I didn’t even remember what that was. I was working 80 hours a week, so I seldom had a chance to meet anyone. And my friends, I lost them. I never went anywhere, only work.”

Years later, Hohman and her husband opened Julia’s Empanadas, which eventually grew into a chain of four restaurants. Hohman was working at another hotel when the restaurant started up and traveled to Julia’s Empanadas late at night to chop up onions and other ingredients for the empanadas. Now the restaurant has electric machines, a bigger staff and produces over 5,000 empanadas a day. Hohman’s success story has even reached two of Chile’s major newspapers, El Mercurio and La Tercera.

Hohman’s success distinguishes her from the many immigrants in the US who struggle to make ends meet. For immigrants lucky enough to have migrated through legal channels, there’s some structural support that may help. Bryan Griffith, spokesman for the Center for Immigration Studies, explains that documented immigrants now have the support of a social safety net, unlike the great wave of immigrants who came from Europe in the early 1900s.

“The answer for immigrants back then was: be successful, or go home,” Griffith said.

But the success of immigrants in the US is now highly dependent on education level, according to Amy Oliver, a philosophy professor at AU who specializes in Latin American thought. “For skilled and educated immigrants, I think success is as attainable or more so than it was 30 years ago,” Oliver said. “Unskilled immigrants have always had a more difficult experience, perhaps more so now because of the economic recession.”

Hohman maintains that her success did not happen by chance. Rather, it resulted from her sheer determination. “A lot of people say I’m lucky,” she said. “But I worked hard. I continue to work hard. I haven’t taken a vacation in 20 years.”

Photo by Amberley Romo