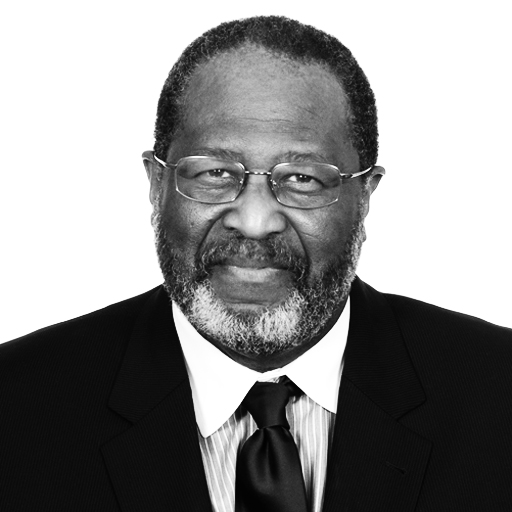

Professor Profile: Richard Cambridge

November 18, 2009

Who knew that mild-mannered Richard Cambridge, SIS professor and strident Marxist, spent the last thirty years behind the walls of the World Bank? Incongruous? No, it’s just a window into the multifarious nature of one of AU’s most dynamic.

Born in the former British colony of Guyana, South America, Cambridge attended Queens College, an exclusive British preparatory school. He grew up under the guidance of his father, a luminary of the Guyanese independence movement. At 18, Cambridge came to the US on a Fulbright Scholarship in 1967 during the Vietnam War — cementing his budding political activism. Through his outspoken dissent on the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, he became acquainted with Hubert Humphrey, the vice president under Lyndon Johnson, who was a professor there at the time. “Young man, you know you’re agitating a lot,” Humphrey said. “But you’re not doing anything. If you really want to do something, I’m prepared to help you. What is it that you want to do?”

Cambridge wanted to make a difference. Humphrey encouraged him to pursue graduate work in the United States, and wrote his recommendation for the Johns Hopkins School of International Studies (SAIS) , where he earned his Ph.D in Economics. He completed a portion of his graduate work at the Bologna Center of SAIS in Bologna, Italy, where the political climate was even more radical–it was the only Communist-controlled city in Italy.

From Bologna, Cambridge had the opportunity to travel to Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. “My politics were leftist and it was one of those rites of passage. You know, if you’re going to be radical left, you have to have that on your visa,” he said of the trip. While in Moscow, he spoke on a Soviet radio station and learned about an ideology which he had praised despite what he calls his incomplete understanding.

Cambridge admitted that the Soviet experience softened his radicalism.

“There were many little things that you noticed — the minute you arrived in Moscow your passport was forfeited,” he said. “Then young people approached you expressing their desire to have your blue jeans. They would do or trade anything to get a pair of blue jean. That’s when you began to see the fallacy of the system that committed members of the opposition to prisons or asylums because they opposed what was going on in their country. You knew this method of governing would come to an end.”

After returning to the US, Cambridge applied for a summer job at the World Bank, which ended up as a career with a salary that would have made him a millionaire back in Guyana.

“You can only work on those institutions from the inside,” he said, rationalizing his employment at what one of his Bologna professors called “the capitalist institution par excellence.”

He may not have upended the mechanisms of global capitalism, but the Bank hasn’t mainstreamed his political ethos.

“Those views don’t change; in fact, they get reinforced when you’re in this business, because whatever part of the world you go to offends your sensibility when you see the disparities that exists,” he said. “It devastates you and you get angry and you want to do something about it. And through the work of the World Bank, there’s an opportunity to try and do something about it.”

As an economist at the Bank, Cambridge has witnessed abject poverty and hardship in nearly every part of the world, from Calcutta to Somalia. There have been times when he was overwhelmed with what he witnessed, making it difficult to continue with a project. He mentions an indelible experience he had working in Bangladesh.

“One day I saw a crowd in the street and there was a naked woman who was in the street banging on these buses and nobody was protecting her. She clearly was mentally challenged, but I thought when a society gets to that point that nobody would protect her, I just … I couldn’t go back.”

But it hasn’t stymied his drive.

“My passion for development came when I actually started doing development work.”