When Sheridan Johnson was choosing a college, she said her parents assured her there would be a place for her to find community.

Johnson has Navajo, Cherokee and Lumbee heritage and grew up in North Carolina, where she said many community members live. However, at American University, she said she discovered that finding a community was more difficult than her parents made it sound.

“It’s like AU didn’t expect to have Native students,” Johnson said. “So they were like, ‘Why do we need to have a Native space, if we don’t have any?’”

The Indigenous population at the university was under 1% in 2020, according to Data USA, which tracks college statistics. American Indians and Alaska Natives, as they are listed in the census, make up 1.3% of the U.S. population, according to 2020 U.S. Census Bureau data.

AU students worked to create more Indigenous spaces on campus this year by hosting events and engaging with the university about Indigenous inclusion in class curricula, recruitment and land acknowledgment statements.

The land AU currently owns used to be inhabited by Indigenous people. AU and most of Washington are located on Nacotchtank (Anacostan) and Piscataway land, according to a map created by Native Land Digital, a Canadian-based nonprofit focused on Indigenous ways of knowing. This has led Indigenous students to seek more affinity spaces on campus.

Johnson is the director of the Indigenous Initiative on campus, which serves as a programming hub for Indigenous clubs and activities, and founded the Native American/Indigenous Student Association, or NAISA, an affinity group that started in the Spring 2023 semester.

“I’m hoping for at least my affinity group to just provide a space for people coming or who are already here,” Johnson said.

Johnson also said that some efforts to include Indigenous topics in first-year courses like AU Experience, or AUx, have been effective but said there are still opportunities to learn about indigeneity in majors like American Studies. As director of the Indigenous Initiative, Johnson is involved in coordinating events focused on Indigenous topics.

The Indigenous Initiative is part of the School of International Service’s Undergraduate Council. Olivia Olson, who uses she/they pronouns, founded the initiative after seeing a campus-wide gap in programming centered around Indigenous students. Olson then said they learned from other initiatives, like Students for Change, to create and operate the initiative.

Johnson is the current director of the initiative and Olson was the director for the Fall 2022 semester.

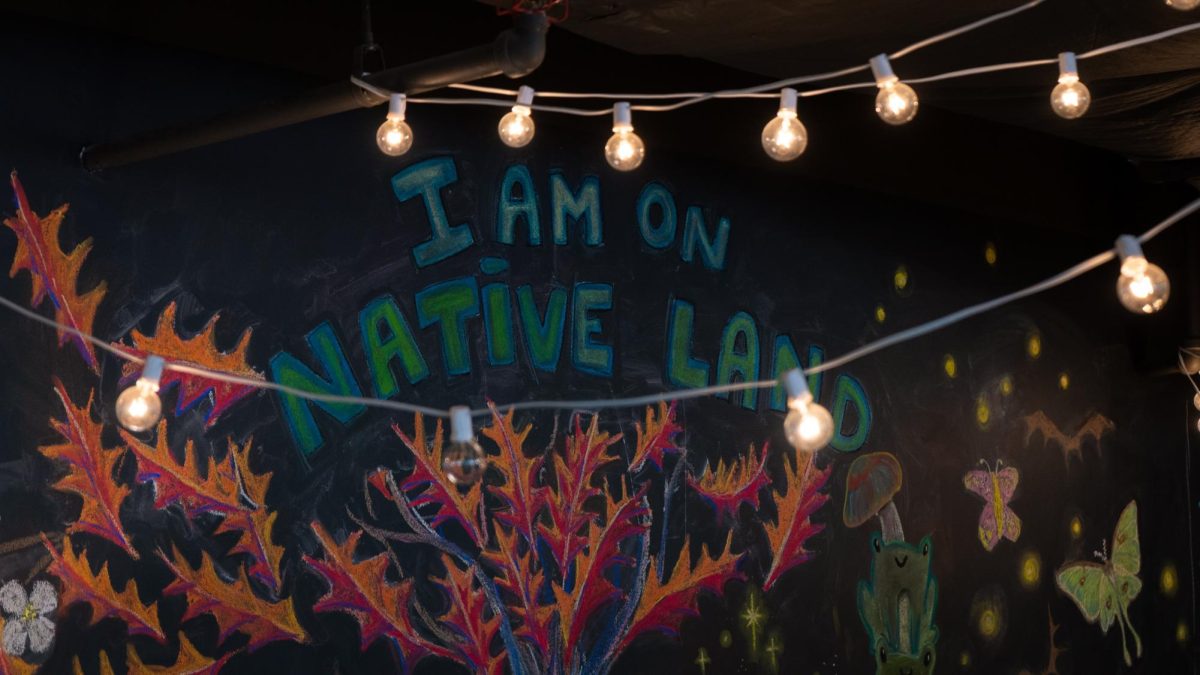

The Indigenous Initiative hosted events during the Fall 2022 semester, including the unveiling of the “I Am On Native Land” mural at The Bridge cafe, an on-campus coffee shop. The initiative also hosted a Settler-Colonial Healing Circle to discuss frustrations members have about living under settler-colonial regimes, according to the organization’s Instagram.

Olson said that some majors, like political science, can be white-dominated and should do more to include other scholars who use a decolonial lens. Olson’s major is within the School of International Service.

“Specifically with international service, I feel like it’s important to recognize positionality, different histories based on which place you’re working with and, with professors, an awareness of how traumatizing some of these teachings can be for Indigenous students specifically,” Olson said.

Students pursuing other degrees also felt that indigeneity was undermined in the classroom. Bruce Leal, the president of the Native American Law Students Association at the Washington College of Law, is Native Hawaiian and originally from Guam. In 2020, U.S. Census Bureau data counted more than half of Guam’s population as part of its “Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander” category. That includes a group of more than 50,000 indigenous persons known as Chamorro.

Leal said his law courses tend to ignore subjects like tribal law to focus on state and federal law.

“It’s entirely incorrect and inappropriate to prioritize Indigenous indigeneity while completely dismissing Indigenous sovereignty,” Leal said.

Law professor Ezra Rosser has taught Federal Indian Law at AU Washington College of Law, WCL, and joined the department in 2006. Rosser said he has seen several students become inspired by Federal Indian Law and incorporate it into their careers.

“The law doesn’t apply in the same way as it does in other areas of law,” Rosser said. “Understanding that there is a third sovereign, I think makes it a valuable class for students.”

Rosser said that other schools closer to places with large Indigenous populations are likely to attract Native American students. Rosser said that although there aren’t many Native American students at the school, other WCL students are still interested in Indigenous law topics.

“I do think that a school like American, in order to attract Native students, has to not be a passive, but has to be an active admissions office,” Rosser said. “And I know we are, admissions officers go to locations that are serving underrepresented groups already. And trying to reach those groups is a challenge.”

Amanda Taylor, the assistant vice president of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at AU, said that recruitment has been a topic she has discussed with others within the university.

“When I think about recruitment I think about students, faculty and staff actually as all sorts of key contributors to our community,” Taylor said. “So that’s essential, we have certainly been in conversations with our admissions, our undergrad admissions team around that.”

On Nov. 14, 2022, AU hosted the Summit on Fostering Indigenous Spaces, which aimed to address issues related to curriculum development, campus culture and land acknowledgment statements.

Taylor said she attended the event and that the summit was meant to gather broader opinions on topics like land acknowledgment. She also used the summit to clarify some of the university’s questions.

“We also talked about if we were to do a land acknowledgment, what are you actually acknowledging, right?” Taylor said. “Is it the land? Is it the people? Is it the treaties that have governed the land?”

After the summit, Taylor said people had differing opinions and that part of her plans for the Spring 2023 semester involve reaching back out to the faculty, staff and students who participated in the summit to try and act on the issues discussed.

In an April 7 email, Taylor said the group planned to meet again the week of April 10 to discuss takeaways from the summit.

Emily Bass said she helped to organize the summit when she was president of Student Advocates for Native Communities, an organization that is no longer active. She said that the previous efforts of the university were also a topic of discussion.

Bass said that AU has previously had programs that supported Indigenous students, like the Washington Internships for Native Students program. WINS provided internships and learning opportunities for Indigenous people but closed due to funding issues in late 2016, according to the program’s archived website.

“In the past, we’ve had stuff like WINS, and AU used to hold an annual powwow that brought tribes from all around the region and when WINS went away, that went away,” Bass said. “So AU definitely has the capacity for it. I think it’s just funding now.”

Bass said she has pushed AU to participate more actively in Indigenous issues. She also participated in the Sovereignty and Stewardship Alternative Break program, which wrote an open letter published in The Eagle in March 2022. Bass said the letter partially inspired the summit.

The letter asked for a land acknowledgment from the university and for them to pay the Piscataway Conoy tribe for their land use.

“The reason we included it is because it was one of the only asks that the Piscataway Conoy tribe, and specifically the Cedarville band, has as a constant ask from settlers,” Bass said.

While the university does not have a land acknowledgment statement, the School of Education published a statement in the Summer of 2020 that said the school is on the traditional territory of Nacotchtank, Anacostan and Piscataway land.

Cheryl Holcomb-McCoy, the dean of the School of Education, said in an interview that she worked to develop the statement after attending a conference with a land acknowledgment.

“We want to acknowledge that this is a part of our history and a commitment to decolonize our thoughts and decolonize our curriculum,” Holcomb-McCoy said.

Holcomb-McCoy also said it is important to be anti-racist and inclusive through the school’s actions to avoid being performative.

“That’s why we need to be intentional about our admissions of students from diverse groups, particularly Indigenous people, that we acknowledge the history in our classes and our curriculum,” Holcomb-McCoy said. “It should come up. It should be taught.”

Johnson said she plans to advocate for making AU a more friendly place for Native students, whether through NAISA, the Indigenous Initiative or communication with administrators.

“That’s what I’m trying to bring and I hope it comes to at least half of what I expect,” Johnson said. “Because I just want for the future to be, like AU to be, an inclusive space for Natives who want to come here.”