Katherine Greenstein is used to being sick.

They’ve been chronically ill their whole life and say they’re well acquainted with immune-related health issues. They’re a frequent visitor to their urgent care for upper respiratory conditions and are among the few who have received the pneumonia vaccine, which is only given out to adults under 65 years old if they experience a medical condition that puts them at risk, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, being sick took on a new meaning for Greenstein when the COVID-19 pandemic started.

“I remember hearing a kid who couldn’t have been older than 15 or 16 say, ‘Oh, it’s only the sick and elderly who are going to die,’” Greenstein said. “I had never fully had that hit me yet where I was like, ‘Oh my god, I’m the sick.’”

Three years after the pandemic’s start, Greenstein, now a junior, is one of the many immunocompromised American University students who say the coronavirus is an ongoing concern for them.

Izzy Scholes-Young, the treasurer of AU’s Disabled Student Union, had COVID-19 for the second time at the start of 2023. Scholes-Young, who is on immunosuppressant medication to treat their autoimmune disorder, said that while the risks are lower than in 2020, this does not mean the pandemic is over.

“I think that saying the pandemic is over is saying like the flu is over,” Scholes-Young said. “I think that we weren’t effective at controlling it, and so it has become endemic.”

While infection rates have decreased in the past year, COVID-19 was the sixth leading cause of death in the U.S. in January 2023, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report. Since the start of the pandemic, there have been significant changes in how the pandemic is handled on a federal and local level. The Biden administration announced in January that it plans to allow COVID-19’s public health emergency status to expire on May 11, and D.C. ended its free test distribution program in February, according to a statement from the Executive Office of the President.

AU followed similar protocols to the White House. The start of the 2022-2023 school year marked major shifts in the university’s handling of the pandemic. AU stopped conducting surveillance testing of the community and switched to voluntary testing, expecting students would test should they experience symptoms or come in contact with someone who tests positive, according to a university memorandum released August 2022.

Previously, if students living on campus tested positive, they were relocated to a local hotel to isolate. During the 2022 to 2023 school year, students are expected to isolate themselves in their dorm rooms, according to the university’s COVID-19 guide for residential students. The guide explained that while isolating, students are expected to wear masks inside and outside their rooms but can leave to pick up food, do laundry and use communal bathrooms. Roommates of those sick with COVID-19 are not required to isolate but are encouraged to mask and are unable to request a temporary room change to avoid possible exposure, according to the guide.

According to a university memorandum, AU also started the fall 2022 semester with a masking requirement inside classrooms, but it dropped its mandate in September. The decision was made based on community feedback and the university’s other ongoing safety efforts, including a reported 98% vaccination rate and on-campus PCR testing, according to the memorandum.

AU COVID-19 precautions continue to decrease. The university announced in an email to the AU community on March 7 that it would no longer require COVID-19 vaccinations or booster shots after the Spring 2023 semester ends. They will also stop offering PCR tests on campus, and rapid tests will be available for free.

Scholes-Young said they were frustrated by the easing of COVID-19 precautions on all levels and felt that it made it more difficult for individuals to take protective measures.

“We encourage our faculty and staff members to work and support our students as we collectively navigate the endemic phase,” said Jasmine Pelaez, the internal communication manager for the Office of Communications and Marketing. Pelaez cited the university’s disability accommodation process, which allows students to request academic and housing accommodations based on their needs.

Scholes-Young said that even with accommodations, immunocompromised students might still feel pressure to ignore their needs. Scholes-Young has flexible attendance accommodations in order to allow them enough time to recover from illness fully, but they said some professors still expect them to meet attendance requirements.

Because of the pressure, ScholesYoung said they weren’t surprised to see so many students, immunocompromised or otherwise, drop protective measures. In some cases, they said they even felt the pressure to unmask.

“Community pressure is on the institutions who have made it a lot more inconvenient and a lot less accessible to do the sorts of things that keep other people safe,” Scholes-Young said. “I don’t fault individuals who feel like, ‘The pandemic is over and I don’t need to wear a mask anymore,’ because that’s the message that you’re getting from all levels.”

Sophomore Beck Hassen felt that policy changes were motivated by public opinion instead of the other way around. Hassen said he felt like the university maintained mask mandates because students were willing to wear masks rather than because it was necessary based on the numbers.

“I don’t think it’s much less of a threat than it was a year ago,” Hassen said. “I just think public opinion changed a lot.”

Hassen said he feels safe to unmask because he feels that new treatments and testing options have made it so that he and the people he’s around wouldn’t be severely effected by COVID-19.

“I realized that the disease wouldn’t really affect me that bad if I got it, nor anybody in my family or anybody that I was around,” Hassen said. “For me that was worth forgoing the inconvenience of having to wear one all the time.”

Although some students may feel safe to unmask, others, like Caroline Arnette, felt that students should be keeping in mind the safety of everyone. Arnette, a junior studying public health who is immunocompromised, said the lack of masking among the student body was frustrating and represented a mismatch in the community’s values and actions.

“Don’t get me wrong, I believe in a community of care,” Arnette said. “But it’s ironic when you, a relatively privileged, abled person, in general, you talk about a community of care, while sneezing into your elbow without a mask on, and I’m sitting next to you.”

Arnette said she felt like other students don’t consider their actions’ impact on the disabled and immunocompromised students around them.

“I don’t assume that everyone who celebrated the end of masking is ableist and wants me to get sick and wants me to die,” Arnette said. “I don’t believe that. I think they don’t even consider me in the equation. And that also hurts.”

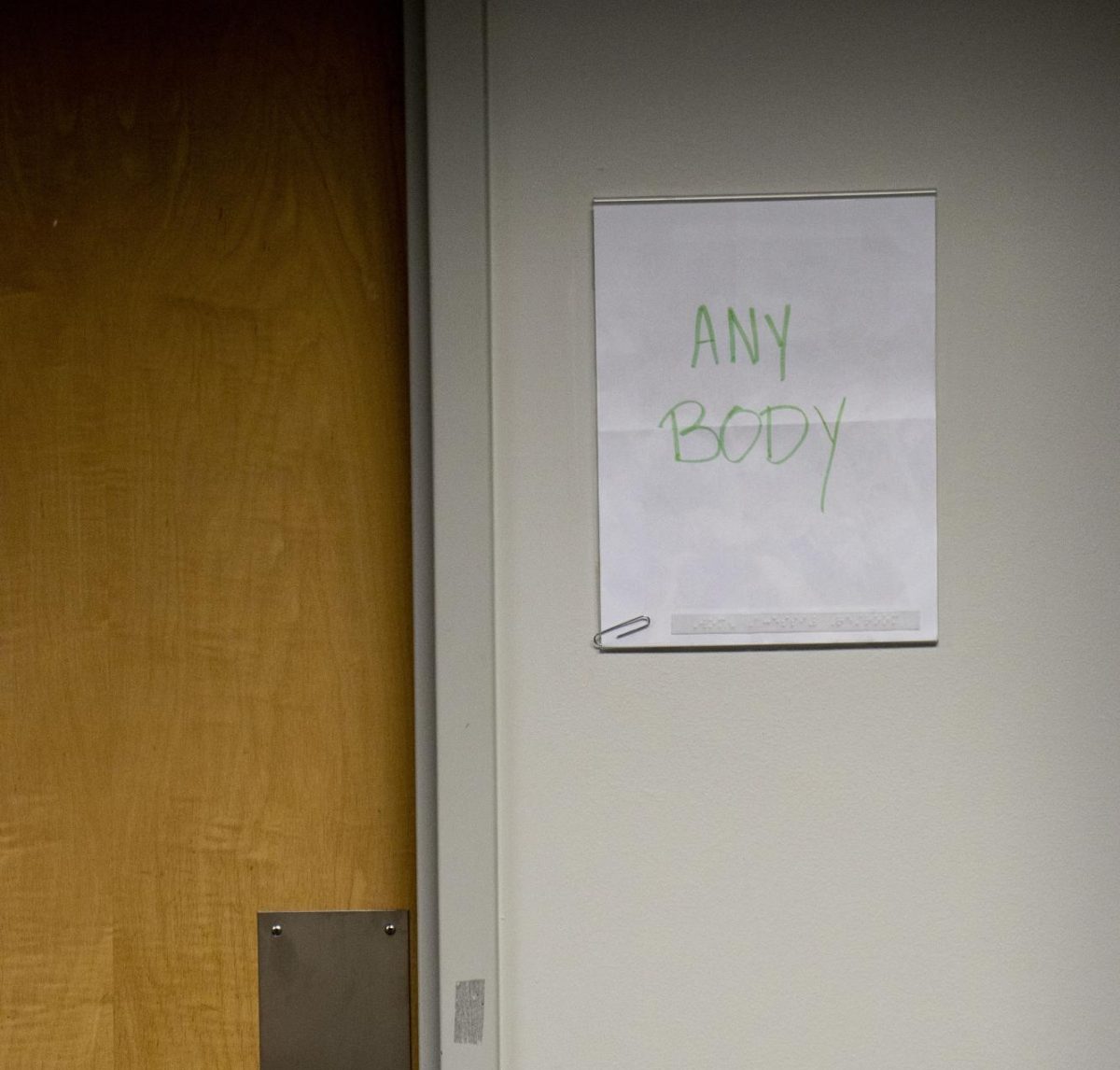

Henry Jeanneret, president of the Disabled Student Union, said that students could be more thoughtful when approaching COVID-19 precautions, including masking.

“It’s a way to show disabled people like, ‘Hey, I recognize you and I value your life,’” Jeanneret said. “’I don’t see you as disposable.’”

Jeanneret, who is not immunocompromised, said that other students should be listening to disabled students and taking steps to protect them, even when it’s inconvenient. Jeanneret doesn’t like wearing masks because they trigger his sensory issues, but he said he wears one anyway to keep his immunocompromised friends safe.

“The big thing is, I can take a break from wearing a mask,” Jeanneret said. “My friends can’t take a break from being immunocompromised.”

As for Greenstein, they’re trying to remain optimistic. They spent the past school year abroad in Northern Ireland to escape a version of AU they described as “almost war-torn” from COVID-19 debates. Greenstein said they are hopeful that for their senior year, they will return to a community at AU that works together to keep at-risk students safe. But they said they’re worried AU hasn’t changed enough.

“I want to come back to somewhere that feels as good as it did when I toured as a high school junior and fell in love,” Greenstein said. “I want to come back to the same place I fell in love with, and I just worry that I’m going to come back and that love is gone.”