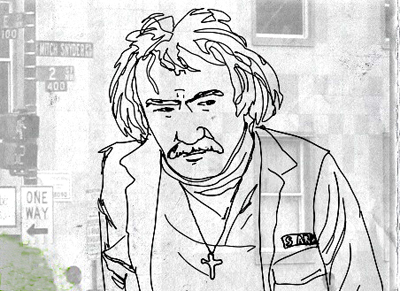

Mitch Snyder's Ghost

November 11, 2009

CCNV, founded as an antiwar group in the 1970s, scored a victory for D.C. homeless in 1984. The idealistic organization convinced Ronald Reagan to let homeless people occupy an abandoned federal building for the winter of 1984.

And when the winter season formally ended on April 1, CCNV and shelter residents conducted takeovers of federal offices, disrupted Congress, and fasted for 51 days. Two days before the 1984 elections, Reagan turned over the building for good.

CCNV’s battle against homelessness was multifaceted. Activists collected 35,000 signatures in order to put a proposal on all District ballots. In 1984, “Initiative 17” passed with an unprecedented 85% approval, creating a legally-binding mandate that D.C. government must provide emergency shelter to any and all of its residents.

In response, then-Mayor Marion Barry’s administration scrambled to find shelter for hundreds of men and women living on the streets, gathering them in vans and rushing them to makeshift converted shelters.

Next, CCNV brought suit against the Barry administration for its inadequate maintenance of the emergency shelters. A judge fined the government $5,000 for every violation—leaking roofs, broken windows, lack of bathrooms, hot water, clean sheets, or resident storage space. Between 1985 and 1987, the Barry regime was forced to fork over $4 million in fines. The money paid for massive increases in the services provided to the homeless.

***

At the heart of CCNV’s movement was Mitch Snyder. Born in Brooklyn, Snyder struggled to find direction as a child, and fell into petty crime. When he was in his mid-twenties, he was arrested for stealing a car. In jail, he met Philip and Daniel Berrigan, radical Catholic priests imprisoned for their civil disobedience against the Vietnam War. Snyder adopted their religious philosophy and radical dedication, joining them in fasts against the war and the mistreatment of fellow prisoners.

Snyder’s passion became clear when his family grew concerned about his fasting. In a note to his mother from prison, Snyder wrote: “I would like you to be proud that your son believes strongly enough in justice, to oppose injustice with all the strength at his disposal.” After being released, Snyder moved to D.C. and immersed himself in a community of committed activists.

“Mitch was one of the most dedicated people, the most creative, thoughtful, confrontational, manically insane human beings I have ever met. He had an uncanny ability to understand that when things were wrong, you need to stand up and say what needs to be said to correct the injustice,” said Brian Anders, a former member of CCNV who worked with Snyder at CCNV in the 1980s.

“He was willing to as far, if not further, than anyone else, so that injustice could be stopped.”

Snyder often fasted in support of his causes. For weeks, he stood up in congregation at the Holy Trinity Parish in Georgetown to protest their expensive renovations while homeless people lacked basic services. He organized public funerals for people who froze to death on the street. His acts often attracted national media attention—he was the subject of an Oscar-nominated documentary as well as Martin Sheen’s lead role in a 1986 movie.

Snyder and CCNV’s crown jewel was the Federal City Shelter. By wrestling the building away from Reagan, the group tackled Goliath. They were able to go further, transforming the abandoned building into an inspiring, cooperative community of homeless people and activists.

Anders portrays CCNV in the 1980s as “a multiglot of people learning from each other, living together.” CCNV prided itself on its communal meals of staff and residents, its twice-weekly spiritual meetings, and its system of internal governance that gave its homeless residents an active role.

He describes a community where people who had never left D.C. were able to meet people from all over the world. “We were able to learn from each others’ experiences, living together in a harmonious way,” he says. “We had a common enemy—the system that disenfranchised us, kept us poor, kept us impoverished.”

***

“The spirit of that died after Mitch killed himself,” Anders said.

Snyder was found dead in his room at CCNV on July 6, 1990. According to a note found by police, he hung himself out of frustration with his romance with partner Carol Fennelly.

Shortly after, the atmosphere at CCNV began to change. The list of rules grew longer. Time limits were placed on resident stays. “The spirit of the community fell apart, and core people left. CCNV and the shelter became an institution,” says Anders. The staff began to pursue their own power, and grow corrupt with it, he said. The atmosphere at CCNV became oppressive. “The shelter has deteriorated to a cruel, unhealthy environment.”

Mitch Snyder and the core CCNV activists of his time created a true communion with the homeless people they were advocating for. At CCNV today, this cooperative, compassionate approach is missing.

An AU graduate who volunteered at the shelter tells the story of one former CCNV resident she remembers meeting. “[The woman] was blind and in a wheelchair, and the staff didn’t like her because she was always asking questions of them and demanding better treatment.”

One night, CCNV had a fire drill. “When the fire alarm went off, she was left upstairs in her wheelchair, and when other residents tried to help her down, the staff chastised them and told others not to help her.” Left alone in the building as the alarms blared, and uninformed that there was no actual fire, she tried to escape on her own. She stumbled, fell down the stairs, and couldn’t get up. She simply laid there, assuming her fiery death was imminent, until a shelter staffer found her when the drill was over.

“CCNV today lacks compassion,” says Anders.

Residents say that they hear the ghost of Mitch Snyder wandering the halls at night.

Since 1990, the city has closed several shelters, booting homeless men and women into the street—despite fierce opposition from activists and advocates. Initiative 17 has been overturned. And bold efforts to help the homeless—protests, occupations, and pleas—have attracted little media attention.

Today, the District is being overrun by gentrification. The city is giving away public property (including former homeless shelters) to real estate developers, public housing projects are being demolished, poor people are being forced out by rising rents, and rich people are moving in. The homeless and their allies often feel overpowered, seeing the tide of rich white newcomers flow into the city.

Anders issues a challenge to those who doubt the ability for ordinary people to enact extraordinary change. “People always say that we need another Mitch Snyder to come and save us,” he said. “We don’t need another Mitch because all of us can be Mitch Snyder. We need to quit looking outside of ourselves for the hero.”

Mitch Snyder was an selfless, spirited, and laudable individual, but CCNV was able to combat unjust economic practices with their intrepid dedicated activists. “I think Mitch would be embarrassed if he knew people were still talking about him twenty years after his suicide, because he knew he was nothing without the community,” Anders said.

“We need everyday, regular people, not another Mitch Snyder. We all need to be Gandhi, be Malcolm X, be Mitch Snyder. If we could do that, it wouldn’t be perfect or Utopian, but it would be better than doing nothing.”