The “rise up.” photo exhibit brought the Black Lives Matter protests below ground

Dupont Underground’s in-person and online exhibit captured the vitality and tumult of Washington’s 2020 Black Lives protests in photographs.

November 1, 2020

Underneath Washington D.C.’s Dupont Circle lies 15,000 square feet of underground space occupied by Dupont Underground, a nonprofit community arts organization. The front desk’s quiet music and the murmurs of visitors’ conversations echoed off curved walls in the tunnel-like space, mingling with sirens from above.

The organization’s current exhibit, “rise up. for the people, for the future,” featured photography capturing this year’s Black Lives Matter demonstrations in Washington. The in-person exhibit closed Nov. 1, though the online version will remain available until Jan. 12. The collection ran on Fridays and weekends throughout October and, according to Dupont Underground’s front desk manager, welcomed around 60 masked visitors each day it was open.

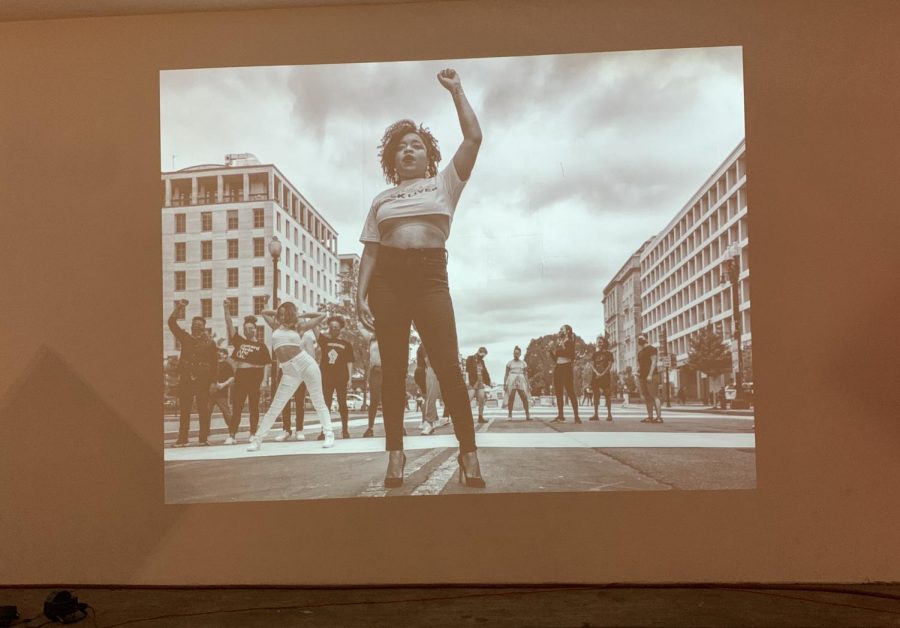

Across from a brightly-colored permanent mural that spans the length of the space, projectors threw 10-foot by 10-foot images of this year’s Black Lives Matter protests onto the wall behind old trolley tracks. Bios of the photographers were displayed next to the pictures.

On the ground below the photos stood bright orange road signs, glowing in the shadows between the projections.

“WATCH FOR BLACK LIVES,” read the first one, followed by, “WRONG WAY, RACIAL DIVIDE.”

The “rise up.” exhibit’s curator, Shedrick Pelt, was inspired by the Washington community and its role in the nationwide movement for racial justice. Black Lives Matter protests occurred almost daily throughout Washington from May through September.

“One of the things that really stuck out for me was how important D.C. was to the conversation,” said Pelt, who also serves as Dupont Underground’s photographer and social media director. “On the nightly news, you would see Seattle, you would see Portland, you’d see New York, and you’d see D.C. right there along with them with the coverage of the nationwide uprising.”

According to a report on the Metropolitan Police Department website, 561 people have been arrested in connection to protests in Washington since May. Smaller, locally-focused demonstrations have continued, including an Oct. 27 protest demanding body camera footage after a man died in a moped crash during a police chase.

“As a photojournalist, I had been out documenting, embedding with these groups that were protesting,” Pelt said. “Once you connect with them, and you walk with them, and you march with them, you realize this is a very well-organized, committed situation.”

Pelt said he wanted the collection to highlight the stories of Washington’s demonstrators. He recalled one woman who told him she had protested in the street for 19 days straight, and said that he wanted the exhibit to showcase protestors’ dedication to their cause.

He also said he wanted the exhibition to serve as an opportunity for local photographers, both professional and amateur, to display their work for a wider audience.

“When the activists and organizers and protesters, when they get tear-gassed, the photographers are right there beside them getting tear-gassed. So they’re part of the story too,” he said. “We don’t have any Washington Post photographers, we don’t have any Pulitzer Prize winner photographers, we just have your everyday citizen that’s out there documenting their neighborhood, their people, their city.”

Artists were invited to submit their photos of Washington’s Black Lives Matter protests throughout September, and a panel of five “jurors,” who Pelt picked out, chose the pictures. Pelt also created the criteria for judging the photos, which he said in an email included the photos’ conveyance of detail, emotion, action, conflict and message. Pelt also created the marketing graphics and web pages to advertise the project.

“As a journalist, as a Black man, I took this opportunity very personal,” Pelt said. “I did all these things to take ownership of it because I just felt like I needed to, based on my connection to the movement.”

Dupont Underground is run primarily by nine staff members, who work largely on a volunteer basis. The “rise up.” exhibit required involvement from everyone there, and Pelt is not the only one with a personal connection to the exhibit.

“We have an exhibition that actually is going to highlight my life, pretty much, because I’ve been Black all my life and I’ve been going through the trials and tribulations of any typical African American,” Ken Brown, Dupont Underground’s front desk manager, said. “I’m really happy that Dupont Underground is a hub for an actual exhibition of this magnitude, and I’m happy to be a part of it.”

Brown described the response from the public as “total positivity.” But he also said that opening up in person was not an easy decision during the coronavirus pandemic. Free masks, hand sanitizer stations and arrows directing visitors’ foot traffic served as reminders that police brutality is not the only threat confronting the Washington community right now. In accordance with the city’s protocols, only 60 people can occupy the space at a time.

“It took a little while, but we’re back open,” Brown said during the exhibit’s third weekend. “This is a space where we have live performances, comedy shows, a lot of interaction — a lot of closeness. So, you know, for us to actually be one of the few places in DC to go is a big deal.”

For students living outside the DMV or Washington residents who did not see the exhibit in person, the online “rise up.” gallery offers a way to connect with the Washington community. The space at Dupont added elements to the collection, such as orange road signs, but the digital version has its own features. While the in-person projections switched between the images and the photographers’ bios, the online gallery allows viewers to choose how long they sit with each photo.

The online version does not consist of a long list of photos to scroll or click through, nor does it group them into neat, categorized folders. Rather, it features an interactive, 3D gallery through which a viewer can digitally walk.

“Not only was it important that we do some type of virtual aspect, the virtual aspect needs to also represent the photos properly,” Pelt said. “It just couldn’t be some janky situation. It needed somewhere that really paid homage to the photos, to the photography, and to the message behind the photos.”

The photos depict many individual scenes from the mass protests. One photo by artist Robb Hill shows a Black woman in a rainbow tye-dyed BLM t-shirt waving a bubble wand on top of the bright yellow lettering of Black Lives Matter plaza. Behind her, a young family takes a group photo in front of a life-size picture of the late Congressman John Lewis.

In a photo by Navy veteran Tina Staffieri, two police officers in riot gear hold a person in a sunflower-patterned shirt to the ground and cuff their hands behind their back. At least eight other officers, three of them armed with metal batons, stand around them, facing away.

Pelt said that the goal of the gallery is to stay committed to the movement fighting for racial justice, because “we’ve known since Michael Brown and before that…the same things continue to happen.”

“Even in the time of COVID, people are masked up, people are being safe, but people are out here, people are voicing their opinion,” Pelt said. “People are out here every day and it’s like, we’re not giving up. Things aren’t different; things are unfortunately the same, you know? And that’s why we’re doing this.”