The color of wealth: Gentrification’s effects on wealth in DC

Over the years, gentrification has become a household word for thousands of D.C. residents who are unable to afford to live in increasingly expensive, renovated housing and neighborhoods.

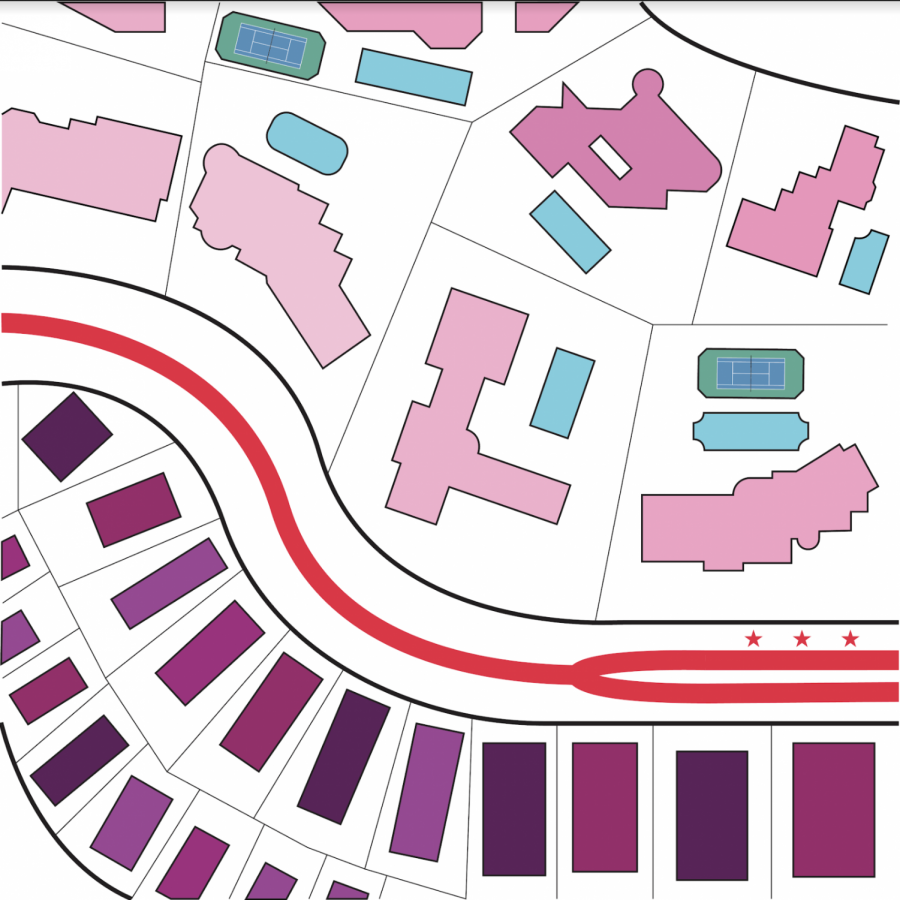

D.C. has the highest percentage of gentrification in the country, according to a 2019 study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. The study found that 41 percent of the district’s eligible neighborhoods have undergone gentrification between 2000 and 2013.

Community leaders are also reacting to the worsening reality of the District. What was once the majority black and middle-income is now increasingly white and wealthy. Dominic Moulden, a resource manager for the non-profit organization, Organize Neighborhood Equity or ONE DC, is one of many that are advocating against this pressing issue.

“People will say illogical things like gentrification is good,” Moulden said. “So I ask people, how is it ever good for people to be removed against their will?”

The idea of residents no longer being able to afford to live in their own communities is nothing new. As an issue that stems back decades, gentrification and D.C.’s wealth gap has only gotten progressively larger over time. This growing divide has become more noticeable when comparing the eight different wards in the District, which have staggering differences in median income.

Ed Lazere, executive director of the D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute, defines gentrification as “a community that is changing when a neighborhood that is largely low-income and often people of color or immigrants where that community has an influx of higher income and often white people.”

While the definition appears clear-cut, its history in Washington, D.C. has been more complex in terms of the influx of new residents versus previous residents. Between the years of 1980 to 2015, there has been a decline of 135,000 African-American residents and an increase in 66,000 white residents in the District, according to a Greater Greater Washington study.

However, in the same time span, there has been a large influx of Hispanic and Asian residents, about 50,000 and 17,000 respectively, in the District. While this may not be an exclusively black and white issue, this does not take away from the longtime residents’ inability to afford to live in their renovated neighborhoods.

Lazere discusses the implications of historical discrimination against communities of color in today’s economic climate based on his policy research at the D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute.

“Our history of cultural and institutional racism has just consistently denied opportunities to black people and other people of color,” Lazere said. “[This has been] resulting in enormous differences in income and wealth and power.”

Certain neighborhoods face even greater changes in population and racial makeup than most. One example is the Shaw neighborhood, which has faced massive decreases in the black resident population. In 1980, Shaw was 78 percent black. However, by 2010, the population decreased to 44 percent, according to NPR.

While the D.C. local government has developed different economic development strategies to try and promote affordable housing for all residents, local organizations have decided to take matters into their own hands. Through active research, hands-on community outreach, and educational training, these organizations are trying to help promote equity and opportunity for all of the District’s residents.

The D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute was established to influence D.C. policy and budget decisions, in the hopes of supporting vulnerable communities in the District and reducing poverty and income inequality as a whole.

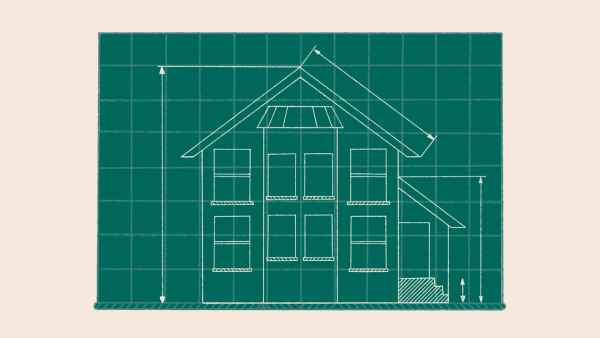

“Home-owning was a key source of acquiring wealth in this country,” said Lazere. “So the fact that black people have been shut out of education and jobs that would allow the ability to buy homes just also means that they don’t have the wealth now to absorb the incredible increases and rising costs around them.”

The effects of discrimination and lack of opportunity for targeted groups in the United States has left an effect on the current generations of D.C. residents and homeowners.

“They’re just vulnerable to rising rent and unable to get a toehold through homeownership now, even if that discrimination isn’t the same level as it was in the past,” said Lazere.

There are numerous other non-profit organizations who are trying to help communities and specific neighborhoods affected the most by this ongoing issue.

ONE DC was founded in 1997 in the hopes of using grassroots and direct action to create and preserve social and economic equity for people of color and lower-income workers in the Shaw district. Moulden works in recruiting interns and volunteers to help raise the necessary funding and materials to continue community organizing within the organization.

“The way to think about this is we are organizing to build power, so people have a right to the city,” said Moulden. “And so we organize through political education and we help focus on associations to exercise their right. We help get buildings as housing cooperatives.”

Moulden also noted how ONE DC is collaborating with two Latinx groups in the District, Dulce Hogar Cleaning and Co-Familia Child Care cooperative. These worker-owned cooperatives also help residents who wanted to start their own businesses, as a result of needing more affordable housing and better job opportunities. This is one solution to the numerous issues regarding re-housing, affordability, and overall wages.

These issues in Wards 7 and 8 do not apply to the entire District, as other areas have residents with higher incomes on average. The current location of American University is in Ward 3, which according to the D.C. Economic Strategy, had a median household income of $122,680 between 2013 and 2017. This is the highest-income ward in the District. In contrast, areas, such as Deanwood in Ward 7, earned a median income of 40,021 and Anacostia, which is in Ward 8, earned a median income of $31,954 in 2017.

Leah Garrett, Vice President of Development and Communications at Community of Hope, works on helping many of these low-income residents in Wards 7 and 8 afford housing and healthcare. These initiatives include hiring residents of their targeted neighborhoods to work for the organization and providing temporary housing for residents who can no longer afford their current homes.

“Our rapid rehousing program provides short-term rental and utility assistance, along with case management, to those families experiencing homelessness”, said Garrett. “We know that within a few months of assistance, our families can become stably housed for years to come.”

By establishing numerous apartment complexes throughout the District, Community of Hope has been able to help residents who can no longer afford to live in their homes.

“Without this program, families in D.C. often enter the overcrowded shelter system,” said Jamey Burden, Vice President of Housing Programs and Policy at Community of Hope.

While the solutions to combat the effects of gentrification will not create change overnight, community leaders are optimistic about what they can accomplish. Moving forward, Moulden hopes to continue on the path towards effective and meaningful action by partnering with other organizations in achieving equity for low-income residents and gives his insight on what needs to be done next.

“Number one: work together more consistently. Number two: we have to leave more discipline, organization and make principal decisions, “ said Moulden. “And then number three: we have to stop the in-fighting. There’s too much competition and fighting amongst organizations and that needs to stop.”

In terms of the local government’s role in preventing the effects of gentrification, Lazere is hopeful the D.C. government has the resources to help their residents.

“The city has all of the tools that we need to preserve existing affordable housing,” Lazere said. “Really the question of the matter is, well, do our policymakers care enough about preserving D.C.’s economic and racial diversity and maintaining and honoring our history has a majority black city?”

Kavi Farr (he/him/his) an SIS junior from Massachusetts who loves graphic design, photography, and taking down the ruling class.

Fun fact: I have...