What to do about gun violence

The auditorium hummed with chatter right before the first meeting of American University’s March For Our Lives chapter on the evening of Wednesday, March 20. The voices of the new chapter’s board members rang in Kerwin Hall’s room 1 as they discussed policy agendas and opportunities for action.

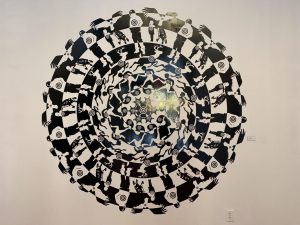

The gallery at the Center for Contemporary Political Art, on the other hand, remained nearly silent in the Walls of Demand exhibition on the morning of March 2. Featuring art focused on gun violence in America, the gallery did seem to encourage idle chatter from the visitors who trickled in from the street outside the Gallery Place/Chinatown metro stop.

The two organizations’ approaches to gun violence activism stand in stark contrast to one another.

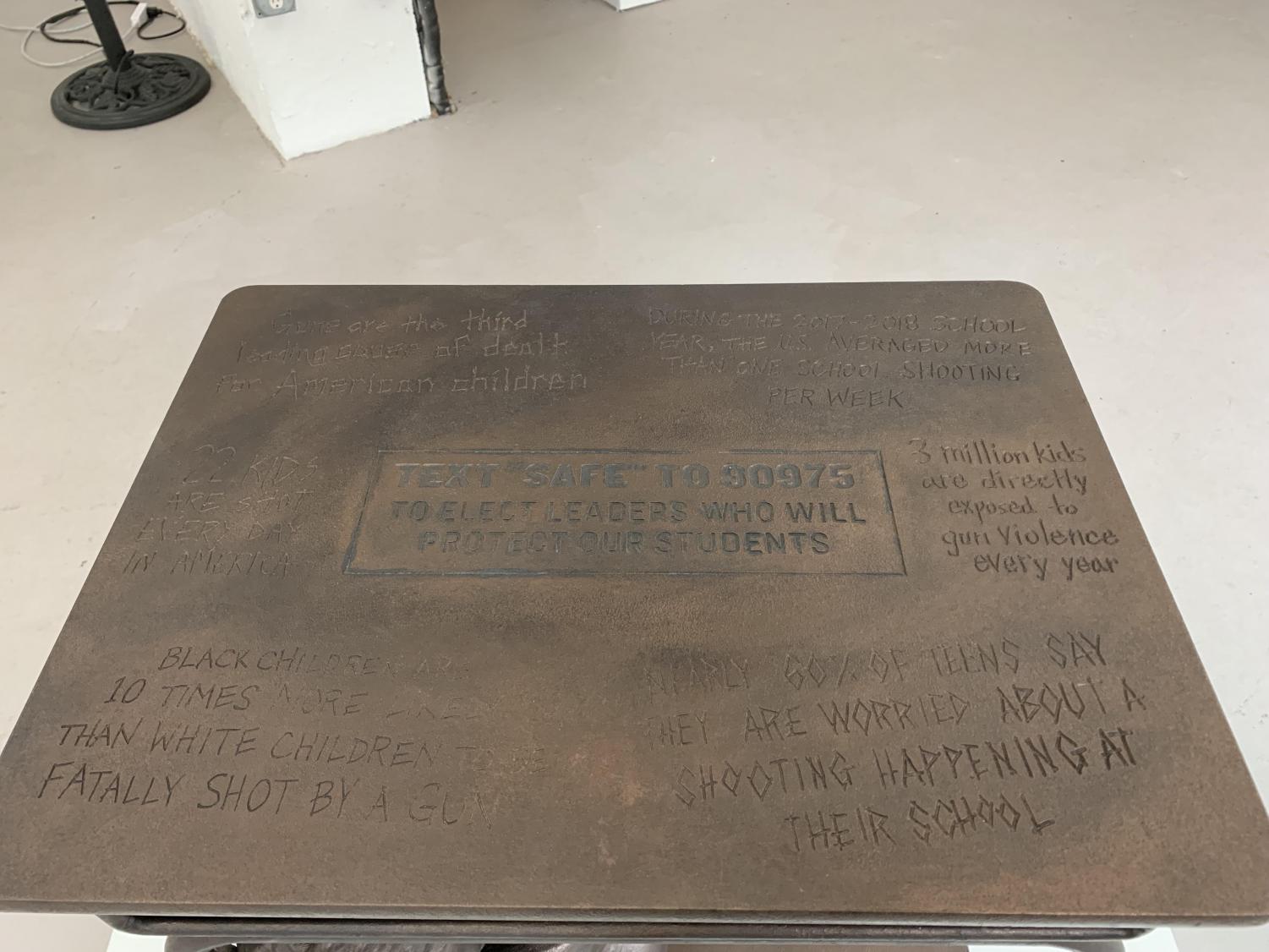

“Where the data and the talking points leave off, the art can reach different people differently,” Robin Strongin, the Center for Contemporary Political Art’s co-founder and chairman, said. “It’s incredibly powerful.”

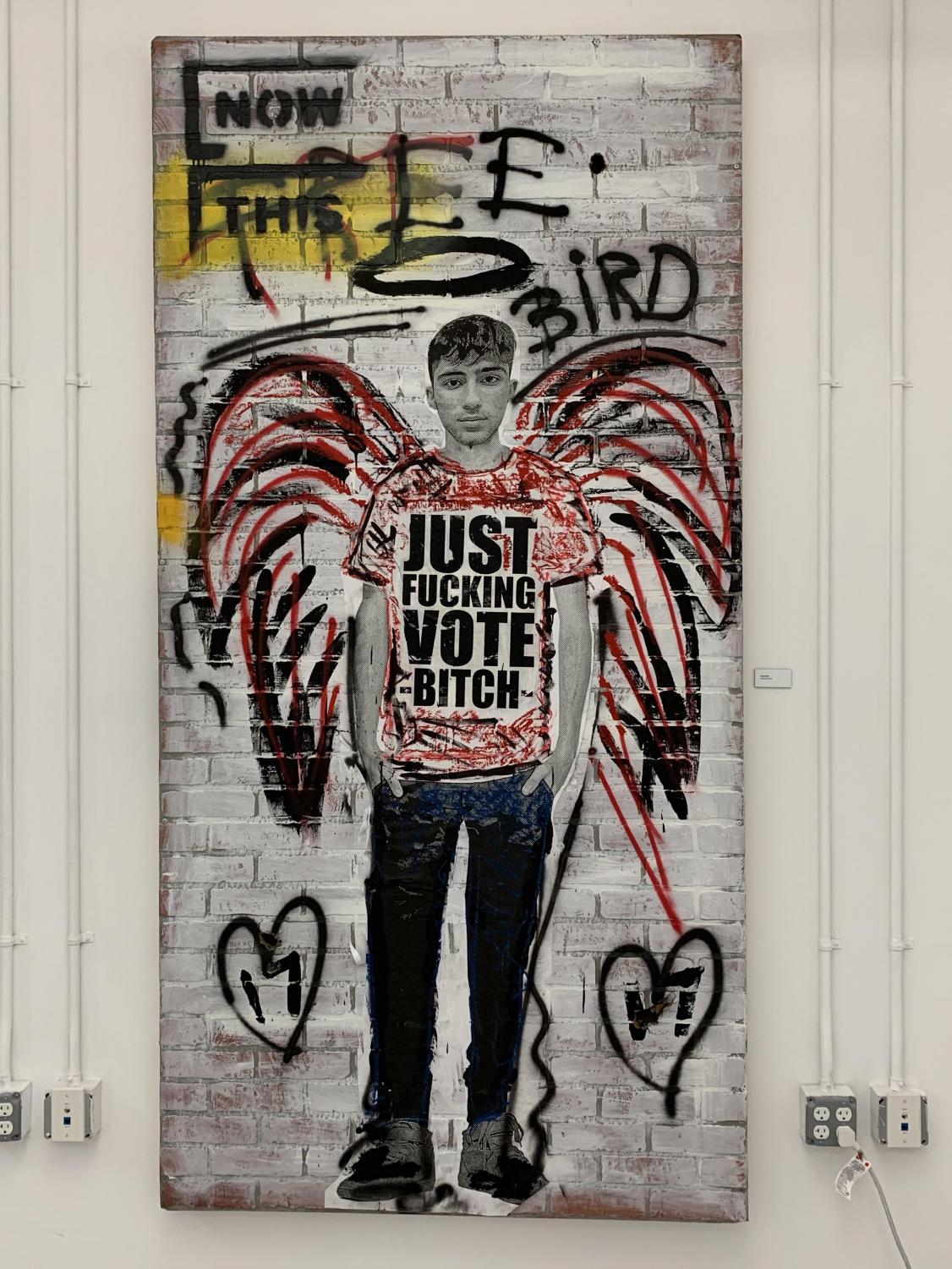

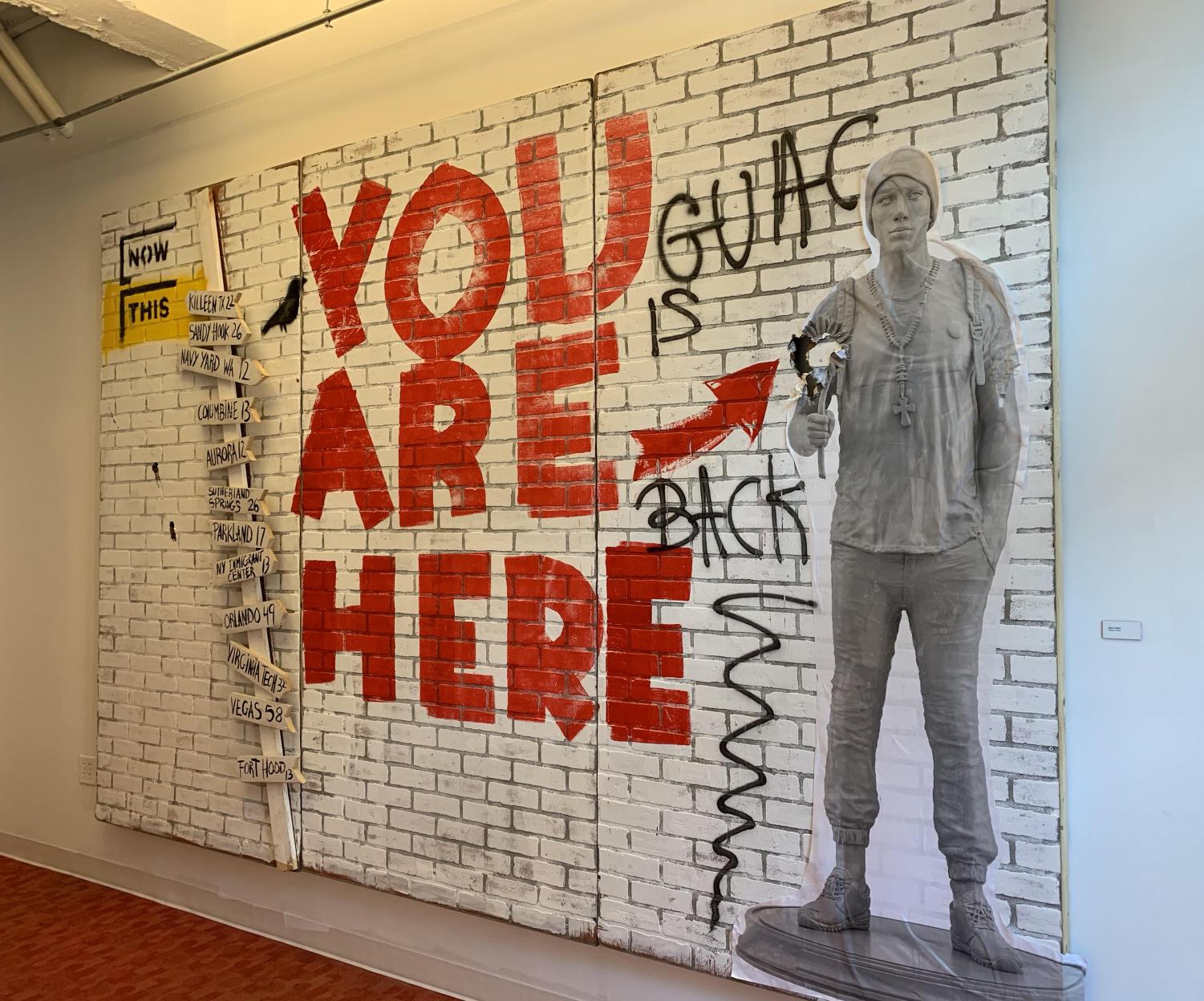

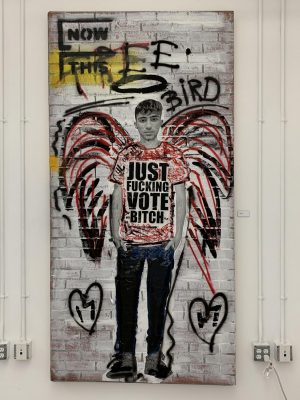

Visitors to the Center walk in the front door to see a piece confronting them with a ghost: Joaquin “Guac” Oliver. He was one of the 17 killed during the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida on Feb. 14, 2018.

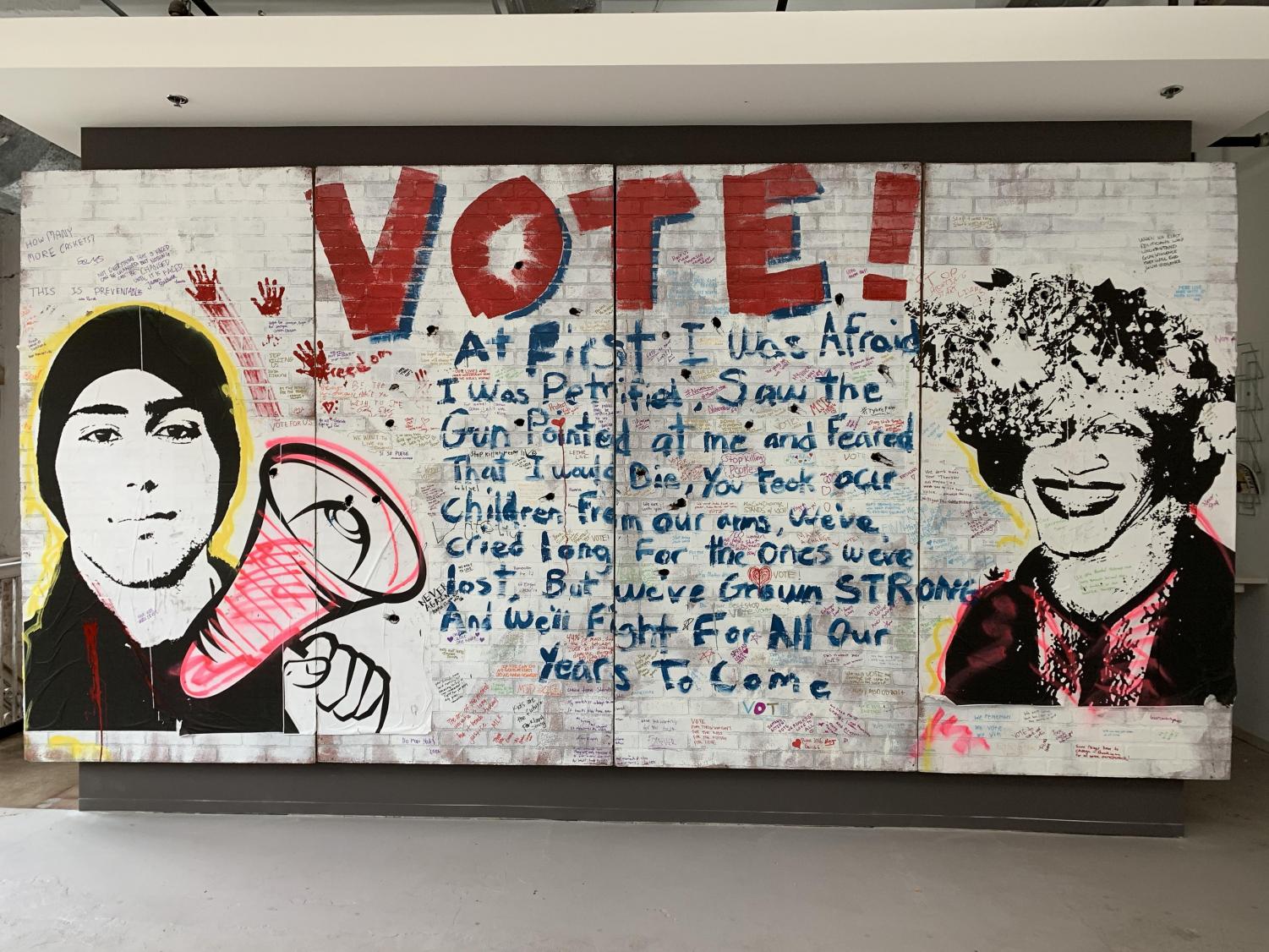

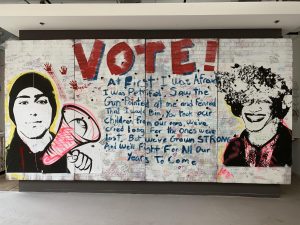

His father, Manny Oliver, created the graffiti-style piece. His contribution to the collection, which includes several street-art murals and one sculpture, intends to give his son a voice. The murals were first created for and set up at various demonstrations for gun violence prevention efforts around the country.

“We decided, Patricia [Manny Oliver’s wife and Joaquin Oliver’s mother] and me, that Joaquin, besides being a victim, that he is, sadly but true, he will be an activist,” Oliver said in a 2018 interview with Democracy Now!. “And this is a way to do that. This is a way to bring the legend of Joaquin, right here, right now, very loud and clear, as one of the kids leading this amazing movement.”

Next to Guac’s portrait, the piece by the door includes a list of other mass shootings and the number of victims. According to Strongin, this sets the stage for visitors to understand both the deep grief and the broad purpose that the Walls of Demand collection intends to convey.

“Both Patricia and Manny felt very strongly that this show, and this effort, was not just about their one son and it was not just about Parkland, that it was about gun violence across the board,” Strongin said. “So while it certainly is about Joaquin, and it is about the Parkland anniversary, and it is about Manny and his work — it’s much bigger than that. And it involves everybody.”

The personal mixes with the political for many involved in gun violence prevention advocacy. Charles Krause, the Center for Contemporary Political Art’s founder and retired foreign affairs correspondent, was shot and witnessed multiple gun deaths while reporting on what became the Jonestown Massacre in Guyana.

Margi Weir, the exhibition’s other main contributing artist, had two friends die in a gunfight over an abandoned house in Detroit, according to the exhibition’s program.

Of the new March for Our Lives (MFOL) AU chapter’s 11 student board members, two spoke of their own experiences with gun violence and three mentioned having friends or family that had experienced gun violence.

Freshmen dominated the chapter’s first meeting, which had 40 total attendees. MFOL AU co-founder Ben Holtzman said that many freshmen may feel such a personal connection to the issue because the Parkland shooting occurred during a majority of those students’ senior year of high school.

“It has not been hard to get people involved in March for Our Lives,” Holtzman said. “I think a lot of our base is coming from the freshman class because they were in it.”

Outreach efforts by DC March for Our Lives chapters at the Parkland students’ speaking event in October yielded an email list with over 300 AU students.

“There’s definitely interest on campus that we’ve been able to tap into, in large part due to the name recognition of what March for Our Lives stands for,” co-founder Adam Frank said. “I think the event was a catalyst, but I think it definitely tapped into something that was already there.”

Both Holtzman and Frank saw the event as a sign to renew their activism efforts; both freshmen had been heavily involved in gun violence prevention movements in high school. After months of work, they gained official recognition as a campus club on Feb. 28. They intend to capitalize on the AU student body’s passion and interests.

“I think a lot of what March for Our Lives AU [Chapter] specifically wants to do is leverage the fact that we’re on one of the most politically active campuses in the country,” Frank said. “Knowing that people want to get involved, knowing that people care about the public good, connecting those people to activism opportunities but also acknowledging that they’re going to be the future decision-makers.”

Recognizing that many AU students are driven by these issues, the two see the chapter functioning as a connection between students and opportunities to affect change.

“A big part of what we do will be connecting AU students to this broader movement, to March for Our Lives DC, to protests, to events on the Hill,” Frank said. “We are sort of functioning as the bridge between AU students and the broader movement.”

Similarly, the Center for Contemporary Political Art’s mission “to inspire needed social and political change through the power of art” means they strive to connect artists’ messages with all types of visitors in the capital. Several high-profile Members of Congress attended the Walls of Demand opening night on Feb. 12, including Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL) and Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-CA).

Since then, the Center has seen such interest that they extended the exhibition’s showing to April 14. It was originally planned to close a month earlier.

“One of the things we do here at the Center is trying to engage with different audiences and communities,” Strongin said. “There are some groups that are interested in doing discussions and some other programming, and we want to make sure the art is still available because it’s such a focal point for people to sort of have difficult conversations and use the art as a jumping off point.”

The March for Our Lives AU Chapter founders echoed the sentiment of inclusivity.

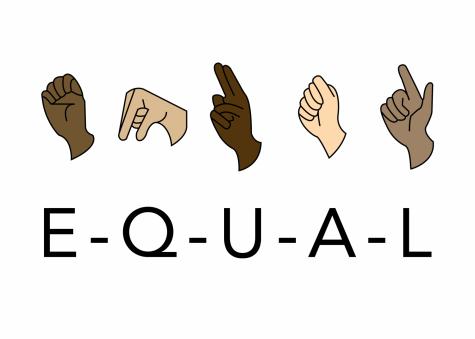

“One of our goals is also intersectionality and making sure that we’re talking about shootings that don’t always get covered by the media,” Holtzman said. “We’re going to be partnering with a lot of organizations that represent voices that aren’t really talked about and that aren’t heard often.”

I'm a freshman double-majoring in journalism and political science. I'm interested in human rights, education inequality, public policy (also, dark chocolate...