Afghan Women Weave Culture: Rugs & Resilience

As the sun set behind the McKinley building, students, professors and various visitors file into the New Media Center. Seated atop tasseled pillows and clad in multicolored clothing, a man and woman begin to play traditional Afghan music to a mesmerized crowd. They are the opening entertainment for a panel discussion about the untold stories of women in Afghanistan.

At the center of this discussion is James Opie, who is not in the New Media Center but across the country. Opie is the creator of the Afghan Rug Project, which he launched in 2006, 36 years after opening his retail rug store in Portland, Ore. Opie, now approaching his 46th year in the Oriental rug business, traveled extensively through the Middle East in the 1970s, increasingly attracted to the beauty of Islamic architecture and a portable feature of this culture: handmade rugs.

“The attraction I felt was a bit like romantic love, but this love focused on something more enormous and historically anchored than individual humans can ever be,” Opie says. “The more I learned, the more I wished to learn.”

At the time, Opie considered Afghanistan to be the “freest and most welcoming nation in the world.” But as the decades passed, unrest erupted in the country after the Soviet Invasion in 1979, disrupting life in the Middle East and Central Asia and uprooting lives.

Poverty and unemployment plagued Afghanistan, forcing millions of people to move to Pakistan or Iran as refugees. It is estimated that more than 1 million civilians were killed in the nine-year conflict, according to journalist Alan Taylor’s article in The Atlantic. Similar to the way unrest in Syria has led to the rise of ISIS, the Taliban preyed on many orphaned Afghan children, brainwashing them became with fundamentalist rhetoric. Today, research from the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University names Afghanistan as the world’s top producer of refugees for the 32nd year in a row, with an additional 700,000 displaced persons struggling to survive within the country’s borders.

Opie argues that stability in Afghanistan is vital for sustaining their nation and culture, but is also essential for maintaining security in other parts of the world. He believes that if Afghanistan falls to destructive forces like ISIS, the entire region will remain uncontrollable for decades to come.

“One challenge, clearer now than it was a decade ago, is that our government can never spend enough in Afghanistan to make a real difference,” Opie says. “The difference needed can only come through more reliable patterns of exchange, exchanges between homes and families in Afghanistan to homes and families here.”

And so instead of donating money, Opie created the Afghan Rug Project.

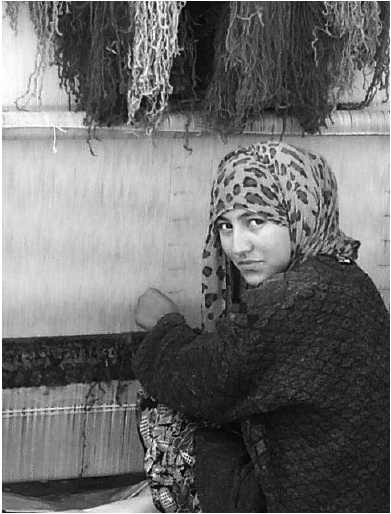

Many of Opie’s rugs are imported from rural, Taliban-controlled areas, where home-based employment is critical, particularly for women. Most women cannot leave their homes without being escorted by a male relative, meaning that they especially benefit from the project, which allows them to support themselves and their families in the safety of their homes, close to their children. And because weaving is so historically and culturally ingrained in Afghan society, the Taliban do not interfere with it.

Although the Taliban is no longer the dominant power in Afghanistan, its influence and lingering presence still haunts the country today.

“[In Afghanistan] insecurity and continuation of various forms of violence continue to be a threat to women,” says Shahla Ahmadi, president and founder of the Afghan-American Women’s Association, who spoke at Opie’s panel. Her organization helps newly arrived Afghan women adjust to American culture. Ahmadi, who was born in Afghanistan but left in the 1980s, sees Opie’s project as a way of connecting Afghan women with the rest of the world, ultimately bringing stability to the country.

“It’s important to have a relationship with those in the community surrounding the work,” she says. “Only with sustainable programs can we bring real and lasting change in the life of aid recipients.”

Abigail Adams Greenway, one half of the DC-based duo Table for Two that provided the musical entertainment for the panel, also believe that giving the people of Afghanistan a chance to to take charge of their own lives is vital.

“I feel that it is extremely important to create an atmosphere of hope for the women and children and men living in Afghanistan,” she says, which is ultimately what she and her partner Masood Omari strive to do with their traditional Afghan music. “They must know that we, or someone, cares, and that is the beauty of these grassroots projects.”

Each rug produced by weavers for Opie’s project is unique, containing an array of traditional patterns that amount to, in Opie’s words, “art you can walk on.” The wool is hand-spun, providing work for many female spinners. Using vegetable dyes also provides agricultural jobs and protects the environment. It takes several weeks to make even the smallest rugs, but Opie orders all sizes and then sells them to dealers so that they may furnish homes throughout North America and Europe.

“We have an opportunity—I think a responsibility—to target some of our purchases in ways that nourish our own aesthetic needs and, at the same time, support stability in vulnerable parts of the world,” he says. “These locales seem distant from us but everything on our planet is connected. No one and nothing is separate, and this is especially true regarding the impact on world affairs from events in highly unstable regions. If we do not seize opportunities to promote stability in Afghanistan, a nation which can be saved, we will pay in ways that bring us grief, and help no one.”