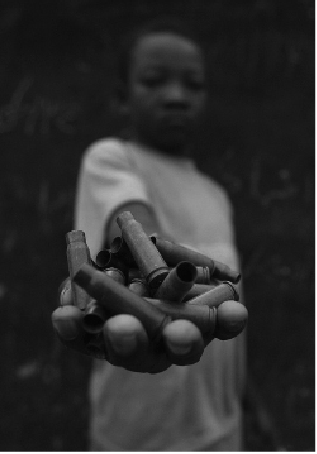

Accountability for Child Soldiers: Little Weapon

At ten years old, Dominic Ongwen was walking his typical route to school in Gula, northern Uganda. On his way, he was kidnapped by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). The LRA forced him to leave his family and become a part of an army responsible for recruiting hundreds of thousands of young kids like himself.

In the army, he became a major at the age of 18 and eventually second-in-command to Joseph Kony, the leader of the LRA. The LRA is associated with brutal massacres, summary executions, torture, rape, pillage and forced labor. Ongwen was a young boy introduced to these circumstances, but he eventually grew from being the victim to the perpetrator.

The LRA stripped Ongwen of his childhood—he was taken at an age when morality and the ability to make decisions fully develop. The children are often forced to perform ritual killings in order to prove their loyalty, meaning that they kill their own mothers and fathers. All ties from their prior lives are cut out, making the LRA all they have left.

“Victims need some sort of closure and some kind of recognition that what was done shocks the conscience of humanity,” said Nikki Souris, a professor at American University whose research examines the relations between moral development and criminal responsibility. “The victims and the victim’s families want Ongwen to be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.”

Ongwen was commander during some of the LRA’s most vicious attacks. According to a Human Rights Watch report, troops under Ongwen’s command killed at least 345 civilians and abducted another 250, including at least 80 children, during a four-day rampage in the Makombo area of northeastern Congo.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is currently trying Ongwen, now 41, for the crimes he committed since he turned 18—though some question whether Ongwen should receive leniency given the horrible circumstances he faced.

Author Erin Baines described Ongwen’s situation in her work on perpetrators of political crimes.

“Ongwen is like a dog sent to get meat,” she said. “They made him fight against his own people so that he is not able to return home and live with the people he hurt. He just worked on order and became a leader because of his discipline in following orders. We are like dogs because as the dog grows, it follows what it sees.”

While the LRA formed in Uganda before spreading to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and South Sudan, it is not the only army in Africa who enlists child soldiers. Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Libya, Mali, Chad, Uganda, Liberia, Congo, and Mozambique are only some of the countries across Africa that kidnap and recruit children with paramilitary organizations. Children are easier to manipulate than adults, making them prime targets for these armies.

For Thomas Squitieri, former foreign correspondent for USA Today, witnessing child soldiers firsthand in Liberia put that idea into perspective.

“The experience was shocking because I could not believe children so young would not be playing soldiers, but actually being soldiers,” Squitieri said. “I don’t think they realized the difference.”

Squitieri witnessed many horrifying acts as a war correspondent, but the child soldiers he encountered were deeply troubling to him. Fanaticism troubles him, he said, and these soldiers were fanatic about doing whatever their leader told them to do.

“These young boys were looking up to their leader as almost like a messiah, a cult leader,” Squitieri said.

Child soldiers are not exclusive to Africa either. Today, ISIS actively indoctrinates children, taking over local education systems and teaching young children that God wants them to join ISIS and fight for their cause.

“When they were in the LRA, they were something. They were commanders, they had freedom. They could loot and take what they want, when they want. They were their own masters.”

According to another Human Rights Report, ISIS offers free schooling in Syria, along with military training and weapons, essentially creating a generation of fighters for ISIS. Also, ISIS often exploits children with mental disablities, convincing them to volunteer for suicide missions.

The U.K., the U.S., China, India, the Netherlands, Canada, France, New Zealand, Germany and Australia allow minors in the national armed forces, although usually under very strict conditions, according to author and child soldier expert, Mark Drumbl.

Children were also enlisted in the army during America’s Civil War. These kids were 16 and 17 years old, many of whom volunteered to join.

“Many U.S. volunteer soldiers actually fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan are barely over the age of eighteen…They are not child soldiers and, hence, are not a protected class. But, still, when tragedy strikes they are often referred to as ‘just kids,'” Drumbl said.

A lot of children also volunteer to join the LRA and ISIS. Some like the power they get when joining these armies. Kasper Agger, a member of the non-profit organization Enough Project, which focuses on ending crimes against humanity in Sudan, Congo and Uganda, offered his perceptions of how ex-combatants felt before and after leaving the LRA.

“When they were in the LRA, they were something,” Agger said. “They were commanders, they had freedom. They could loot and take what they want, when they want. They were their own masters.”

For some children, these armies provide an escape from the poverty they usually face. Children have different experiences depending on where they grew up. At 15, people in Uganda are usually already married and working. At 15, they are considered to be adults who must care for their families and put food on the table.

In the U.S., 15-year-olds are still freshmen in high school. Because of these different experiences, it’s hard to create an international law that says what age children officially become adults. Once children become adults, they become criminally responsible for their actions.

To say people can make rational decisions on their 15th or 18th birthday draws a firm legal line between childhood to adulthood. Psychologically, this may not be reflected. According to a study conducted by the National Institute of Health, areas of the brain affecting decision-making do not fully mature until people are well into their 20s.

The ICC holds people responsible for crimes committed at the age of 18 and above. Other courts will hold child soldiers responsible for crimes committed before age 15. Because of this discrepancy, there is a push for a “Straight 18” position, which will make all courts hold child soldiers accountable for crime committed at 18 years or older.

This would apply everywhere, which helps create stability and fairness in the justice system. However, it could also ignore the different circumstances children face depending on where they live.

In Uganda, the courts gave child soldiers amnesty if they left the LRA, meaning they were not punished for any crimes.According to a Human Rights Watch report, the Ugandan government gave more than 12, 906 people affiliated with the LRA amnesty as of 2012.

“Everyone knows someone who was with the LRA at some point, most of them against their will,” Agger said. “Persecution is not the answer that people seem to be looking for, but maybe compensation and the government recognizing some of the atrocities they were behind…I think that matters more than punishment.”

The Ugandan government also did not follow through with a lot of the promises given to returning child soldiers to make their transition back to the community as easy as possible. While most children are happy to be free from the LRA, others express frustration.

“Some child soldiers even say if they had the chance, they would go back to the LRA,” Agger said. “When you are in a rebel group, you have an objective, a purpose.”

According to a report by Human Trafficking Center, the Ugandan government did enact a Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration policy for returning soldiers, but there wasn’t much organization in the program, so the government relied primarily on NGOs to run it. Most NGOs pulled out of Uganda after 2006, when the conflict seemed to die down. This only provided short-term relief, but in the long-term it left many ex-combatants feeling betrayed.

“They found themselves sitting in a small village in northern Uganda, surviving on one meal a day, not being able to go to school, no job,” Agger said. “They really don’t have a future.”

As for Ongwen, there is still a debate about whether he should be given leniency for his actions committed at 18 and above.

“I think we have instincts for excusing those who have been through really horrible circumstances,” Souris said. “But we also have instincts for saying you should know better since you were a victim of these circumstances.”