DC'S Native Sound: Where's GO-GO Going?

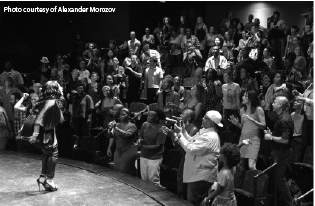

The spotlights shine on women in tight black outfits and high heels belting contemporary hits to an enthusiastic crowd. The all-female band backing them grooves to the beat. The audience loves every second of it—people are on their feet clapping, dancing and smiling from ear-to-ear.

This isn’t a show at the 9:30 Club, however, or any other mainstream concert venue in the DC area. It’s a performance by all-female go-go group Be’la Dona at the “Crank & Groove: A Go-Go Love Story” event held at the historic Atlas Theatre over the weekend of Sept. 13. Arranged by Speakeasy DC, the event was the place for go-go performers, experts and aficionados to share their go-go stories.

Nina Mercer, a playwright and professor at Medgar Evers College, shared her go-go story at Crank & Groove. Mercer grew up heavily involved in the go-go community. Her father semi-managed the popular band Experience Unlimited and was a legal representative for local musicians and record labels. Nina eventually became a dancer for the band as a teenager and provided choreography. Go-go allowed her to perform often, and by 16 she was able to choreograph dances for music videos and feature films. A summer job through a youth employment program dancing and bringing performance to parks in all four quadrants of DC gave her the opportunity to perform and craft her skills as a professional artist.

“My love for the music and the culture expanded beyond professional expression,” Mercer said. “My [fellow dancers] and I would go out and that would give us confidence.”

Go-go is a musical phenomenon. While anyone in the world with an internet connection can discover new music every day, go-go has remained a sort of well-kept secret within the DC-Maryland-Virginia area’s black community.

Go-go music can be compared stylistically to funk, with heavy emphasis on bass and drums. The genre is also notable for its West African-influenced call-and-response vocals. But the most distinct element of go-go is the pocket—a steady drumline that is consistent throughout the entire song. The pocket keeps the song in line; the other instruments, particularly the bass, follow the pocket.

The go-go pocket is constantly evolving, but it must stay consistent throughout a particular song. According to well-known go-go musician Christylez Bacon, who presented his go-go story at Crank & Groove, “If you’re not in the pocket, you might as well be invisible. If you’re not in the pocket, you aren’t in the go-go.” Patrick “Go-Go Grover” Washington, another presenter at “Crank & Groove,”described the pocket as “the space in between the drums we all live in.”

Go-go originated as a response to disco, and could even be considered a response to the hip-hop and rap culture that has dominated airwaves across the country and the world. Yet traditional go-go music hasn’t infiltrated mainstream radio airwaves, making it unique to DC. It is a cornerstone of the city’s culture despite changes in the music industry and its trends.

The singular example of go-go’s potential to infiltrate the mainstream hip-hop culture is Wale, a rapper and DMV native. Raised in Prince George’s County, Maryland, Wale (born Olubowale Victor Akintimehin) was involved in the go-go community before he transitioned into his career as a rapper. His music is influenced by go-go, and select songs have distinct go-go elements. Wale gained local fame in the mid-2000s with his song “Dig Dug,” a tribute to the late percussionist Ronald “Dig Dug” Dixon from the go-go band The Northeast Groovers. The song was hugely popular among locals, gaining airtime on radio stations and subsequently catching the attention of British producer Mark Ronson. Working with Ronson garnered him industry attention, and Wale was able to sign with Interscope records in the late 2000s to release his first album, Attention Deficit in 2009. The album included a straight go-go song called “Pretty Girls.” Natalie Hopkinson, a writer for The Washington Post and The Root who wrote her doctoral dissertation on the culture surrounding go-go, certainly considers Wale to be a member of the go-go culture.

“[Pretty Girls] was on the radio and topped the charts for a long time, and he really didn’t do a lot to it to change it to make it a hit for his album,” Hopkinson says. “It was a go-go song. And then he’s embraced the culture in a way that other hip-hop artists haven’t.”

Wale’s second major-label album, Ambition, was his first on hip-hop mogul Rick Ross’s label Maybach Music Group. Compared to his first studio album, Ambition all but abandons go-go influences, like the inclusion of a pocket. Out of 17 songs on the album, only three have an inkling of any go-go inspiration; these include the opening song “Don’t Hold Your Applause” and “Sabotage.” By distancing himself from his go-go roots, it is possible that Wale was simply making a mainstream rap album with his new label.

Yet his third album, The Gifted, released in June 2013, has recognizable go-go influence, particularly in the songs “Clappers” and “LoveHate Thing.” “Clappers,” for example, suggests a pocket, yet the beat does not carry through the song. Furthermore, at the end of the song, Wale repeats the phrase “Rest in peace to Chuck,” a shoutout to the late musician and go-go star Chuck Brown.

Brown’s death in May 2012 sparked a noticeable resurgence in the DMV’s interest in go-go music. Brown, affectionately known as the “Godfather of Go-Go,” truly transformed the genre from a stray offshoot of funk music into a genre and culture all its own.

Go-go music has evolved since Brown, fueling a debate over the music between “old heads” and “new heads.” So-called “old heads” believe traditional go-go styles and venues must be preserved and performed for posterity. Any of Chuck Brown’s songs, especially hits like “Bustin’ Loose” and “Block Party,” exemplify the sound “old heads” are trying to preserve.

The “new heads,” which include the youth fueling the present and future of go-go, have created quicker and more “hardcore” styles of go-go, including the subgenre “bounce beat.” Bounce beat has a faster tempo, with a heavier base and greater use of vulgar language. One of the more popular bounce beat bands, TCB, has “made over” current hip-hop songs, keeping the lyrics but transforming the accompaniment to include a pocket.

Although traditional go-go music is unique to DC, one group from Reston, Virginia has shown signs of infiltrating the mainstream. RDGLDGRN (pronounced Red Gold Green) has been touring nationwide and plans to make international appearances with a genre they call “indie go-go.”

The group’s style, according to its Facebook page, “takes hip-hop infused punk and indie rock to create something refreshingly unique.” While RDGLDGRN has had some success connecting with listeners outside the DMV area, the band said in an email that “the only people that recognize the go-go influence in our music are the people who have heard go-go at least once before. No one else knows what they’re hearing, they just know they like it.” After all, the music is not traditional or “pure” go-go—it contains rock and hip-hop elements that give it a greater chance of reaching an audience outside the DMV area.

Though go-go has always been considered an open community for expression in DC, its past is rocky. Indeed, as an “underground” genre that hasn’t penetrated music scenes outside the DMV, the violence and drug culture that surrounds non-commercial music was highly concentrated. Mass numbers of drug-fueled fights and casualties around the go-go scene led to heightened police presence that persists to this day.

In 2010, the Washington City Paper published a story detailing DC Metro Police Department’s biweekly “go-go report,” collected by its “hush-hush” intelligence branch. This report details where known go-go shows are going to occur, which bands are playing, and what time the shows are slated to start and finish. At the time of that story’s publication, hardly anyone—particularly go-go musicians and their management—knew that the “go-go report” existed. But they weren’t surprised. Quoted in the City Paper’s story, Ben Adda, go-go band TCB’s manager, said that he felt targeted by MPD. The go-go report’s continued existence, well after the violence surrounding go-gos has greatly diminished, is a strong indicator of MPD’s wariness of go-go and the individuals involved in the go-go community.

To this day, select music venues in DC refuse to allow go-gos, and some have been shut down by law enforcement injunctions. Hopkinson said she knows of at least one case in which the Petworth neighborhood commission denied a new music venue its liquor license unless it banned go-go.

Kids aren’t letting it go, and [go-go] continues to be the signature of DC, but we have to make it happen. It takes a whole community of people to say that we aren’t letting this go.

Go-go was always—and continues to be—an industry, with specialized designers, artists, promoters and musicians benefitting from packed shows every night of the week. For many African-Americans living in DC, especially during the “Chocolate City” era, go-go provided opportunities for expression and employment that didn’t exist elsewhere. In the 1980s, when mass incarceration was on the rise and there was a distinct lack of economic opportunity and mobility in the DMV, go-go enjoyed popularity as an apolitical musical escape mechanism. Perhaps go-go never achieved widespread popularity because it was born of problems too DC-centric to foster growth outside the community.

Many forces are poised against go-go culture: gentrification and the changing culture of the neighborhood schools where many musicians and artists met and grew up, and the backlash against violence associated with go-go.

There are, however, some bright spots in go-go’s future. Hopkinson noted that shows are still packed every night.

“Maybe they might hide for a while, and they might change the name—in some places they call it this and other places they call it that—but they’re very old, and go-go is one of those things, the whole thing is not a new invention,” she said.

Mercer said she’s positive about the future of go-go as a genre and as a community.

“Kids aren’t letting it go, and it continues to be the signature of DC, but we have to make it happen,” Mercer said. “It takes a whole community of people to say that we aren’t letting this go.”