Refugees Seek Asylum: Borderline Justice

April 26, 2016

All of the sudden everything around Ahmed Badr turned dark and cloudy. His previous life—his possessions and the house in which he’d created his dearest memories—vanished the instant the bomb dropped. His family told him that it was time to leave, transforming Badr’s eight-year-old life into a statistic: he was suddenly one of the world’s 19.5 million refugees.

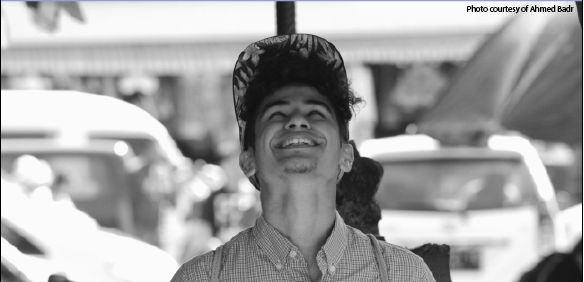

Today, Badr is a 17-year-old refugee from Baghdad, Iraq living in Houston, Texas. According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), he is one of the 11,778 refugees from Iraq resettled in the United States.

“As a kid, you don’t really understand what tragedy means,” Badr said. “We went home and then I saw for myself.”

After months of trying to make a new life in the economically unstable country of Syria, the family found hope in the form of a bus driver. The driver told Badr’s father that he could apply for resettlement in either the United States or the United Kingdom.

“The thing about this program was that only one percent of the people that apply get accepted,” Badr said. “But my dad thought we didn’t have anything to lose, so we went for it.”

Badr was lucky his family’s case was actually addressed. However, he still went through months of security measures.

“We had six months of interviews in different places in Syria,” Badr said. In the midst of the expansive refugee crisis, the time span for resettlement in the United States has only gotten longer.

The U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants requires 13 steps before a refugee is allowed asylum in the United States. According to Defense One, an online news site, it takes at least 18 to 24 months to resettle a Syrian refugee, resulting in the resettlement of fewer than 1,900 of the 20,000 applications filed since 2011. Following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the U.S. tightened security measures for resettlement, lengthening the time that people must wait for their case to be considered.

“When you look at this crisis, the area where you have a security problem is human security,” said Kate Tennis, a speaker for the American University Migration Crisis panel and a graduate student at AU. “Thousands of people are dying on terrestrial routes and maritime routes. That’s the security problem.”

According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, there were still 82,175 pending asylum cases as of March 2015. The U.S. pledges to take in only 15,000 more refugees in fiscal year 2016, in addition to the current maximum of 70,000.

“[There are] politics of fear that we have seen going on in the United States since 9/11 and an overabundance of caution due to the anxiety around the Islamic State,” Mary O’Toole, a reporter for Defense One Politics, said at the panel.

Following the start of the Syrian conflict in 2011, there have been 4,289,792 registered Syrian refugees at the time of print, according to the UN Refugee Agency. In comparison to the 85,000 total refugees that the U.S. has pledged to accomodate in 2016, Germany pledged to take in 800,000 refugees this year alone. They have also implemented more efficient ways to speed up their asylum process. According to Asylum in Europe, it takes Syrian refugees 4.2 months to receive asylum even in Germany, a country that has taken on a significant amount of the European refugee influx.

“It’s important to show support for our own human brother, no matter what color, what race, what religion. We bond together.”

Emma Ashford, 32, a Visiting Fellow in Foreign Policy Studies at the Cato Institute, is from the United Kingdom. At the migration panel, she compared her experience applying for U.S. citizenship to the difficulty of applying for asylum: “The requirements for getting asylum status in the U.S.—[as] someone who just went through the citizenship process as a West European, white, English-speaking immigrant—was a nightmare,” Ashford said. “So, it’s a very high bar for these people, which is why the processing is so slow.”

Many refugees from Syria are fleeing to Germany to escape the effects of the civil war that has been going on since 2011. Fadi Mcleash, 23, from Damascus, Syria, was oblivious to the severity of the war when it first began. However, two years into the civil war, he knew that he needed to leave Syria.

“In 2013, it started to rain mortar shells in Jaramana,” Mcleash said. “We had like 14 mortar shells a day and that was considered normal. So that was a really tense time to live in.”

Mcleash is one of the 216,973 Syrian refugees currently residing in Germany. After meeting AU professor Alex Cromwell, Mcleash agreed to Cromwell’s idea of establishing a GoFundMe page in order to raise money to flee Syria. The GoFundMe Page was a tremendous success. Through the help of donations, he raised a total of $2,681 to finance his journey. Mcleash and a small group of friends, who were also leaving Syria and traveling to Germany, embarked on the dangerous journey crossing the Mediterranean. With one piece of mortar shell in his leg and another in his hand, he knew that the only way to remove the shrapnel required fleeing his home country.

“All of the good doctors in Syria are [sic] either traveled outside of Syria or have passed away because of mortar shells,” Mcleash said. Despite these harsh circumstances, the U.S. has been slow to respond to pressures for changes in their policies.

“Many politicians are using fear to prevent policies that they don’t like,” Ashford said. “And with the line between humanitarian needs and security needs, we should certainly be relaxing the security needs right now to deal with the major humanitarian crisis.”

Because of the strict procedures to gain asylum in the United States, countries such as Jordan, which are not economically capable of handling the large influx of refugees, are the ones who are forced to handle it.

“Jordan is a great example where one in five of the population [are refugees],” O’Toole said. “So if their resources are so stretched, and the U.S. has unique resources to deal with the problem, I expect more of a response [from the U.S], being such a global leader.”

While Badr was able to find refuge in the U.S., the U.S. is not making it an easy process for current refugees to get asylum. Out of the 12 million Syrians that have been forced to flee their homes since the start of the conflict, the U.S. has only taken in 1,500. Refugees need resources that the U.S. has and that other Middle Eastern countries currently taking in millions of refugees are struggling to provide.

“I remind myself every day to remember why I left, even when I get homesick,” Mcleash said. “In Syria, we don’t even have freedom of speech. And as you can see, I can talk for hours, so I need that freedom.”

Countries that provide asylum to refugees are allowing them to escape the presence of war and an oppressive government. They provide a place of solitude that rids refugees of constantly fearing a mortar shell or car bomb.

“It’s important to show support for our own human brother, no matter what color, what race, what religion,” Mcleash said. “We bond together.”