Revolutionary Tourism: Cuba's Deal with the Devil

Mural, Havana. “In every neighborhood, Revolution.” The Cuban Revolution of 1959 brought cataclysmic change to the island. For the first time in centuries, Cuba was free from foreign domination. Over the course of decades, the Revolution blunted economic stratification, reduced racial segregation, eradicated illiteracy, and brought Western health standards to the Third World nation. It was all made possible through Cuba’s extensive economic ties to the Soviet Union.

Resort, Cayo Santa Maria. But when the Soviet Union collapsed, Cuba’s economy was sent reeling, sparking the worst economic crisis in the nation’s history. Then-president Fidel Castro proclaimed that the Revolution had to make a “deal with the Devil” to survive. The Revolution turned to foreign tourism in hopes of finding an economic jolt.

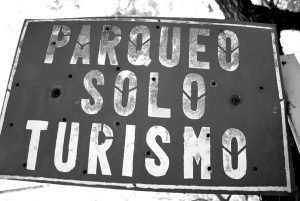

Town square, Santiago. The need to please deep-pocketed foreigners proved to be a paradox for the ideals of the Cuban Revolution. This sign reads “tourism parking only.” This unembellished inequality emerged only after 1990 and is still jarring to a Cuban populace accustomed to an ethos of equality.

Fishermen, Cayo Santa Maria. Cubans gather starfish to sell to tourist hotels as decorations, part of a mass labor migration into the tourist industry. Cubans speak of teachers who became taxi drivers and doctors who became bellhops, all in pursuit of much-needed tips from tourists in foreign currency.

Souvenirs, Trinidad. 1950s-era American cars: no longer just a utilitarian mode of transportation, Cuba’s automotive icons are now a source of quick cash.

Beach, Cayo Santa Maria. One of the Revolution’s first acts was to make all Cuban beaches public. And while Cubans still enjoy the benefits of their beautiful Caribbean coast, it’s vacationing Spaniards and Canadians who frequent the most pristine beaches.