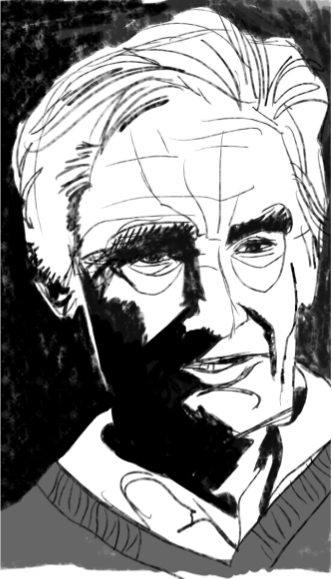

My Encounter with Howard Zinn

I’m one of those hardheaded young people with the stubborn belief that the world has the potential to be a much better place than it is now. Back in high school, I stumbled across “A People’s History” at the library. I tore wide-eyed through 600 pages of Zinn’s alternative history, in which the heroes were not powerful white men, but everyday folks, who resisted their marginalization in American society — women, American Indians, civil rights activists, war resisters. The book was inspiring and engrossing, and it became a key part in the development of my obstinate idealism.

So imagine my excitement this past summer when, away on a family vacation in the backwaters of Cape Cod, I learned that Zinn was living just a half-mile up the road from our rental cottage.

I decided to write him a letter. The gist of it: “Hey, Mr. Zinn: I’m a college student who’s read your work, and I think you and I have some common interests. I’d be delighted to meet you for coffee or something. I’m here until Friday.” I dropped the letter at the post office and expected never to think about it again.

A few days later, my cell phone rang: “Hello, Chris? This is Howard Zinn.”

Zinn and I met at a local coffee shop, where he rebuffed my efforts to pay for my own muffin and iced tea. We sat down at a table, legendary writer and activist across from idealistic college pipsqueak. We talked about politics, my family, my research in school, the passing of his wife in 2008. I remember asking him how he was able to spend his life crusading for progressive beliefs, often to no avail, but he never seemed to get worn down. I explained that I grew fatigued at times, trying to stand up for such unpopular causes in college classrooms and at family dinner tables, only to be drowned out by a chorus of objection and disagreement.

With a smile on his face, he said, “You just have to relish those battles.” He added that while many progressives may feel they’re alienated, you’re never as alone as you may think.

“There are lots of young people doing good work out there,” he said. “It may seem like you’re alone, but there are millions of people in this country with progressive beliefs.”

After an hour or so, we walked out to his car. He gave me his email address, and then took off in his clunky green sedan with a “War is Not the Answer” bumper sticker.

Zinn built his intellectual reputation (“A People’s History” has sold nearly two million copies) on the importance of everyday folks. I was always impressed that he had time in his day for one, too, and that he took an interest in an ordinary college student — a stranger — who was trying to fight the same “battles.” We’ll have to fight even harder now that he’s gone.