American’s new aesthetic: National Geographic Society’s gift to campus

Construction underway for artist Elyn Zimmerman’s newly renamed sculpture.

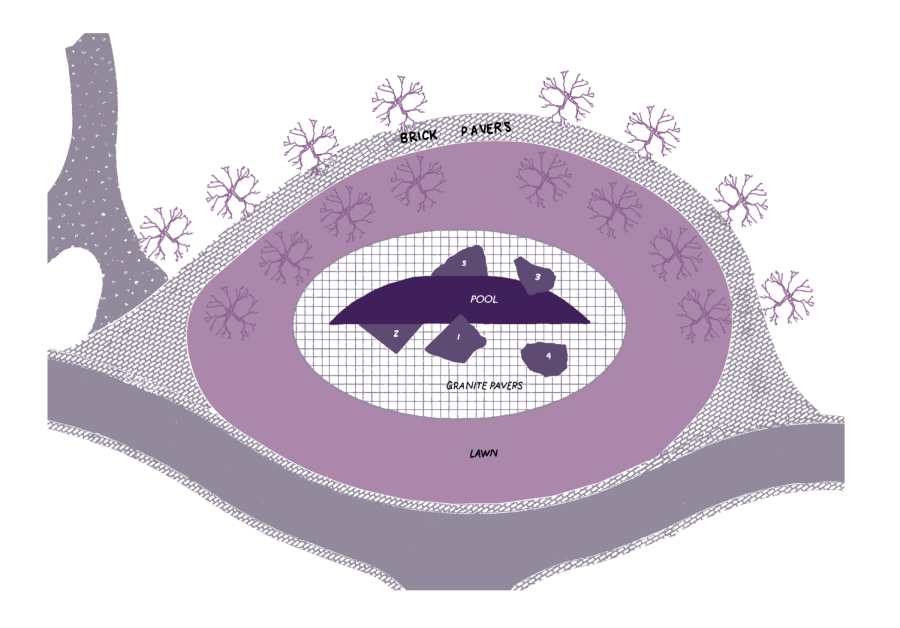

American University community members will soon see a large rock sculpture along their daily campus walk. Sudama, formerly known as Marabar, will sit in front of the Kogod School of Business, across from Katzen Arts Center. Sudama has been reformed into a crescent shape to fit the new location, and according to a Sept. 14 university memo, is expected to be unveiled around the end of December.

“Marabar will be a unique feature on our campus and contribute to our scholarship in the arts,” the memo said.

“I think that what students will get out of having the sculpture on campus is … an appreciation for … artwork,” said American Artist Elyn Zimmerman, who began working on the sculpture in 1981.

Zimmerman taught university art classes in New York and California between 1974 and 1986 and has been a visiting professor of architecture at several different colleges, including the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Construction has been underway at American University since mid-September for the relocation of Sudama, which stood in front of the National Geographic Headquarters in the district from 1984 to 2021.

“It’s recognized as a masterpiece in the genre,” said Dr. Jack Rasmussen, director and curator of the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center.

The relocation process was fully paid for by National Geographic, according to Steve Callcott, who is the deputy preservation officer at the Office of Planning.

The process began when the district Historic Preservation Review Board (HPRB) unanimously voted in Aug. 2019 to approve a renovation plan for the National Geographics campus, which did not include Marabar according to the New York Times. The future of the sculpture was undetermined.

“The primary responsibility [of HPRB] is to designate properties as either landmarks or historic districts properties that have been determined to meet criteria that represents important aspects of the city’s history or architecture,” Callcot said.

For a property or piece of art to be designated by the Historic Preservation Review Board, an estimated 50 years must have passed since the building or piece’s construction.

“The issue was more about the fact that Marabar was not a historic resource. It may be a valuable artistic resource, but it was not one that fell within the context of the Historic Preservation Review Board’s role in evaluating alterations to historic properties,” Callcott said.

Initially, Zimmerman said she did not want to fight City Hall alone.

In January 2020, associates of The Cultural Landscape Foundation, a nonprofit in the district that works to preserve architecture, sculptures and landscapes, reached out to Zimmerman to preserve the sculpture.

A campaign of artists, museum curators and others soon gathered to fight for Marabar’s survival.

“It was really a result of letters that were generated from The Cultural Landscape Foundation,” Callcott said.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation said in a March 2021 letter that National Geographic’s proposal “had not adequately illustrated the installation nor appraised the HPRB of the artwork’s importance.” As the movement to save Marabar expanded, more letters were posted on the Cultural Landscape Foundation website. “To erase a major work of art such as this, would be a crime, in my opinion,” said New York artist Martin Kline in a letter written in 2020.

Within months, the Historic Preservation Review Board soon received dozens of similar letters fighting for the Marabar’s survival and eventually revisited the issue. AU was later chosen as the new site and installation began on Sept. 19.

The original inspiration for Marabar came from the E.M. Forster novel, “A Passage to India”, which talks about rock-cut temples carved out of solid rock. These caves exist all over India with naturally rough outsides and polished insides.

“When the National Geographic and their architects at the time came to talk to me about doing something with rock and water, I immediately thought of this, the description of the caves,” Zimmerman said.

“I think that it’s really important for people to see the history of different perspectives that we don’t see here in D.C., so if something is being donated to our campus and people can learn about that then that’s really helpful,” said AU sophomore Abbey Boyce.

The relocation of Marabar to American University was scheduled to be completed in the summer of 2022 but was delayed due to the discovery of a communications cable running underneath Massachusetts Avenue. The construction could not begin until mid-September due to the cable.

With Marabar’s unveiling just weeks away, there are already plans for an exhibition of Zimmerman’s work next summer at the Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, as well as to commission a piece of work from the music department to be played on the site this spring.

“So we’re gonna use it a lot, I think, and everybody over here is very excited about it,” Rasmussen said.

This article is from AWOL’s 31st print edition.

Daniel Rosato is a freshman studying journalism with a minor in Spanish.

Daniel Rosato (he/him) is a freshman studying journalism with a minor in Spanish. He is from Long Island, New York. Outside of journalism and writing,...

Casey Bacot (she/her) is a senior studying journalism. She enjoys tea, hanging out with her cat, and video games.