Private politics

Intimate partner violence as a human rights violation

A new ruling by Attorney General Jeff Sessions may jeopardize domestic violence survivors’ ability to seek asylum within the United States. On Monday, June 11th, Sessions overturned asylum protections for survivors of domestic abuse and gang violence.

Sessions wrote, “An alien may suffer threats and violence in a foreign country for any number of reasons related to her social, economic, family or other personal circumstances. Yet the statute does not provide redress for all misfortune.”

Additionally, the new ruling states that a survivor of domestic abuse or gang violence must demonstrate that their home government “condoned the private actions or demonstrated an inability to protect the victims.”

The burden of proof, which all too often falls on survivors of gender-based violence, could prevent thousands of individuals from receiving asylum protections they desperately need. Of approximately 711,000 pending cases for asylum, 230,000 cases are from Central America and Mexico, areas plagued by domestic and gang violence.

Placing the burden of proof on survivors also places them in greater danger.

“Survivors are most at risk for fatal violence when they turn to the police for help,” Cori Alonso-Yoder, practitioner-in-residence of the Immigration Justice Clinic at the Washington College of Law said. “Adding this requirement will only place them at greater risk.”

Seeking asylum:

To seek asylum in America, an individual must be persecuted or fear of persecution based on their race, religion, nationality, political views, or membership in a particular social group. Based on this definition, people looking to escape intimate partner violence and abuse constitute a “particular social group”.

Alonso-Yoder explained that the definition of asylum seekers expanded to include domestic violence survivors in 2014.

“[The decision] set a precedent many years coming based on the concept that in certain societies, women are often a social group facing persecution,” Alonso-Yoder said.

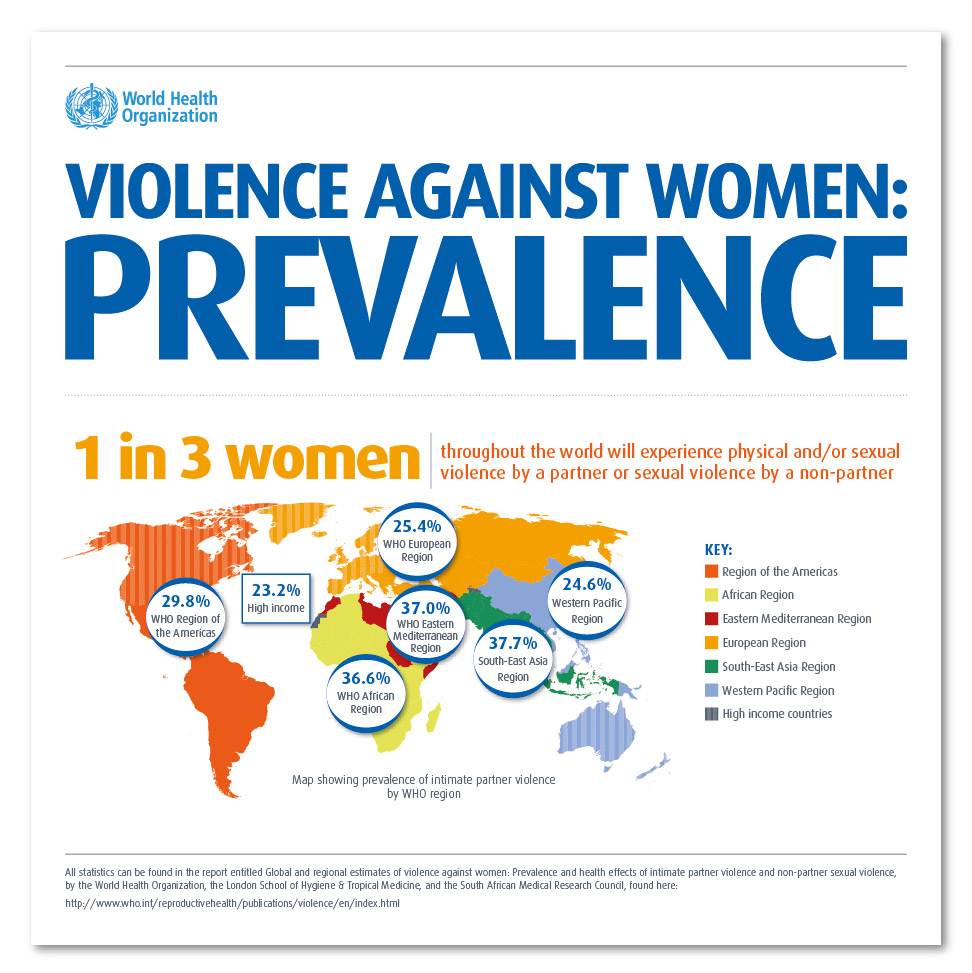

According to the World Health Organization, globally more than one in three women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence with an intimate partner. Many flee to other countries to escape from dangerous situations.

Sessions’ decision, immigration attorneys have said that thousands of pending claims may be overturned from women, children, and men who are fleeing their country.

“There has been broad documentation about the targeted violence women in particular face in the home and in their communities from either an intimate partner or criminal gangs,” Tarah Demant, director of the Gender, Sexuality, and Identity Program at Amnesty International USA, said.“Those fleeing their country to save their lives should be met with compassion and a rights-based framework, not one that fundamentally denies that women’s rights are human rights or that domestic violence isn’t really “serious” violence.”

Violence against women, especially intimate partner violence, is a serious public health issue. Although Sessions plans to reduce administrative burdens by limiting the number of applicants reviewed by immigration services, his decision could be detrimental to people worldwide who are desperately looking for opportunities to escape abusive relationships and situations.

By denying access to survivors of “private violence”, the United States reinforces the notion that the health and safety of people, especially women, worldwide does not ultimately matter. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 3 states, “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.” Sessions’ decision denies domestic violence survivors the right to security and potentially the right to life as they are turned away from asylum.

“Barriers to health and safety are violations of human rights,” Dr. Suyanna Barker, Senior Director of health equity and community action at La Clinica del Pueblo said. “There is no right to life without health and guaranteed safety.”

This new rule invalidates domestic violence survivors’ experiences, as though the persecution and abuse they have experienced is not “enough” to gain asylum in the United States.

“The rule has broad implications not just for domestic violence survivors, but for other groups seeking asylum such as members of the LGBT community,” Alonso-Yoder said. “It undercuts asylum ultimately for people who are not directly persecuted by their home government.”

Through domestic abuse, whether it be physical, emotional, sexual, or economic abuse, human beings’ lives are devalued and diminished under this new law.

As a nation, government officials should not treat each domestic violence case as a singular event but rather a pattern of similar cases where survivors are devalued and treated poorly.

Treating domestic violence cases as singular events discounts the intersection between gender inequality and domestic violence internationally. A report by the World Health Organization highlights how social norms of gender inequality increases the risk of violence against women and hinders the ability of survivors to seek protection.

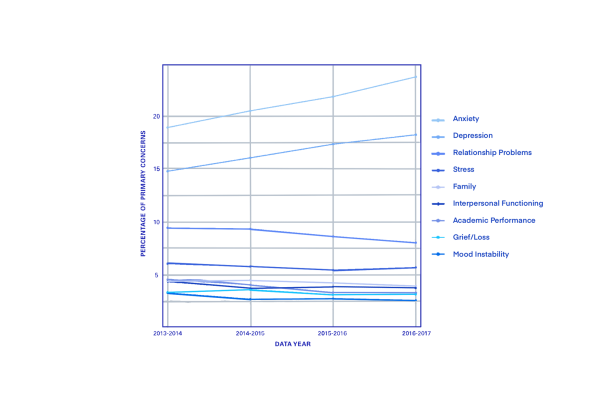

Treating these cases as a pattern can help identify ways to prevent abuse and empower women in unsafe situations. Additionally, treating domestic violence cases as singular events disregards the public health issues that arise from violence, including physical harm and mental health issues.

“Violence against women is a human rights crisis—and it doesn’t matter if it’s committed in the home or by the State: every woman has the right to live free from violence,” Demant said. “The notion that ‘private’ violence is somehow less “serious” or less deadly is not only wrong-headed, it is anti-woman and anti-rights.”

Physical and sexual violence engaged by an intimate partner can reduce the survivor’s bodily integrity and lead to a number of health conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder.

In fact, according to the National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma, and Mental Health, 80 percent of women who have experienced physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner report significant short and long-term mental health consequences, including PTSD.

Immigration attorneys like Boston lawyer, Matt Cameron, worry for their clients with histories of violent and abusive pasts. It is unknown currently how to address the situation.

Cameron told Reuters about of one of his clients, a domestic violence survivor, “This person had been through a lot of preparation…Now you have to tell them they don’t even have a case anymore.”

Survivors will experience difficulty being recognized for the violence they have faced under the new law, and may instead attempt to seek asylum for recognized reasons, such as religion or asylum. Alonso-Yoder explained that some immigrant attorneys have argued about a feminist political opinion as a reason to seek asylum for women who have stood up to their abusers.

“Many claims are pending and backlogged for years,” Alonso-Yoder said. “Now, when their cases are heard, survivors will not have the protection of the law as they previously did. It’s very unjust and unfair.”

The United States should maintain domestic and gang violence as vulnerable social groups that deserve protection and asylum to protect their health and safety. With Jeff Sessions’ decision, people that desperately need help must return to their countries and often abusive and dangerous living situations.

“This is part of a long line of attacks by the Trump administration on human rights, attacks which have been particularly virulent against women’s rights,” Demant said. “ Instead of thinking of ways to limit access to the basic right to seek asylum and making women’s lives more dangerous, the administration should be making policies that protect human rights.”

I'm a Senior majoring in Public Health. My areas of interest include health equity, housing access, and criminal justice reform. I have always been a writer...

I'm a junior majoring in Film and Media Arts! My areas of interest are women’s right, gun control, sex education, immigration, and healthcare! I love...