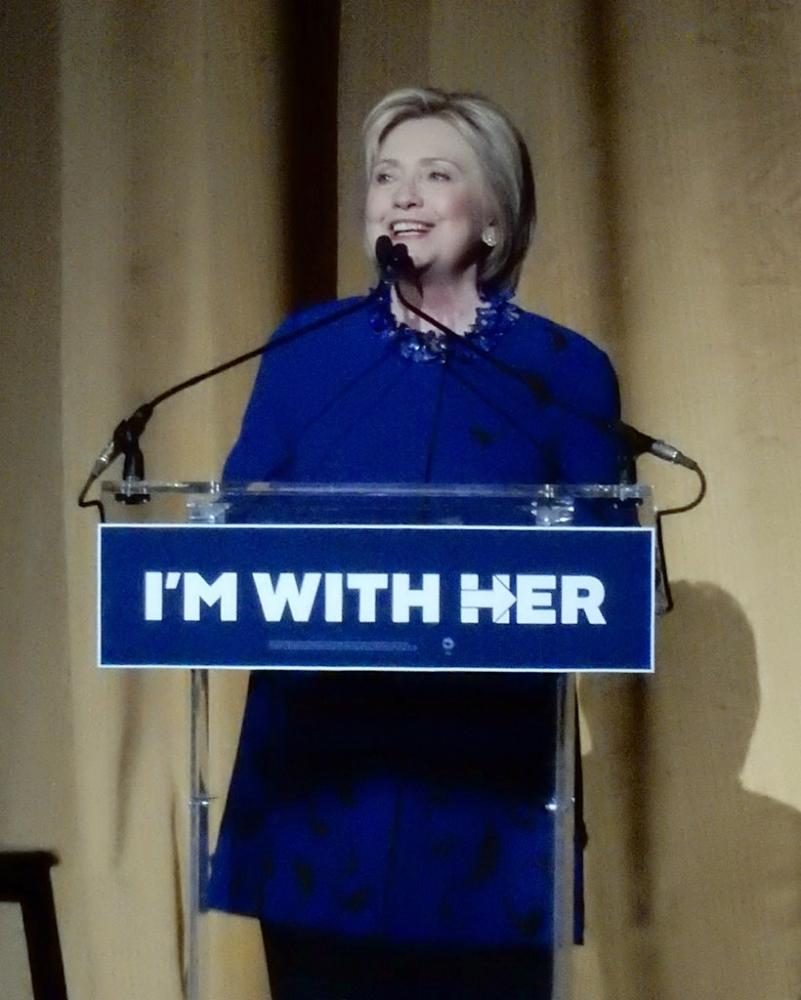

Opinion ||: I’m With Her: Progressive and Passionate About Clinton

I’m with her.

Not because she’s a woman. Not because she is the frontrunner of the race. Not because of her name brand recognition.

I’m with Hillary Clinton because she makes me passionate about politics, she is whip-smart on policy and the issues, and she is the most presidential. What does it mean to be presidential, and why does Clinton surpass Bernie Sanders in this regard?

To be presidential means to pass policy — both domestic and foreign — that benefits the American people and is either neutral or beneficial to the wider world.

The Cost of Fighting “The Establishment”

Clinton critics view her as part of the military-industrial complex that is widely established in American politics. Sanders supporters raise the question: Do presidential candidates need to exist within the “establishment?” Sanders says no, yet both he and Clinton are part of the “establishment” that Sanders rails against: while Clinton was a senator for eight years and Secretary of State for four, Sanders was a senator for eight and a representative for 16. They have both introduced hundreds of bills as senators and only seen a handful signed into law. They have both changed their mind on issues they voted on while in office (for example, Clinton on supporting the Iraq War, and Sanders on supporting Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill—interestingly, Hillary Clinton is more often associated with her husband’s bill as the powerless former First Lady than Sanders as a former voting member of the House of Representatives).

They are both, irrefutably, established politicians. The major difference in this election is that Bernie fights against the “establishment” by not taking campaign money from major corporations. Clinton, meanwhile, has accepted money from lawyers and corporations, including over $7 million each from Soros Fund Management and Euclidean Capital. Taking money from big businesses was seen for a while as a necessary evil democratic candidates had to engage in, but Sanders’ ability to withstand corporate backing shows that this evil is not so necessary. The idea that big money cannot buy a candidate is very seductive, especially to young voters like myself who see the financial system so stacked against their favor (see the slogan, “Billionaires can’t buy Bernie).

But here’s the thing about being “anti-establishment.” Sanders supporters laud him for not playing by the system’s rules or compromising on his values. And while admirable, this goes against our political system’s foundation of compromise. Sanders has always stayed true to the liberal cause, but he’s also passed far less progressive legislation than Clinton.

Passing Progressive Policy

While Sanders’ consistency is admirable, his inability to compromise, while idealist, has not always been a good way to create policy, which presidents need to be able to do. Clinton has shown she is able to compromise, to scale back on progressive values in order to achieve lasting progress.

In his eight years as a senator, Sanders co-sponsored five Republican-sponsored pieces of legislature; in the same amount of time, Clinton co-sponsored 27. Aside from the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, which mobilized important counterterrorism offices as we know them today, most of the Republican-sponsored legislation she co-sponsored, which was not benign (handing out congressional gold medals and renaming post offices), was progressive: funding research on cancer, pediatric drugs, traumatic brain injuries, autism and preemie births; strengthening AmeriCorps and federal finance transparency to the public; and funding human rights campaigns for Afghan women and the people of Zimbabwe. Clinton has a proven history of reaching across the aisle to promote policy that falls in line with liberal and progressive values.

Meanwhile, Sanders sponsored or cosponsored 31 democratic or independent pieces of legislation that became law, while Clinton sponsored or cosponsored 50 in the same amount of time in the Senate.

I understand why people are so passionate about Sanders and his message. I am too. Before Sanders emerged as a candidate, I was for Clinton; but then Sanders gave me serious pause. He has proved ample competition to Clinton in a manner that improves the product — progressive policy promises — that we are all getting. And while I want our country to pick up this progressive policy, I also see Clinton as the more successful president to do it. I see her as a fearless leader who will use her expertise and liberal stance to forge a similar path as President Obama — a president who, like Sanders, championed change on the campaign trail but found that, once in office, compromise is a more consistent and reliable currency.

Still, Sanders’ consistency is reliable and reassuring, and a very large part of me wants him to become president. However, when I actually think of a Sanders presidency, I am not confident in his ability to push through meaningful liberal and progressive legislation. Critics have already pointed out his poor record on turning progressive and socialist ideas into policy. Further, I see him facing many of the same roadblocks that President Obama did between 2010 and 2016, and I see him floundering on foreign policy with isolationist positions that not only delegitimizes the U.S. as a world leader, but allows other countries to take advantage of the void we leave behind in world affairs. I see him failing to be the president we want him to be. No matter how much I admire Sanders and want him to be a successful president, I think he represents a pipe dream. That makes me sad. It even makes me angry. Shouldn’t I take a chance for the most liberal candidate out there?

The answer is no — because he is not the best candidate. Clinton is.

I am not uncertain of Clinton. She has the experience, the contacts, the intelligence, the charisma and the progressive values I believe in (As a young female progressive, I agree with Clinton and Sanders on over 95 percent of their policies, according to the popular I Side With online surveys).

I think the major issue voters have with Clinton is not with her ability to pass legislation, but with their uncertainty over whether her legislation will adhere to the liberal policies she has promised of late, or more moderate positions from her past.

In short, I don’t doubt Sanders’ word, but I’m unsure if he’ll be capable; I don’t believe anyone doubts whether Clinton is capable, but people do doubt her word.

“Flip-flopping”

Sanders himself has criticized Clinton on “flip-flopping.” Many voters can, and do, see Clinton’s newer positions on LGBTQ rights, free trade, gun ownership, immigration and the Iraq War as examples of her pandering to the leftist democratic base rather than as genuine policy changes. Sanders supporters argue that Sanders has always been liberal on these issues. And while that may be true, calling Clinton’s changing positions “flip-flopping” is a political move that makes her look unreliable rather than honestly representative of a changing base. At the end of the day, our politicians are representatives of the American people. And while it is sad that the democratic base did not emulate Sanders’ liberality in the 1990’s, at the time, Clinton represented the people. She held more moderate positions on issues than Sanders, following the lead of other democrats such as Bill Clinton because the democratic base coming out of the Reagan and Bush administrations called for that level of moderation. And those in the know maintain that even in the 1990s, Hillary Clinton was a liberal champion to the left of many of her husband’s moderate White House staffers.

While she has changed her mind on issues since the 1990s and early 2000s, I do not see these changes as simply a front to garner votes, but as an honest response to the shifting democratic base. Clinton wants to respond to these shifts as a representative of the people. For those who argue that she did not do this while Secretary of State, they have to understand that the Obama administration’s high approval ratings shielded the party from understanding its own growing divide that we see in the primaries today. Now, thanks in large part to Sanders, she understands how the base has shifted, and how she, as a representative of the people, must likewise shift. The cynics may call this pandering. I call it being a responsible leader. She is admitting mistakes. She is evolving in her beliefs. She is acting like a president — listening to the needs of the people.

In his time in the Senate, Sanders was found to be the most liberal senator. While this is impressive, especially to an idealist young base of voters, Clinton’s track record is not only impressively liberal, but long. Clinton was the 11th most liberal senator in her time in office. And she has a longer record, passing twice as much legislation as Sanders in her eight years in the senate.

Clinton herself claimed in the first democratic debate, “I’m a progressive. But I’m a progressive that likes to get things done.” She is the pragmatic answer to Sanders’ idealistic but unreliable “political revolution.”

Foreign Policy

Both Clinton and Sanders currently hold similar progressive stances on many domestic issues, including raising the minimum wage, implementing campaign finance, supporting immigrants and the DREAM act, aborting private prisons and supporting women’s rights and survivors of sexual assault. When it comes to foreign policy though, the two veer apart. Sanders is isolationist, while Clinton believes in an active approach to foreign issues. Another big difference between the two on foreign policy is that Clinton has far more experience in foreign policy than Sanders as former Secretary of State, as well as far greater respect for the importance of a presidential candidate’s foreign policy.

Sanders’ disinterest in foreign politics is disheartening and the first sign he is not prepared to take the Oval Office. His apathy is reflective of the isolationist stance of many of his supporters who think that since Democrats got it wrong on Iraq and Syria, we should give up involving ourselves in foreign affairs at all. But this indifference is not realistic. While we do need to turn a spotlight on our domestic issues –– which are crucial in this election –– there are too many factors at play, particularly the rise of Islamic State, climate change and cyber security, to turn away from world affairs.

Sanders supporters say Clinton’s foreign policy experience does not equal success, often citing Libya. But careful analysis of Clinton’s activist position on intervention in Libya and Syria shows her desire to do more to prevent regional instability, often blocked by a weary President Obama; critics now agree that given our position on Libya and Syria, we did not do enough at the right time. Intervening can often be criticized and argued against, but Clinton understands that if and when we intervene, we need to follow through. Sanders anti-interventionist policy has its merits, but may not hold up to the foreign pressures that America currently faces, and that Clinton herself has already faced.

So What

I think Clinton’s ability to compromise and reach across the aisle, her track record with policy passed and her status as one of the most liberal members of senate during her time there makes her an excellent — and superior — presidential candidate.

If Sanders wins the election, I’ll be happy. I’ll be hopeful. But I’ll be worried about his ability to follow through on his promises and policies.

If Clinton wins the election, I’ll be happy. I’ll be hopeful. But I’ll be worried that maybe she will not follow through on all her recent promises and policies. I trust she’ll address all the major progressive domestic issues riling up the base, but don’t know if she’ll revolutionize the political system that got her elected. I’ll worry that maybe we should have given Sanders a chance. But I won’t worry about whether Clinton will lead us astray. I won’t worry she’ll fail to be presidential. At the end of the day, I want to be with both of them, but I’m with her.