Gentrification: The New Manifest Destiny

A walk around Southeast DC’s Capitol Riverfront on any given day features a picturesque view of the progressive America that Martin Luther King Jr. only ever dreamed.

Down K Street, a group of neighborhood kids — black, white and Asian — race between the 3rd Place apartment houses to play hide-and-go-seek. On Tingey Street, young black professionals gossip about job opportunities under happy hour umbrellas. Just off Water Street, mixed-race families picnic on the Yards Park green while same-sex couples debate real-estate prices on the nearby boardwalk.

On first glance one might conclude that the Capitol Riverfront is a pristine melting pot of black, white, Asian and Hispanic — a successful example of DC efforts to redevelop the area into a mixed-income community.

“Some call it gentrification. I call it finally waking up,” said Rodger Gairy, the black manager of Agua 301, as he motioned to a party of more than 50 Chinese people dining in the restaurant’s outdoor seating area. Such business, he said, would have never been possible when the streets were lined with stripper bars and dead warehouse clubs.

But undressed, the evolution of this utopia reveals a pattern of heathenish American history: exploit, dilute, repeat.

Far from DC’s urban landscape, tribal leaders often refer to the indigenous experience as being an invisible minority in the eyes of the government — that is until the government finds something it can take.

Competition over land and resources is an inherent tale as old as humanity itself. When the United States decided it needed to expand west to accommodate the growing population of its 13 colonies, the term “Manifest Destiny” was coined in 19th century newspapers that advertised “Indian Land For Sale.”

Individual treaties and broad legislation, such as the Indian Removal Act, sealed the indentured fate of the country’s indigenous inhabitants. Entire societies were forcibly removed from their flourishing homelands. Their cultures were interrupted and identities stripped as they were coerced to assimilate into a world beyond their means.

The Apache are the latest targets of exploitation, after Senator John McCain sold 807 acres of the tribe’s ceremonial and burial land to a foreign-owned copper mining company. McCain attached the government protected conservation land, known as Oak Flat, to the must-pass December 2014 defense bill and inflated his campaign contributions in the process.

Today, this thinking continues as historic black communities are uprooted and displaced in the name of city beautification.

While the Housing Act of 1954 intended to revive “unsafe and unhealthful” neighborhoods, in DC it focused mainly on disbanding the black community in the Southwest. Thriving families were forced to relinquish their homes and businesses and relocate to low-income housing at the Navy Yard.

Nearly 50 years later, their history was relived.

The Arthur Capper and Carrollsburg housing units were demolished as a part of DC Housing Authority’s Hope VI program, which transformed the Navy Yard to the flourishing and colorful Capitol Riverfront that stands today. In the ruins lay another community torn apart, another culture destroyed, to make way for the new world.

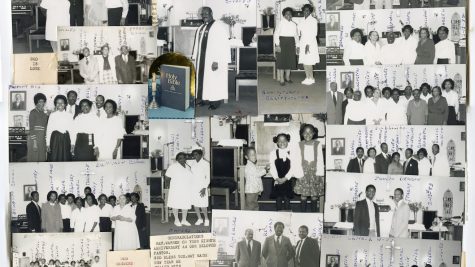

Like the country’s original inhabitants, residents of the former Arthur Capper and Carollsburg community live with their bodies in the present and their hearts in the past. The loss of the community is so relevant to those who were displaced that residents have created a website in homage to the former community. The website features memorials to dead loved ones and remembrances of the community. Some use it to stay connected by posting life updates and planning community day reunions.

“It was historic in itself, but rundown,” said Gairy, who worked in the neighborhood before its transition and has watched it transform. While he felt the neighborhood has lost its character and history, he also conceived that the previous community was too willing to settle for living in depressed conditions.

A similar mindset plagues tribal people who live on reservations. For them, community is more important than condition.

“Shinnecock is about community participation. It’s what sets us apart,” said Terrell Terry, a Tribal Trustee of the Shinnecock Indian Nation in New York.

The tribe’s 1200-acre reservation is all that’s left after 400-years of encroachment by Southampton Town. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, more than 60 percent of Shinnecock citizens live below the national poverty line compared to only 11 percent in the neighboring Southampton Village.

But history dictates that communities that are powerlessly committed as wards of the state have no say in their ultimate fate. According to the 2007 documentary “Chocolate City,” which chronicled the Arthur Gables community at the time of its displacement, one resident said the fine print in the relocation documents said that residents would have to meet 60 percent of DC’s medium income to be eligible for the new low-income housing. However, most residents were working poor and barely met 10 percent.

Although Gairy is impressed with the neighborhood changes, he is disappointed at the city’s tactic of moving the community out to rebuild.

Of the original 707 low-income housing units, only 515 have been replaced in the midst of more than 5,000 mixed-income residential units planned on the Capitol Riverfront. DC Housing Authority blames the recession, but Gairy thinks that it’s all a part of a larger ploy to keep the neighborhood demographics in check.

In 2000, the neighborhood was 54 percent black and 40 percent white. Today, the neighborhood is 55 percent white and 37 percent black. In addition to medium income requirements, strict housing policies that mandate background checks have made it nearly impossible for former residents to reclaim their homes.

Meanwhile, those who are familiar with the former community are left to reconcile its ghosts. For tribal people, this is usually the final stage in the process, otherwise known as forced assimilation. For Gairy, his sentiment reflects the same:

“The sense blackness is gone. I feel like we’re just squeezing in.”