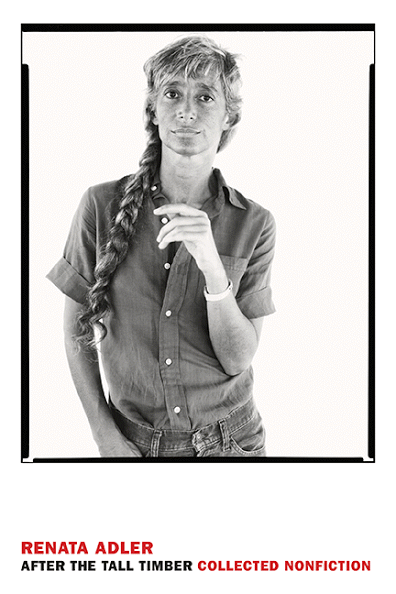

Writer Crush Wednesday: Renata Adler

Renata Adler is the great American author, journalist and critic I have never heard of before. Her novels have a cult following. Her work with The New Yorker over four decades spans reports and essays on civil rights, politics and war, and marked her as a controversial critic of the status quo and of fellow writers. Despite never reading Adler, her impressive bio convinced me to defy a tornado warning to hear her speak at Politics and Prose in April. On April 20, Renata Adler discussed her recently published collection of her past works of nonfiction, “After the Tall Timber.”

Adler took an interesting track at the reading––she did not read from her book. Instead, she shared her current opinions on issues, delivering a “meaningless, rambling” list of her ideas on the world.

She began the “reading” with a discussion on her views on American flags. Placing them on one’s property has become – at least in her view as a citizen of Newtown, Connecticut––not only more common since 9/11––but a symbol of a sad recognition of solidarity in the face of tragedies rather than American triumphs.

Adler explained how she wrote her early, famous nonfiction pieces during times of American optimism, particularly during the Civil Rights Movement. This optimism died out after the movement though, as public figures began to fail and fall, unending wars mired the U.S. in controversy and assassinations and impeachment trials took the country by storm.

She chose to enter into dialogues with her audience, talking with them rather than at them. She admitted that she is embarrassed about how much she loves Edward Snowden. She espoused the improperness of a “swaggering” president. And she shared how scared she is of the fact that if a settled issue, such as abortion rights, can be dragged out from the past, anything can be. An audience member who works with employee rights then responded that LGBTQ people were already losing employee rights, justifying Adler’s fears and epitomizing the open dialogue of the night.

Adler also shared her opinions on writing: “I guess one of the reasons of writing is to try and stay on the page,” she said, regarding her rambling speech at the reading. “If you know the punch line, the whole thing is not to burst it out too early. If I knew the end of the story, why wouldn’t I tell it right away?” she said on how her planned plots crumble as her original story idea changes.

Despite her rambling thoughts, a theme emerged over the course of the night: Where is America going? The America that Adler began reporting on in the 1960s is all but gone; in its place is a land of paranoia, uncertainty and, most importantly, change. Adler’s new collection of nonfiction spans five decades of work in its effort to track how America has changed and what America has become.

Everything Adler said was insightful and scatter-brained and delivered in a voice that, despite her age, rung with cadence and melody. I wanted to know her opinion on everything; despite no previous knowledge of her, I considered her a member of the intelligentsia of the last half of the 20th century. I didn’t agree with everything she said (Why can’t our president have swagger?). But her opinions were unique, informed and interesting. While her current thoughts on society remain rambling rants for the select few who come out during a tornado warning to hear her speak, everyone can read her evolving views on America in “After the Tall Timber.”