The Monumental Past

Monuments have often served as landmarks of historical reference. Though not typically as controversial as the Forrest memorial in Selma, expressing reverence through sculpture and structure has become a hallmark of American historical memory. In the nation’s capital, monuments honoring various significant historical figures and events line streets, parks and traffic circles.

For the most part, memorials attempt to be respectfully didactic. They serve as lessons about the past, items that mark both historical consequence and character. American University’s Student Historical Society president Matthew Skic believes that monuments are important for Americans’ perception of history.

“Historical monuments serve as static reminders of the events and peoples of the past. Commemorating service, sacrifice, and leadership, monuments help to preserve historic memory,” Skic says.

Monuments are a valuable component of public history and help to inform the populace of their forbearers’ contributions to their lives. Dr. Max Friedman, director of the Graduate History Program at AU, says he considers such memorials to be “one of the main ways that the public experiences history.”

“Many Americans never take a college history course or read a scholarly history book, but many visit historic sites, and they can have an enduring impact on what the public learns about the past,” Friedman said.

Professor Kirk Savage, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, is the author of Monument Wars: Washington, DC, the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape.

“I still think that they function as very important, powerful spaces that bring people together, focus their attention, and make them, in some ways, make them feel like they are in the presence of the nation,” he said. In his book, Savage discusses how monuments serve as an “imagined community,” one that helps give the nation a historical identity.

Washington, DC, could be considered a city highly conscious of the past, having received a somewhat unofficial responsibility to represent our nation’s history in its architecture, culture and daily life. Beyond the National Mall, memorials pop up throughout the city. The Women’s Titanic Memorial, located near the waterfront by the Arena Stage, honors those who perished in the disaster. But DC does not simply honor notable Americans or remember exclusively American historical events.

Monuments around the district honor not only lesser-known Americans like John Pershing or Samuel Gompers, but also observe the importance of figures like Mohandas Gandhi and Khalil Gibran. Traditional military veterans are honored throughout the city, but so are groups like Nuns of the Battlefield and Women in Military Service for America. It seems, then, that DC has become an epicenter of memorial, both national and international.

***

Monuments often have unintentional implications that extend beyond serving as history lessons for the passerby. Several complications result from monument building, many of which can do more harm than the good that the memorial intends to convey. The finances behind building monuments sometimes present ethical issues, and perhaps most practically, monuments present a huge monetary undertaking. Friedman points out that these structures are a product of public funding or private donations, both dominated by population of “white male elites.”

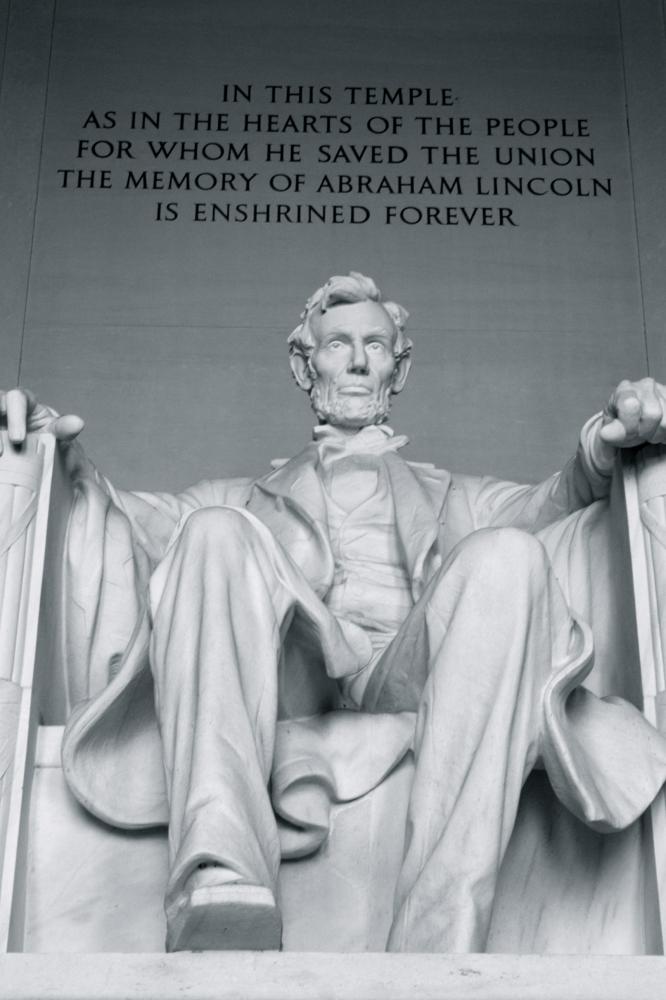

Dedicated in 1922, the Lincoln Memorial cost around $3 million to complete. The Washington Monument, constructed intermittently between 1848 and 1884 cost almost two million dollars, a whopping sum in 1800s America. The high costs of memorial construction call into question the justification of spending so much money on structures meant to honor individuals’ important sacrifices. Memorializing is expensive, and the costs incurred might be better served honoring a cause through contribution rather than through effigy.

The representation of historic figures can also draw controversy. Take, for example, the next big monument scheduled to decorate the National Mall. The Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial, an honorarium to the his life and legacy, will sit across from the National Air and Space Museum, a few blocks from Capitol Hill. The memorial’s website shows how the multifaceted memorial will look to honor his humble origins and the different stages of his military and political life in an effort to “inspire future generations with his devotion to democracy, public service, leadership, and integrity.”

The memorial’s design has met intense criticism from Eisenhower admirers, public historians, and scholars as a misrepresentation of the former President. The proposal seems to characterize Eisenhower as a simple, average American rather than as the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces or the President of the United States. Additionally, Eisenhower’s family considers the museum to be underwhelming and an improper reflection of the President and General’s significant contributions as a public figure. Historians similarly disparaged the Martin Luther King, Jr. memorial, as it seemed to exemplify a personality that was hardly reminiscent of King’s philosophies or persona.

In a lecture to his peers and students in 2012, Professor Michael J. Lewis of Williams College discussed the implications of misrepresenting memory in public monuments, referring specifically to King’s monument.

“Instead of inspiring warmth, there is the infinite aloofness of an idolm,” Lewis said. He considers the monument absent of allusion to King’s actual identity, most blatantly evident in the misquoting of the civil rights leader on the side of his effigy. King never said,“I was drum major for justice, peace and righteousness.” The “quote” was simply a paraphrased reference to something King had heard from another source.

***

Monuments remain fundamentally subjective. No sculptor can appeal to every observer’s historical opinion, but Lewis and others argue that a certain “timelessness” needs to be incorporated into the design process. Lewis argues that in an effort to remain modern and innovative, memorial designers have lost sight of the real purpose of their work.

“A structure that offers a single great lesson is a monument; one that offers many facts and anecdotes is a school or museum,” he said.

If memorials should teach, as Lewis suggests, a single valuable lesson about the monument’s subject, one must wonder what lesson the individual might want displayed. In the end, figures like Martin Luther King, Jr., Dwight D. Eisenhower, and even George Washington or Abraham Lincoln, would probably take issue with their statues and personalities being portrayed for all to see. One can’t help but think that Thomas Jefferson would rather see the time and effort spent toward increasing individual access to liberty than constructing a rotunda to honor his image and legacy. While it hinges on a bit of idealism, the issue can hardly be avoided: how do we justify building grand, expensive structures to men and women who might rather see their work pursued and continued than simply represented by a structure?

Dr. Friedman sees the need for careful production of monuments to ensure accurate representations of historical figures.

“Historical monuments have a tendency toward patriotic fairy tales that are supposed to make Americans feel good by consuming a heroic version of the country’s past,” he said. “It takes a lot of creativity, thoughtfulness, and political struggle to produce monuments that do more than render the official line.”

No doubt the National Mall gives many visitors a feeling of national pride and patriotism. For instance, The World War II Veterans’ Memorial honors each state and territory’s contribution to the war effort. Beyond the circle-structure’s unity, the memorial contains tributes to the industrial contributions to the war, the loss of military lives, and the sacrifice American families made in the name of liberty.

Patriotism is a critical component of this and many other monuments throughout the District. The question becomes, then, should it be? If historical memory is important to monument production, shouldn’t the memorials give us accurate, well-rounded representations of historical figures?

The historical memory may be part of the problem though. There is a significant lack of monuments to political, social and racial minorities in the District of Columbia, as most of the shapers of the early nation were predominantly white males. But monuments to lesser-known figures, especially women and racial minorities, are often tucked away, not displayed proudly around the District’s epicenter like those of Washington, Lincoln and Jefferson. The Mary McLeod Bethune memorial, honoring the legacy of a critical civil rights leader and education reformer, sits in Lincoln Park adjacent to the Emancipation Memorial in a region of the District most tourists will never go.

Yet, it seems unrealistic to scrap monuments altogether. The Washington Monument is not only a symbol of national trial and triumph, but the different gradations in stone color from the halted construction during the Civil War presents a historical narrative itself. Monuments become, inevitably, components of national and public history. They have inherent value as a structure that stands for more than just one person or event.

“Successful historical commemoration usually happens when a groundswell of political participation meets a community demand for using a space and a creative artist is able to translate that rare moment into a compelling physical site,” Friedman said.

Community demand is important, but Skic notes that stressing the “human qualities” of monuments’ subjects is critical.

“Relying on proper historical interpretation rather than myth is what makes a monument effective,” says Skic.

We have great memorials depicting great moments and great figures in history. Perhaps the thing to consider now should not be the importance of producing blind admiration of a certain figure or event, but rather on inspiring informed patriotism. Visitors to the National Mall can be proud to be American without forgetting about the less-than-honorable moments in our history. What makes America is not simply be the glorious contributions from national figures, but also our ability

to overcome tribulation, to unite under astounding pressure, and perhaps most importantly, to recognize errors in judgment in an attempt to progress as a society.

Monuments, then, must be reflective of this all-around history. It should be neither a singular, heroic message that disregards reality nor a confused, ambiguous worshipping of a demigod. Perhaps our monuments should be coupled with funding for institutions that look to advance that individual’s efforts to change society. Sacrifice some pomp for substance, establishing both a passive element to preserving the subject’s historical importance and an active contributions to furthering their legacy.

Even monuments like the Forrest memorial in Selma offer some lessons. Though clearly possessing an offensive character, replacing the Forrest memorial should

not be a way of simply ignoring the undesirable memories from our national past. Remembering Forrest and the KKK is an important part of our national history because if history does not teach lessons about the errors of the past, then it is not serving the population as it should.

“I think in order to make a monument like the Forrest memorial constructive, there has to be a very well-thought-out process of reinterpretation,” University of Pittsburgh Professor Kirk Savage said. “That’s not an easy process because it brings up really strong emotions and a lot of painful history.”

Perhaps it is time to let the American public view history not as something meant to support patriotic generalizations and fervor. Monuments can again be great, but they must focus less on idolatry and more on the educational value history carries for the American people. Hopefully, future memorials will emphasize a holistic view of historical remembrance, reflecting a mature patriotism—one that avoids demagoguery and looks to instigate informed civic action that is both respectful and aware of our nation’s storied past.

Photos by Bailey Edelstein