Stopping Slavery in the Nation's Capital

She cannot go home. She cannot call the police. She cannot tell her friends.

All she can do is wait in fear. The customers will come, and she will do things she has learned to do. The customers will give her money, but she won’t see any of it herself. She is 12 years old; she is a slave.

***

This is everyday life for too many youth in the District. Washington DC has the second highest rating of sex trafficking in the US, right after New York City, according to Deborah Sigmund, founder of Innocents at Risk, an organization based in DC bringing attention to sex trafficking. The group, which works to give a voice to young boys and girls who are trafficked, has found that right here, in the nation’s capital, sex trafficking is a $100 million industry.

Trafficked children are essentially invisible in the US, but some activists are working to change that. This year, DC hosted the Stop Modern Slavery Walk. About 2,000 participants walked to raise awareness about human and sex trafficking, a small amount compared to other walks, like the AIDS Walk, which had around 5,000 participants in the District last year.

“The problem is that we take freedom for granted,” said Ashley Marchand, lead organizer of the Stop Modern Slavery Walk in the District. “In America we assume people have freedom.”

But the issue is steadily gaining visibility. On Sept. 26, President Barack Obama gave a speech on the importance of fighting human trafficking, giving the issue national prominence for the first time.

***

Marchand says the police often fail to investigate cases of sex trafficking and many perceive the girls on the streets to be 25 or 26. But she says many of them are closer to 14.

A big problem in DC with domestic sex trafficking is that, until recently, the local police force has been uneducated about sex trafficking. Detective Thomas Stack from the Montgomery Police Department is a prime example.

He went from knowing almost nothing about sex trafficking to educating police forces across the country.

“Go back 10 years, I didn’t know what it was; I had to be trained. I had to learn,” Detective Stack said.

Until recently, police in the area were uneducated about sex trafficking and perceived it to be prostitution.

Detective Stack said most officers didn’t see sex trafficking as a serious issue. “It’s not Julia Roberts, it’s not Huggy Bear. They had no idea this was going on,” Detective Stack said.

However, Detective Stack has seen improvement from human trafficking and prostitution trainings. He says police forces are quickly learning about the subject and dedicating themselves to the anti-sex trafficking movement. Once the police know, they act.

Organizations like Courtney’s House and Polaris Project have also begun holding human and sex trafficking education seminars for local police. Tina Frundt is the founder of Courtney’s House and says when police aren’t educated about the reality of sex trafficking, girls end up being thrown back on the streets or treated as criminals.

In the past, police treated victims of sex trafficking as criminals and threw them in jail for crimes they were forced to commit. Detective Stack says the situation is improving and police trainings have helped reduce the number of girls and boys seen as criminals.

Detective Stack says that’s only part of the battle: many trafficked children also have an intimate relationship with their pimp. He believes that in order for police to help them, exploited youth have to be willing to trust law enforcement and stand up to their pimp.

“A lot of these girls have been brainwashed to not work with law enforcement; they don’t trust us. They naturally don’t trust the badge,” Detective Stack said.

In order to convict their pimps and get help, trafficked children need to be able to admit they are victims, according to Detective Stack.

“It’s a two-way street; it’s a bond that need to be made, the girls need to trust the police enforcement,” Detective Stack said.

Frundt is a survivor of sex trafficking herself and created Courtney’s House as a safe haven for girls like her. She and the other workers there help guide survivors of sex trafficking. They offer a drop-in-center for survivors to come talk, eat or take any other donated items.

Polaris Project is a national organization dedicated to educating police on the laws and signs of domestic trafficking. They created a national police force, which victims can call toll-free to report their stories. This national police force is trained to understand sex trafficking and not blame young girls for their situation.

***

Sex trafficking is an underground and profitable industry, and particularly prominent in DC due to the transient nature of the city, according to Lindsay Waldrop, an AU alum working for ICF International, an organization working to provide policy solutions for all kids of trafficking.

“With a hidden crime it’s hard to get numbers,” Waldrop said.

In 2011, DC’s National Human Trafficking Resource Center received 376 calls on its hotline. It found 95 cases of human trafficking in DC, 57 of which concerned minors.

ICF International claims diplomats are among the biggest contributors to DC’s human and sex trafficking industry, and one of the main reasons why this problem is so prevalent in DC.

Diplomats have immunity, meaning they have safe passage and are not considered susceptible to a lawsuit or prosecution under the host country’s laws. Although they can be expelled, such action is uncommon for underground crimes such as sex trafficking, according to ICF International. Because of this, diplomats can come from all over the world and bring young boys and girls to be trafficked here in DC without much complaint or problem.

But one of the primary reasons sex trafficking is such a big problem is because it’s easy, according to Sigmund. She says what makes this underground industry different is you don’t need drugs or money.

“To get into human trafficking, you just need a child,” Sigmund said.

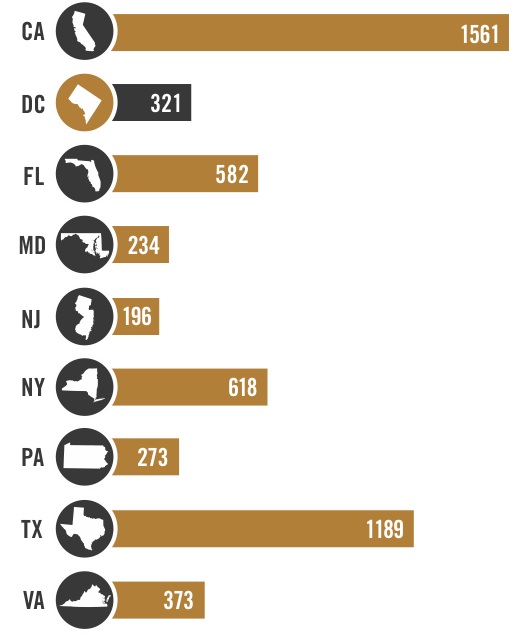

Infographic by Hannah Karl and Julian Morris-Walker.