In the basement of American University’s Hall of Science sits an instrument powerful enough to image the inner workings of a single cell. Right now, logbooks show it’s going unused.

The device is called a transmission electron microscope, and it’s one of the microscopes in AU’s Microscopy Core. Andrea Blake Brothers was responsible for managing the use and upkeep of the microscopes until June, when AU laid her off because of a budget shortage.

Professors and former students said the Microscopy Core has been without an expert manager since then. Brothers, who served as instrument coordinator and Microscopy Core manager from 2019 until this year, said her absence has serious implications for the usability of the microscopes.

“There needs to be someone in charge, because stuff will break,” Brothers said. “It won’t work right, it’ll slowly get worse and no one will notice because it’s gradual.”

Chemistry Professor Shouzhong Zou said he now has been tasked with leading the Microscopy Core on top of his teaching and research responsibilities. He said he knows how to operate the electron microscopes on a basic level, but doesn’t have the breadth of expertise or time required to teach students to use the instruments for varied applications.

“I can understand if you cut some positions, but not some critical positions,” Zou said. “This has a lot of impacts on other people.”

Professors hoping to use the microscopes for research said they now have limited access because of microscopes breaking and the lack of Brothers’ expertise on campus. Students who want to learn to use them are without a mentor, Brothers’ former students said. Science institutions across Washington have lost access to a powerful scientific instrument, Zou said. After AU achieved R1 research institution status this year, professors said the loss of a core research-focused community member feels ironic.

Electron microscopes of this caliber can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. The most advanced microscope AU has, the JEOL JEM-2100Plus, costs around $700,000, according to Rubicon Science and Brothers. Professors said that with Brothers gone, the microscope is not being used.

The university said it cannot comment on individual employment matters.

The shadows of Brothers’ layoff

John Bracht, an associate professor of biology who runs a lab studying evolutionary genomics, said his lab uses electron microscopes and light microscopes. Bracht said using the electron microscopes requires extensive training and, ideally, many years of experience. Brothers said she has been working with microscopes for 50 years.

“That expertise is very hard to replace,” Bracht said. “Also, it’s critical to success, so without someone like Andrea, well, that really hinders us.”

Brothers, Bracht and Jane Bonvallet, a retired metallurgical engineer and microscopist of 30 years, explained the process of electron microscopy to AWOL.

AU’s microscopy core has both light microscopes and electron microscopes, according to the Microscopy Core website. Electron microscopes are the most powerful type of microscopes in existence. AU has many light microscopes and two electron microscopes: a scanning electron microscope and a transmission electron microscope. Instead of using light to create a picture, these two microscopes use electrons.

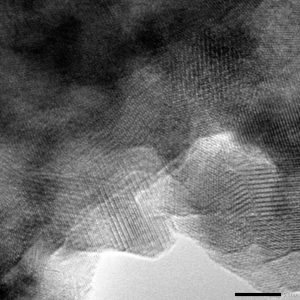

Somewhat like light, electrons act like particles and waves, but their wavelength is much smaller than that of light. This means electron wavelengths allow for far greater resolution at higher magnifications. Electron microscopes enable experts like Brothers to image samples in over a million times magnification. In some cases, it’s possible to see individual atoms.

“Microscopy is, like, the boss,” Brothers said. “It’s the eyes of science, okay? And you can use it as the thing that describes all of science, really. I mean, it’s like, seeing is believing.”

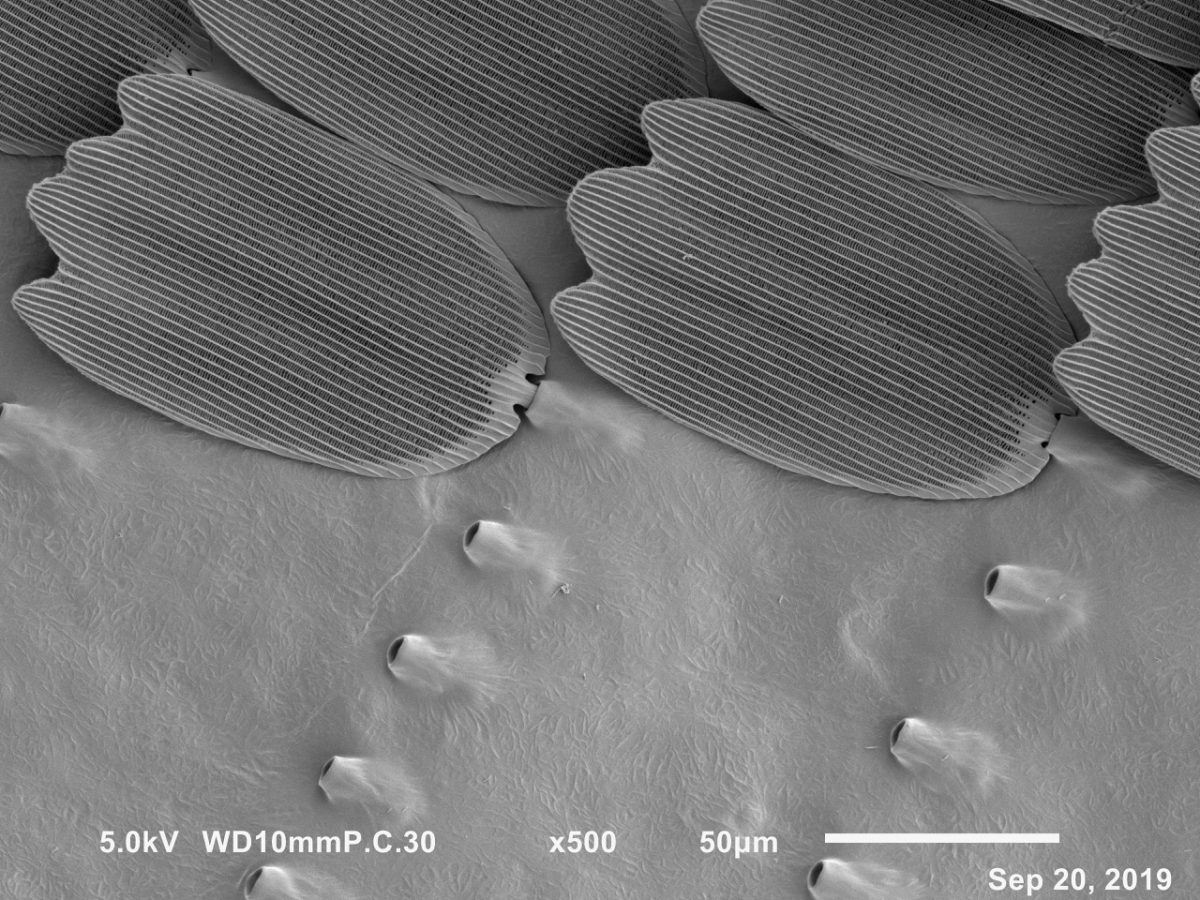

Researchers need to know specialized processes, to use the microscopes, even before they put a sample into them, Brothers said. For the scanning electron microscope, researchers often coat samples with gold to make them more conductive and mitigate a phenomenon called sample charging, which can distort the image. For the transmission electron microscope, researchers must slice samples or apply them so thinly that a diamond knife is often required, Bracht said.

Electron microscopes work by creating an electron beam at the top of a cylindrical column. Electrons extracted from a material called tungsten wire filament pass through a series of electromagnetic lenses, which focus them into a narrow and high-energy beam.

In a scanning electron microscope, that beam passes down through the column and scans the sample. Some electrons from the surface of the sample are knocked off by the beam, and go into detectors, which creates an image.

The more powerful transmission electron microscope works similarly, though scientists must look at an incredibly thin slice of a sample rather than the whole sample itself. Instead of bouncing electron beams off the sample, the transmission electron microscope shoots the electron beam through a sample to the detector underneath. More electrons pass through the less electron-dense parts of the sample and less pass through the more dense areas. This creates a sort of shadow of the sample.

“Basically you are seeing, like, a shadow puppet,” Brothers said.

These microscopes, left without Brothers’ caretaking, are now susceptible to breakage. In her absence, Bracht said one of the light microscopes he uses in his genomics lab has fallen into disrepair.

“Right now, there is no person making sure the other microscopes don’t break down and stuff like that,” Bracht said. “We’re just kind of going on a wing and a prayer that nothing breaks.”

Creating competitive graduates

A key aspect of Brothers’ job was teaching students how to use the microscopes. Passing on that kind of knowledge takes a deep level of understanding of the microscopes, Brothers, Bracht and Zou said. Now, AU students can’t learn to use the electron microscopes to their full capacity, according to students who Brothers taught.

Brothers trained Robyn Alteneder, an AU chemistry student who graduated in 2025, to use the transmission electron microscope while Alteneder was an undergraduate. A large part of the reason she was accepted into Duke University’s Chemistry Ph.D. program was because of this experience, Alteneder, Brothers and Zou said.

“She was recruited because of that expertise that she gained from using the TEM,” Zou said, referring to the transmission electron microscope. “So you can see how this affects our students’ future careers.”

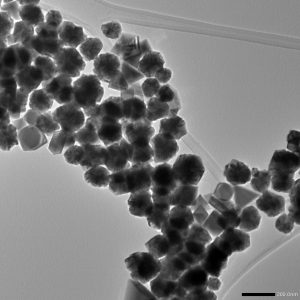

Alteneder said she worked in Zou’s chemistry lab at AU. In the summer after her sophomore year, Brothers taught her how to use the transmission electron microscope. Alteneder said she used it to characterize a type of carbon nanoparticle, or particle between one and 100 nanometers, called a carbon dot.

“It’s also a pretty rare skill for undergrads to have,”Alteneder said. “At most universities, it’s mostly only the grad students learning how to do it, and so I put that in my application.”

Operating the transmission electron microscope is complicated, Alteneder said, so students need guidance and instruction from an expert. Over the course of a year, she said Brothers helped her learn to use the microscope. Alteneder said she doubts she would have been able to learn those skills without Brothers’ guidance and expertise.

“She was very helpful with showing me how to do it first, and then giving me the space to figure it out on my own,” Alteneder said. “Sometimes, she would let me troubleshoot the problem or play around with it for a while to get it to focus and then come in and help when I needed it.”

Ben Wenig, who graduated from AU with a chemistry degree in Spring 2025, said he also learned electron microscopy in AU’s Microscopy Core under Brothers’ instruction. Wenig is now enrolled in a Ph.D. program at Michigan State University. He said the knowledge he gained from Brothers was part of the reason he was accepted there.

“My knowledge of being trained on these instruments and having that experience is part of the reason that I was a competitive candidate, and, you know, was accepted here,” Wenig said. “Having that resource sets AU students apart, right? It makes them more competitive.”

A loss for greater Washington

AU got its two electron microscopes in 2018 as part of a grant from the National Science Foundation and hired Brothers not long after, Brothers said. Zou, the chemistry professor, said he led the original grant proposal.

“It really increased AU’s research infrastructure, right?” Zou said. “And so that was an exciting moment.”

Zou said the grant detailed how the electron microscopes would be vital to AU’s research in multiple departments and the research of the broader science community. Electron microscopes are such specialized instruments that AU’s acquisition of them benefitted researchers throughout the district and attracted attention from nearby institutions, Zou said.

Other institutions, including the Smithsonian Institution, George Mason University and Georgetown University, paid AU to use the microscopes and Brothers’ expertise, Zou said. When these other institutions wrote research papers using the findings from AU’s Microscopy Core, they credited Brothers and AU. Brothers said she is listed on six such papers.

Zou said researchers from other universities cannot use the transmission electron microscope now because it’s too technical for them to operate it without Brothers there.

“We don’t have the TEM expertise on campus anymore,” he said. “So if anyone wants to do that, we just tell them, ‘Sorry we can’t do it.’”

“No point in being in R1”

Brothers’ layoff came about four months after the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education designated AU an R1 research school. The R1 designation is based on the number of doctoral research degrees the university awards and the amount of money spent on research and development, according to the Carnegie Classification. R1 schools also generally have more research resources and capabilities, like a Microscopy Core.

“If there is no support staff, then there’s no point in being in R1,” Wenig said. “If we can’t have an instrument coordinator such as Andrea, we don’t have anybody to keep these instruments running, then we can’t use them.”

Zou and Wenig, the former chemistry student, said the achieving of R1 status and Brothers’ layoff send two very different messages about the status of research at AU.

“I think it’s ironic,” Zou said.

Bracht, the biology professor, said holding on to faculty and resources like Brothers and the microscopes should be at the core of the university’s mission.

“That’s one of the most important long term things we could do as an institution,” Bracht said. “If we want to build our reputation, build student involvement and even enrollments down the line, we need to invest there.”

Edited by Ava Ramsdale, Sydnee Patak, Stevie Rosenfeld, Will Sytsma, Caleb Ogilvie and Kalie Walker.