Student Vets: Wearing the Yellow Ribbon

On December 15 2011, only a speech from Defense Secretary Leon Panetta marked the closing ceremonies of the Iraq War. After eight years and nine months, the war in Iraq has been debated over the course of two presidential elections, resulting in 4,487 US casualties and left 32,226 Americans wounded in action.

One legacy the Iraq War has left behind is the generation of student veterans now attending college in their mid to late twenties. According to the Department of Veteran Affairs, approximately 523,000 veterans were in college in 2008. American University’s number of veterans have doubled since 2009, with over 200 self-identified veterans.

Student veterans at AU receive benefits from the Post 9/11 GI Bill. Introduced by Virginian Sen. Jim Webb, the bill was implemented in August 2009. Until 2011, the Post 9/11 GI Bill completely covered tuition and fees at all in-state universities. As part of the most recent version of the bill, the Department of Veterans Affairs capped aid for private universities, such as AU, at $17,500 per year.

Beginning on January 1, Basic Allowance for Housing stipends, which fund extraneous college costs, are cross-checked with any federal scholarship money. If they do have federal scholarship money, it is deducted from their stipend.

In the fall of 2009, AU began the Yellow Ribbon Program, which covers tuition costs not covered by the GI Bill for student veterans. Institutions such as AU enter into a Yellow Ribbon Agreement with the Department of Veteran Affairs. The University chooses the amount of tuition and fees to contribute, and the Department of Veteran Affairs matches that amount, paying it directly to the institution.

Kamin, a student veteran, calls the Yellow Ribbon “an outstanding achievement for AU and really for the VA.”

AWOL sat down with four student veterans to discuss their life and changes since coming to American University. Here are their stories:

Rob Peavey – An Iraq Veteran by Chance

Rob Peavey, a film major focusing on documentary film-making, joined the Army in June 1997. He was 17 when he signed the initial contract and 18 when he went to basic training. He is tall, with a beard and brown eyes. His speech is soft and clear.

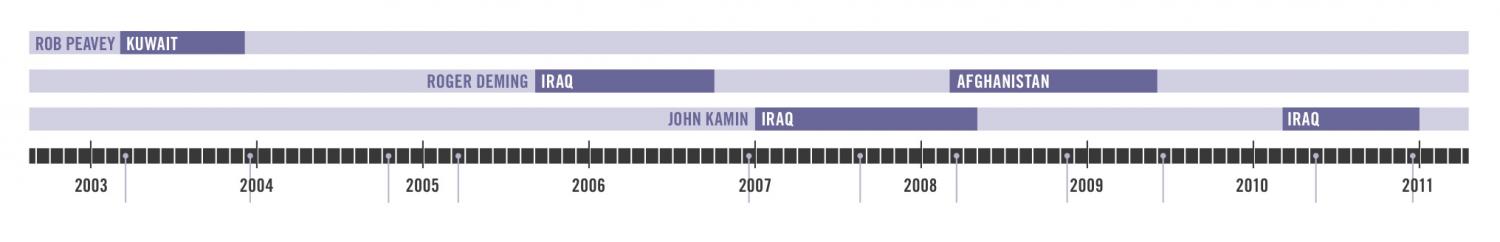

For the first six months of the Iraq War, he spent time in Hawaii, Korea, Fort Bliss, and finally Kuwait. Peavey was in Fort Bliss when the Twin Towers were hit. His base immediately went on high alert.

“I think the majority of the soldiers were ready to go to Afghanistan,” he said. “But then a few days when our brigade commander briefed us, he said ‘We can’t send everyone, we gotta stay here,’” he described. “I think that was so they could prepare us for invading Iraq. I think that’s why we had to stay behind, we couldn’t all go to Afghanistan.”

Peavey was an individual augmentee, which means he was assigned to units when needed. He was sent to Iraq for six months until his contract expired. While in Iraq, he didn’t see much combat.

“The only real combat I saw was when the war started. It was only the first week; they were firing missiles at us,” Peavey explains. “They were all shot out of the sky or misfires. This one day was really, the explosions were real close. I was about to fall asleep and the explosions happened. Then we found out the sky missiles were directed towards a building I worked at where all the generals were.”

“So that was exciting,” Peavey said. “For about a week I didn’t really get much sleep, but after that it was just,” Peavey paused. “Boredom.”

While he didn’t see much combat, the war in Iraq made the veteran more anti-war.

“When I was in the military, I thought like all the other soldiers, I was defending our freedom. But when I got out, I realized that we really aren’t,” Peavey said. “We start all these wars—it made me realize I became a bigger advocate of anti-war movement.”

Peavey got back from his service in Kuwait and went through reintegration training before returning back to his small town in Tennessee.

“After two years of dead end jobs I realized I needed more than an Army education,” he said.

He decided to attend community college for an associate’s degree and joined Phi Theta Kappa, the international honors society that focuses on two year colleges.

“I got an email from American University and they were looking for PTK students and I noticed they had a decent film school,” he said. “So I applied. It was the only school ever I applied to, and they accepted me.”

Peavey says coming to AU was his only path, and he wouldn’t have been able to do it without the Post 9/11 GI Bill.

Roger Deming – The Face of AU Vets

Roger Deming is accustomed to juggling commitments. He became the president of Student Veterans of America at AU in the fall and has been a student government class senator for two years.

During his active duty, which lasted from 2004 until 2009, he went on two separate tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. His return from Iraq was easier than his transition coming home from Afghanistan.

“I was coming back with guys who were going through the same thing,” said Deming of his experience in Iraq. Because he was still active duty, his life was more or less the same. “With Afghanistan, I was actually pretty busy prepping to get ready for college,” he said.

Deming chose DC for the same reason most choose DC: politics. Prior to joining the military, Deming was enrolled at Clarkson University, before transferring to Cornell University.

“I wasn’t prepared for the environment I was in,” Deming said. “I did ROTC in college, and I found myself realizing the only thing I tried to prepare for or look forward to was the ROTC stuff I do.”

Looking back, Deming said he should have recognized this earlier. “Shouldn’t have wasted so much of my parents’ money,” he said with a chuckle. “And realized I needed the Army as much as they needed me.”

Deming found the same sentiment at AU through the veterans coordinator, who connected him with the new veterans group. He ended up in a house full of other veterans, where he has been living since he transferred.

When he first attended AU, he was not receiving the money for the Post 9/11 GI Bill, because he was only attending the University part time. By his second semester, he was able to use his GI benefits, but could not collect money for the Yellow Ribbon program.

The Yellow Ribbon program at AU has a three week application window. Deming described this as especially difficult for first year transfer students, as well as prospective students overseas. “There’s been people like me who qualify, but because it was the first year here at AU, we didn’t know how the system worked.”

By the second academic year, Deming and most other veterans he has met were able to receive the full benefits of the Yellow Ribbon program. “Right now, AU has done a tremendous job where anyone who has managed to apply for the Yellow Ribbon, they’ve been able to cover,” Deming said.

“A lot of what I see is that the administration wants to help—they’re just not always sure how,” Deming said. He thinks a big part of that is what we see in society. He explained the problem as a disconnect between the most recent generation of veterans and the few who served in combat in the 30 year gap after the Vietnam War.

Deming hopes that when the current generation of veterans are older there will be a shift in attitude about the mental stability and hiring potential of veterans.

“But by then there might have been 15 years of no military conflict in the US, so there’s not going to be a whole bunch of veterans that need help,” he said.

John Kamin – The Veteran Who Advocates

“I think every boy at some time in their life imagines themselves as something great,” John Kamin explained over coffee. For Kamin, it was becoming a soldier.

For the New York native, Hofstra University made the most sense as a college choice. “I had gone to college because that’s what all my other high school friends were doing, and that’s what my parents wanted me to do,” he said. “But I didn’t really understand why I was doing it, and after the first year, I didn’t really want to do it anymore.” He enlisted in 2005, at the age of 20, and chose the Army.

Kamin did one tour in Iraq and was honorably discharged in 2008—making the choice to go back to Hofstra University for another two semesters. “It was like my first time, only I was a little older, a little more mature,” said Kamin.

The second time around, Hofstra University was easier than the first, almost too easy. So Kamin decided to challenge himself, applying to Columbia, Duke, Vanderbilt and American University. “I was really blown away by the environment,” said Kamin of AU. “It was the only thing that really clicked.”

At AU, Kamin immediately joined AU Vets and held an internship where he could advocate for veterans. Kamin explained his internship helped him be more comfortable with his identity as a veteran.

“It was the first time I realized I could still,” he struggled to find the words. “That this was still part of my identity outside of the military. That it wasn’t anything I had to hide, or only mention at parties, or not to wear on my sleeve, but that you shouldn’t run away from what you did.”

Kamin has found a feeling of community among other veterans. He remembers going to a nightclub in Savannah his third night out after coming back from Iraq. “I’m not really into it, I don’t like nightclubs anyway, especially then,” he explained. “I was passing by someone in the hallway by the bathroom and I say, ‘You look really familiar. Were you in 269 Infantry, 369 Armor, I think?’ and he was like ‘Yeah yeah yeah, what’s up man?’ And I asked ‘Did you just get back here too?’ and he said, ‘Yeah it kind of sucks, right?’ Just kind of having those kind of connections where you have someone who you immediately think of as a friend, someone who is close to you.”

His identity has become more shaped by the military as he has continued his college career. It became abundantly clear he couldn’t forget when the Army recalled him for a second tour in Iraq. At that time, the Post 9/11 GI Bill was just being implemented, but had problems in its first semester.

“Very few of us got paid the first semester or got money that would pay for school,” said Kamin. “It’s funny, I got my first check from the VA on January 18, which was my second day back in the Army, so it was like ‘Thanks a lot,’” he said with a chuckle. His second tour lasted nine months, and he had only a few weeks before going back to school.

Kamin was elected as president of AU Vets in the spring of 2011. He was also asked to run for president of the national branch of Student Veterans of America, but lost. Kamin is currently interning at the Student Veterans of America and, in his free time, is in the process of setting up a group for American University veteran alumni.

“There’s a natural component of being quiet and reserved and humble about your service that 99.9% of all veterans I’ve met share,” said Kamin. “It ain’t ever going to be like a fraternity where you can just wear your letters—that’s not the way veterans do things. You owe it to your friends that are still in the service, you owe it to friends you may have lost to not prattle about your exploits.”

Daniel Feeman – The Veteran Who Missed the War

Daniel Feeman comes from a military family. His father was in the Marines and so are two of his brothers. Like many other student veterans, Feeman went to college before enlisting. He was unenthusiastic about attending North Seattle Community College. He was on a partial lacrosse scholarship at the time and didn’t care enough about his grades.

Feeman decided to make a change. He enlisted in the Marine Corps on a Friday and left the next Sunday. He was active duty for five years, during the most lethal time of both the wars. From 2005 – 2007, 2,879 men and women died in either Iraq or Afghanistan, according to The Washington Post’s Faces of the Fallen, a photo database of American soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Military police at that point had five year contracts because the route security in Iraq was getting blown up on a daily basis, and they needed guys to stay in,” Feeman explained. “There was a level of expectation there—my level of expectation was that I would finish MP [military police] school and end up doing route security in either Iraq or Afghanistan.”

Feeman finished high in his military police class and won the opportunity to go to military working dog school. His goal was to go into a program that hunted bomb-makers with dogs.

“In hindsight, I’m really glad I didn’t do it,” he said. “They ended up with the nickname sniper bait.”

While he was there, a recruiter from Marine Corps One had a meeting looking for men and women to work in the White House Military Office. Feeman had no interest in the meeting and instead was on barracks duty.

“He met me, and to quote him, he ‘liked the cut of my jib’ and asked me why I hadn’t applied for it,” Feeman explained. “I said because I wanted to go to Afghanistan…and he went ‘I’ll tell you what, if you put in an application with me and I can’t take you or you really don’t want to do it, I’ll frontline you for the program.’”

Feeman signed the paperwork only to find out a few months later the recruiter never had the intention of putting him into the program that hunted bombs. “He was like ‘Believe me, you don’t believe it now, but in a couple years, you’ll figure out that I did you the biggest favor you’ve ever had,’” Feeman said. “And he’s right, completely.”

He had the opportunity to work for two presidents and went to 22 countries in his time at the White House Military Office. When it came time to apply to college, American University was the only one who offered the full Yellow Ribbon Program.

“Georgetown offered me a full thousand dollars and I was like, ‘No thank you,’” he explained jovially. “That was the whole reason I went to AU, because they did the full Yellow.”

At American, Feeman sometimes found it difficult to relate to the idealism of doe-eyed college students. “The Marine Corps is really good at ruining whatever ideology you have that the world can be fixed in any way,” Feeman said. “You’re not very optimistic by nature.”

Feeman graduated from American in December, one year and 11 months after he began. He did so by taking more than a full class schedule and adding on summer classes. He called himself an absentee member of AU Vets and just joined the National Association of Uniformed Service, which works to maintain military rights.

Feeman admits he was lucky to get a job at the White House Military Office. “He wouldn’t have met me if I hadn’t been on barracks duty, which was a completely random happenstance. So it’s both lucky and what it is,” Feeman said. “People taking care of you and being good at what you do.”

Photos by Claire Dapkiewicz and Daniel Feeman.