Rhema Jordan Labbe entered the world of pour-over coffee in her college dorm room. Then a sophomore at Muhlenberg College, she ordered a Chemex, a grinder and some beans and began serving cups to her roommates. For Labbe, brewing in her dorm was a form of meditation, a slowdown from the hustle of college life.

When the pandemic hit, Labbe was back in their birthplace, Washington, D.C., and rediscovered coffee as a tool for connecting people through shared experiences. They started Roots&Rivers in 2020, a curated coffee space and pop-up studio. Labbe said their approach is rooted in observations they made during an artist residency in Japan, from the slowness and intentionality of the brew to the ceramic she presents drinks in.

“For me, coffee has always been a ritual and an experience, and one that kind of creates space for people to connect,” Labbe, who uses she/they pronouns, said.

When Roots&Rivers first popped up with a folding table outside of a Petworth flower shop, Labbe didn’t advertise beyond word of mouth. Since then, the pop-up has moved into Labbe’s personal studio and hosts monthly gatherings to share coffee and art. Throughout its lifespan, Roots&Rivers derives from Labbe’s work as an experiential artist and is an ode to three things, she said: coffee, design and collective expression.

“My hope is that Roots&Rivers brings a space that feels like an extension of home to folks, and that provides a level of comfort, stillness and creative inspiration, creative integrity, to people’s spheres,” Labbe said.

For Labbe and other curators of creative coffee spaces, profit isn’t a priority — the people and the creative expression are. The ritual of coffee is important to Roots&Rivers, Labbe said.

“It’s a process that people are able to see into and participate in and engage in, as opposed to, like, an order’s taken and then I’m going elsewhere to prepare it and then bringing it back,” they said. “It’s important to me that everything’s kind of between myself and the guest.”

Around Washington, owners of coffee pop-ups and independent cafes said they are bringing a new emphasis on creativity and community to the district’s coffee scene. Shops like these belong to a trend called third-wave coffee, a new coffee movement with a people-first approach differing from the profit-driven practices of chain cafes, according to Labbe and other owners of small coffee-centered spaces. Third-wave, owners around the district said, is still getting off the ground.

The district’s specialty coffee scene emerged in the 2010s after local chains like Compass Coffee brought a greater attention to detail into coffee, said Antonia Petaccio, a coffee educator at a multi-unit cafe in Washington. From the late 2010s into the COVID-19 pandemic, a shift toward independent third-wave shops took place, Petaccio said.

Coffee in the 1900s used pre-ground and mass-produced beans that were often bought in grocery stores, according to an article on the evolution of coffee by Press Coffee, an Arizona cafe and roastery. In the 1960s and ‘70s, as part of the second wave, chains and espresso drinks like lattes and cappuccinos became more popular, according to the article.

In the late 1970s and ‘80s, Boston roaster George Howell started a third wave of coffee by inspiring people to pay more attention to the quality of beans, according to a 2012 Boston Magazine article. Specialty coffee — attentiveness to the quality of beans — has remained an essential part of the third-wave movement.

In Washington, Petaccio said the third-wave scene is a way for people to offset the gloomy political atmosphere that can hang over the city. Politics, she said, isn’t the only culture of the district.

“There’s a huge need for spaces, for people to gather, to not have anything to do with all the political prattle that is kind of happening downtown,” Petaccio said. “And from what I’ve at least learned through living here is that it’s a hugely, hugely, like, creative-based city.”

Being a third space — a place of socializing and community outside of home and work — is central to the ideas behind Roots&Rivers, Black Crown Collective and Shaw-based Little Hat Coffee, according to their respective owners.

Petaccio said Little Hat, an Asian and Hispanic-owned third-wave shop, has fostered an authentic community with little space.

“[They’re] in a really, really teeny-tiny corner with, like, four bar stools, and their community that they’ve built is like it’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen,” she said. “They have just done a really, really impressive job at being their authentic selves and kind of incorporating everybody who walks into the Streets Market into their little world of coffee.”

Francisco Contreras, co-owner of Little Hat, was drawn into the coffee industry by the people. He said he didn’t even like drinking coffee when he began working at Compass Coffee, but the community that surrounded coffee enticed him.

“It’s the people that care about the coffee that really makes the coffee stand out,” Contreras said.

Little Hat began as a pop-up, collaborating with spaces like the Grand Duchess, an Adams-Morgan bar, to push product. Now based out of Streets Market near the U-Street Corridor, Contreras said it aims to be approachable and easy-going.

After moving into Streets Market in October 2024, Contreras said Little Hat has developed its own unique community.

“It really has become a third space, even though it’s like 300 square feet inside of a supermarket,” he said. “It’s a very unique experience in terms of, like, what’s out there right now in the city.”

He said there was a point where he wanted Little Hat to be just a milk and espresso operation — nothing flashy. Though what they serve has moved past that, serving matcha and sweetened drinks, Contreras said they still maintain their down-to-earth style.

“I feel like we’re more ratchet, or just, like, we’re not really thinking about how we appear,” he said. “That’s just a different style. I’m not saying one is better than the other. I just feel like we’re kind of just winging it half the time.”

Little Hat wants to be advertised by word of mouth, Contreras said. He said he hopes people will bring a friend who might be pleasantly surprised by Little Hat’s product with no prior expectations. Talking to people, Contreras said, is the joy of the business.

“We’re so small that every cup means everything to us,” he said “So we try really, really hard. And I would hope that this is like the case for other businesses in the area or other coffee shops. But honestly, we’re just trying to meet people.”

Petaccio said coffee concept owners don’t need a brick-and-mortar to create community, either.

For Black Crown Collective, a pop-up, education is key to third-wave and fostering community. Co-owner Drago Tomianovic said he works to expand people’s ideas of what coffee is and the way it can express itself. Coffee is not, as many people assume, a monolith, he said.

“Coffee can be so many different things depending on how you know what variety you’re getting, what species you’re getting, how you’re brewing it,” he said.

Co-owner Sam Deur said the two aim to teach with a “non-aggressive” and “non-pretentious” attitude. Some people come to their events without knowing anything about specialty coffee, she said, and she’s always happy to answer their questions about sourcing and equipment.

“For both the public and the private events, it’s really fun to just offer a space where, if people want to learn, they can in a way that’s really friendly and engaging, and that is hugely fulfilling to us as well,” Deur said.

Tomianovic met Deur, his self-described partner in life and business, because they both wore tattoos of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s crown motif. In 2023, the two started Black Crown Collective as a passion project to let their creativity loose through coffee.

Deur said their connection to Washington’s art community has informed their business model. Many of their coffee pop-up events collaborate with other art-centered businesses, like art galleries and vintage boutiques.

“We wanted to build this, in a way, as an homage to the community that we love, and the local community specifically,” Deur said.

Commodity coffee chains may be serving the same product as third-wave cafes at a glance, but Tomianovic said the third-wave movement is almost a different industry entirely. He said second-wave chains like Peet’s and Compass’ goals differ from third-wave shops.

“Those are very high margin, focused on just mass numbers, and there’s not, like, a real human aspect to it,” he said. “Which is not a bad thing, it’s just a very different approach to coffee.”

Peet’s and Compass Coffee did not respond to requests for comment.

To be third-wave means putting time into the drinks, said Carlos Arana, a barista who became a self-described “coffee snob” after starting to work at The Coffee Bar. From the espresso extraction to the amount of ice in the drink, he said third-wave infuses care into the craft.

“Those [shops] are the places that take the time out to create a pullover, or take the time out to perfectly extract the single origin espresso,” Arana said.

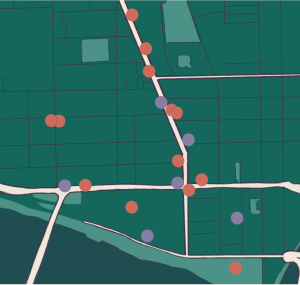

Petaccio said there are a lot of different expressions of coffee around the district, but the creative coffee scene is more buried than in places like New York City. The absence of third-wave cafes requires coffee drinkers to seek out more pop-up events.

“The everyday consumer does have to put a little bit more effort into seeking out those places,” she said. “And also, there’s, I think, a little bit more of reliance on word of mouth to hear about these different kinds of expressions and specialty coffee.”

The third-wave scene is developing and chains saturate the streets, so customers have less choice of where they drink, Petaccio said.

Cafe culture in Washington varies by neighborhood. Of the 18 shops that appear in a Google Maps search for cafes near the Shaw and Logan Circle area of the district — home to Little Hat and The Coffee Bar — nine are local, independently-owned businesses. In Georgetown, only six of 19 are local businesses.

Large second-wave businesses dominate Washington’s caffeine culture by the numbers. There are 91 Starbucks locations across the district, according to the World Population Review. Compass Coffee has 23 shops across the metro area, according to its website.

Petaccio said chains are contributing to a “cookie-cutter expression” of coffee, bringing lackluster experiences where smaller shops could bring authenticity.

“There’s still so much room for more, and I wish that there was maybe a little bit less of the multi-unit sort of iterations of coffee that are not necessarily doing their coffee its justice or aren’t necessarily showcasing specialty coffee or third wave coffee in the same way that these smaller specialty, like, craft businesses are doing,” Petaccio said.

Contreras said chain cafes are pricing out local culture. Chain businesses move into communities and undercut mom and pop shops that can’t afford the slim profit margins, he said.

“I think, again, people are priced out, and that goes with coffee and food and restaurants,” he said. “You don’t have those really small, immigrant-owned or family-owned spots, with the exception of those that have already survived 10 years of the city.”

But Contreras said he understands why chains follow the model they do. It comes down to the city’s coffee culture — some people aren’t willing to pay a high price for their brew.

“People are not willing to pay for coffee, right? Compared to alcohol or food,” he said. “Even though the same amount of work and, you know, logistics and skill goes into this cup of coffee.”

But Arana, who didn’t find specialty coffee until 2020, said he’s seen a lot of young people start to come to specialty coffee. He said earlier in his 20s, chains were the cafes of choice for many people his age.

“But now at The Coffee Bar, I see more and more young people coming to get drinks without sugar, coming to get just like lattes or flat whites or cappuccinos,” Arana said.

Washington’s coffee drinkers can get excited for the next decade, Tomianovic said — there’s a lot of opportunity for growth. For newer shops coming to the district, Contreras said he hopes their priority remains with the people they serve.

“I hope that people don’t get lost in the numbers,” Contreras said. “And I hope that their priority’s still people and coffee, because that’s the whole point of it.”

This article was originally published in Issue 36 of AWOL’s magazine on April 15, 2025. You can see the rest of the issue here.

Editing by Bailey Bish, Ava Ramsdale, Julia Cucchiara, Ben Austin, Kalie Walker, Stella Camerlengo, Caleb Ogilvie, Grace Hagerman and Alexia Partouche.