Sophia Joseph, a senior at American University, published an open letter on Sept. 17, 2024, responding to an Instagram post by the American University College Republicans.

The AUCR Instagram post said, “Trump will save the kittens and ducks!” referring to then-presidential candidate Donald Trump reiterating false claims that Haitian Americans in Springfield, Illinois were eating pets.

In her letter, which she posted on her personal Instagram account, Joseph said Trump’s comments led to an influx of violence towards Haitian Americans and that AU College Republicans’ post about Trump’s comments heightened her fears.

“For the first time, as a Haitian American, I find myself frightened,” Joseph said in the open letter, which is no longer on her Instagram account.

Like Joseph, many students across Washington have experienced heightened tensions as a result of politics being increasingly present in social media. Some say this has made them feel unsafe in their day-to-day lives and has created divisions between their peers.

The criticism wasn’t new for AU College Republicans. Joel Pritikin, the club’s president, said students often express dislike for the organization because of its political affiliation.

“It doesn’t matter what we are or how we portray ourselves,” Pritikin said. “Just the ‘R’ next to our name is what gets us hate. And you can say that’s unfair, but you know, this campus being mostly Democrat, it’s the preconceived notion of what they’re going to think of us.”

When asked about Joseph’s open letter, Pritikin said, “We don’t care. That’s our comment.”

He said the club is within its rights to post online about politics and claimed Joseph published her open letter to gain popularity and help her run for an AU Student Government position.

“It was never about winning AUSG,” Joseph said. “It was about the fact that rhetoric like this harms people.”

James Cox, a sophomore who is also a member of AU College Republicans, said he tries to avoid online arguments about politics, as he believes they are unproductive. He said he will participate if something online strikes him, though.

On Feb. 14, the @stoolamerican Instagram account, a popular Instagram page for AU students, posted a photo of an individual on campus who appeared to be a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officer. Cox left a comment in support of the alleged ICE officer: “We’re so back.”

“I’ve expressed my opinions and beliefs and received comments and direct messages on social media,” Cox said. “Some never really try to engage with the ideas I’ve expressed publicly, but rather insult me, which is unfortunate.”

Emma Sprung, deputy director for AU College Democrats, said members of her organization also experienced increased political tensions when they participated in phone banking during election season. Many voters they spoke with claimed political information was fake news, making it hard to have a conversation about political topics. Sprung said this often leads to hateful discourse about politics.

“The amount of misinformation and disinformation that’s out there and the amount of fearmongering on both sides of the aisle is terrifying,” Sprung said. “It’s not only disheartening and discouraging, but it’s scary.”

Sprung said AU College Democrats has also witnessed negativity and misinformation on websites related to AU. She believes some users use their platforms for hate or aim to start fights in comment sections. These fights often divide students.

“Just in general, if you go to the comments on any social media, there’s almost always hate and some type of discouraging comments,” Sprung said. “They are just not promoting a welcoming environment. And there’s been moments when I know that myself and other people have not felt welcomed or like safe on campus. And that’s not because of physical acts, but because of what people are saying online.”

Less than a quarter of students surveyed by the Knight Foundation said they believed dialogue on social media is usually civil, according to a 2024 study by the nonprofit journalism group. That’s compared to 40% in 2016, when the survey was first conducted. Additionally, the 2024 study found that 78% of college students from around the U.S. feel it is too easy for people to say things anonymously online.

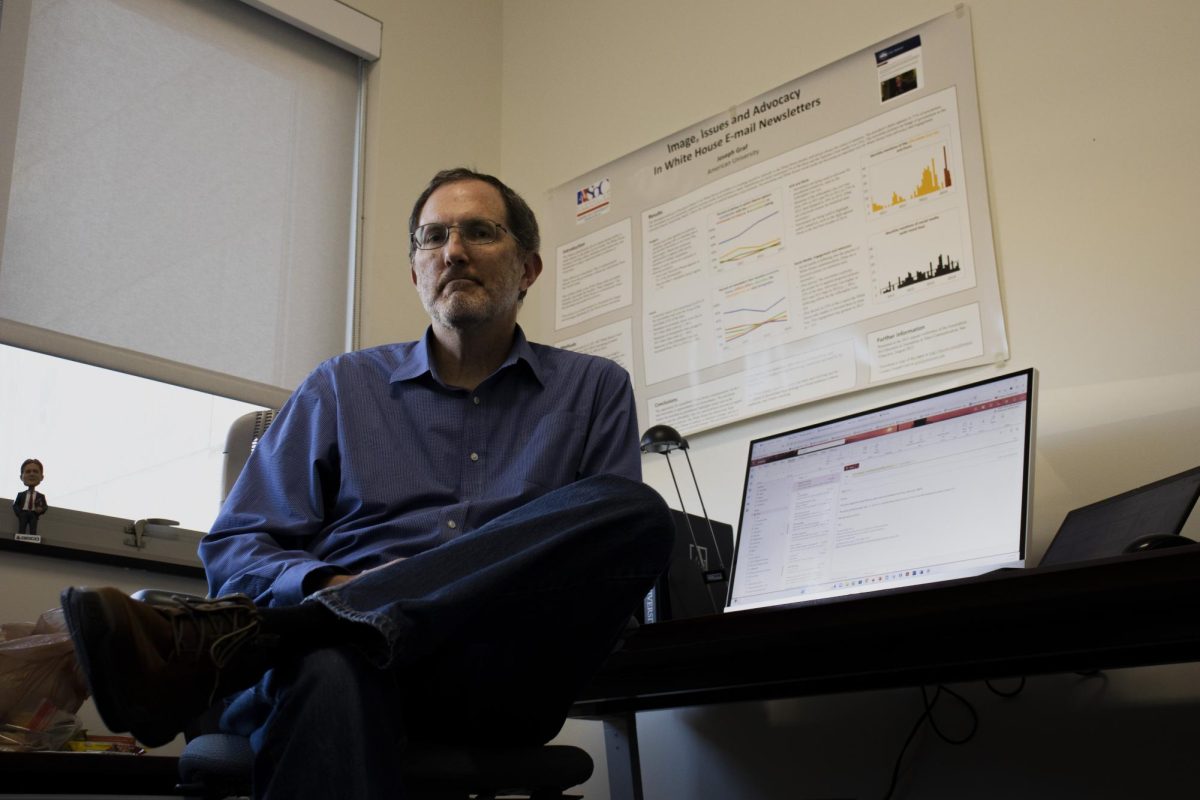

Joseph Graf, a senior professorial lecturer of political communications at AU, said the algorithms of social media apps are designed to reinforce pre-existing political beliefs. He said this is often apparent when constituents use social media to support politicians or political parties.

“I think that TikTok is a way to display your energy for a candidate or a campaign,” Graf said. “But the problem is that the people watching that video probably already agree with it, and consequently, I’m not certain that it’s changing many opinions.”

Paul Barrett, the deputy director of the Center for Business and Human Rights at New York University’s Stern School of Business, also said social media algorithms aim to show users information they will engage with.

“What we’ve learned over time is that users of social media are more likely to engage with material that’s sensational or seems novel, new, different,” Barrett said.“That’s likely to provoke an emotional reaction, particularly negative emotional reactions: anger, frustration, being upset about it.”

Barrett said this kind of material is likely to be false and divisive. It’s also likely to reinforce people’s preexisting beliefs and contribute to political polarization, he said.

“You have a fire that’s already burning,” Barrett said. “Divisiveness, political polarization — and social media is like gasoline that you pour on the fire. It didn’t start the fire in the first instance, but it intensifies or heightens the fire.”

That intensity is especially likely to increase among people with right-wing political beliefs, according to Barrett.

“Democrats and Republicans are both prone to saying things that are inaccurate, but when it comes to this extreme polarization and extreme proclivity for distortion of just what reality is, that’s happening more on the right than it is on the left,” Barrett said.

Abby Morin, a sophomore at AU, said talking about politics on social media is unproductive because users are divided and don’t want to listen to opposing viewpoints. She said when she posts about politics on social media, people respond with arguments.

“I often post political stuff, or make it very clear where I stand on politics, and then I’ll have people respond and argue with me about that on dating apps and Instagram,” she said.

Sol Garrido, a sophomore at George Washington University, said political content online can also bridge the gap between communities. Garrido, who serves as the public relations executive board member for GW’s Puerto Rican Student Association, said Puerto Rico came into the spotlight on social media after comedian Tony Hinchcliffe referred to the country as a “floating island of garbage” at a Trump-Vance rally last October at Madison Square Garden.

“Everyone I know from Puerto Rico, including myself, has been posting pictures of how pretty Puerto Rico is and being like, ‘Do you call this trash? Does this look like trash to you?’” Garrido said.

Garrido said she believes Hinchcliffe’s joke was hurtful but brought attention to Puerto Rico and led to people being more informed about the island. She said it wasn’t good, but did bring some people together.

Ronan Tanona, a sophomore at AU, said talking about politics online has exposed him to people who have different beliefs than his own. He said he is often surrounded by people who might align with his beliefs.

“So, online actually provides a space where I can interact with more people who have different opinions than me,” Tanona said.

He said those interactions don’t usually affect his life outside of social media. However, his offline life does impact his online activity.

“What happens in my day-to-day life impacts my participation in political discourse online because that is stemming from a place of what I see in real life, what I care about in real life and what I’m doing in real life,” Tanona said.

Graf, the senior professorial lecturer, also said politics on social media may have positive effects. He said social media is a new avenue for young people to participate in politics. Although he said he wasn’t sure about the effects of TikTok, he pointed to campaigns and political involvement as areas where social media could have an impact.

“It is a kind of political engagement that we have to take seriously, and we didn’t for a long time,” Graf said.

After Joseph criticized AU College Republicans on social media, Pritikin said members of the club have remained steadfast in their beliefs.

“We always get drama surrounding us,” he said. “We stand for everything the average AU student stands against. It’s what we are.”

Meanwhile, Sprung said people have continued to respond to AU College Democrats’ political postings negatively. She said it’s much harder for the club to address disparaging comments when their users are anonymous.

“You don’t know who’s posting these things,” Sprung said. “They’re hiding behind a screen. And these people see you, know you, and they post these things about you, and you don’t know who it is. That’s the scary thing about social media.”

Editing by Ava Ramsdale, Caleb Ogilvie, Grace Hagerman and Alexia Partouche.