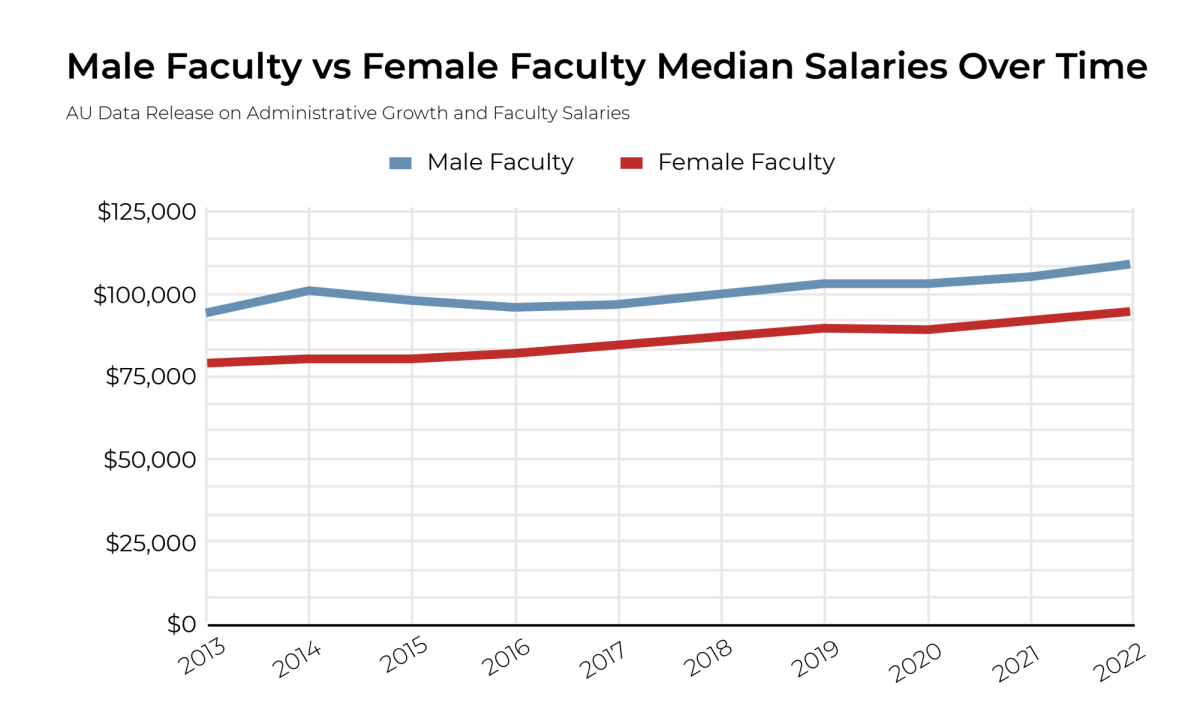

Male faculty are paid more on average than female faculty at American University, according to data released by the provost’s office in September 2023. A significant portion of the gap is due to men holding senior, higher-paying, professorial positions at higher rates than women.

Wage gaps between male and female faculty exist across the United States. However, the data released in September 2023 provides a glimpse into the gap at AU.

The median salary for male faculty was $13,900 more than the median salary for female faculty in 2022, according to the September 2023 dataset, which included faculty salary data from 2013-2022. Median salary difference may provide a more accurate view of the gap, as it is less likely to be affected by highly paid “star professors,” said Glenn Colby, a senior researcher for the American Association of University

Professors, a nonprofit faculty association. On average, AU paid male faculty $16,182 more than female faculty in 2022.

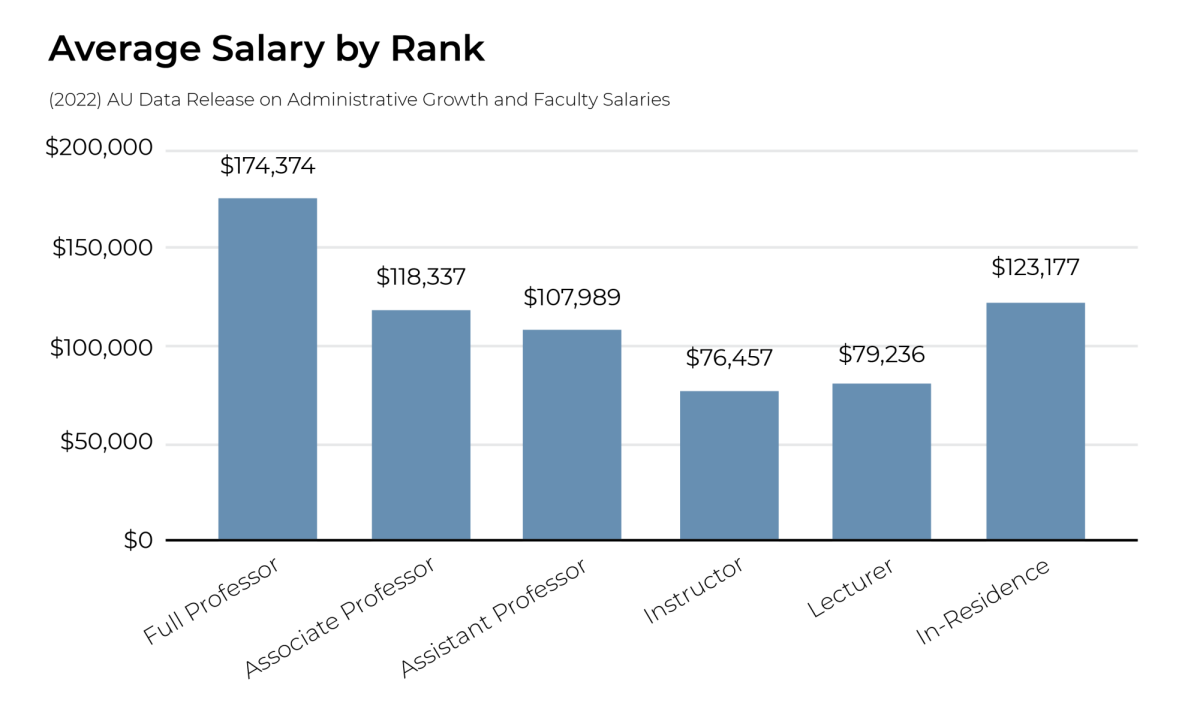

The disparity in pay is partially driven by disparities in faculty rank and discipline. Faculty — the academic staff — at AU can be broken down into several ranks. According to the AU Faculty Manual, instructors and lecturers hold one-semester or one-year appointments and fill specific temporary teaching positions.

In contrast to the short appointments of lecturers and instructors, faculty on the professor track methodically climb the ranks at AU. Professorial positions, in ascending order by rank, include assistant professors, associate professors and full professors (often referred to

just as “professors”). After six years, assistant professors who meet the criteria for associate professor, usually tenure, can apply for a promotion to that rank. An associate professor may undergo professional review to become a full professor.

Higher professorial ranks are paid more on average. In 2022, the average salary for a full professor at AU was $174,374. That’s $56,037 more than the average associate professor that year.

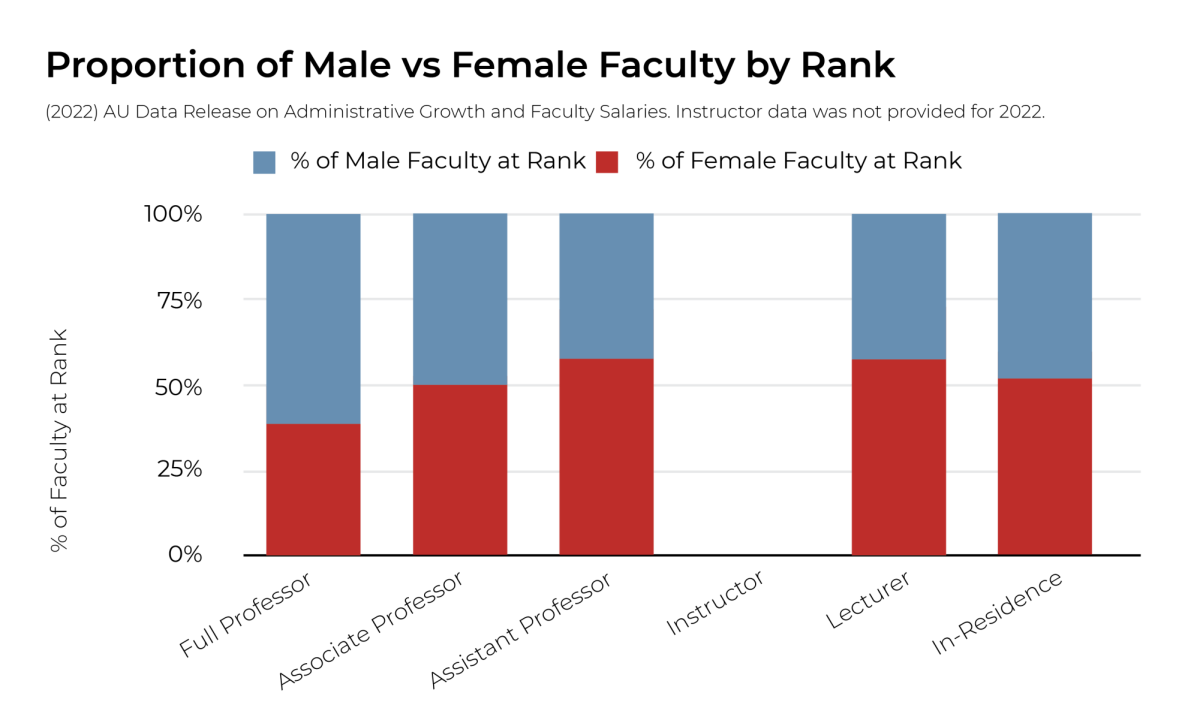

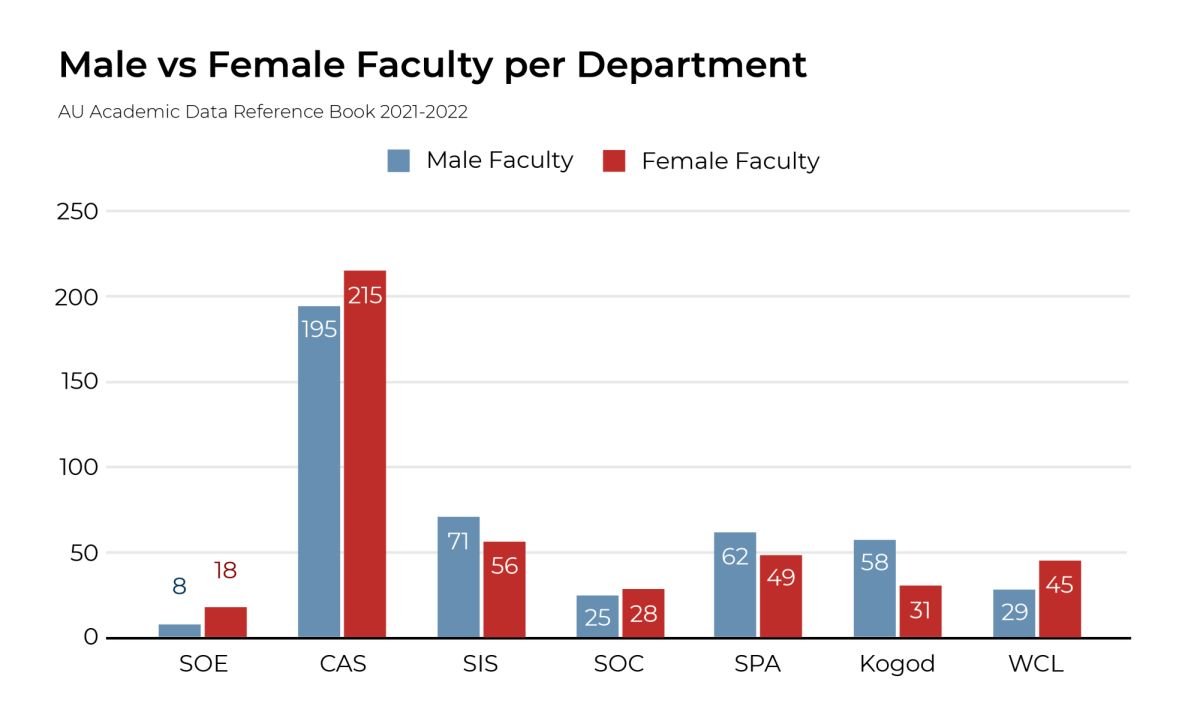

In 2022, 38% of full professors at AU were women, according to the dataset. Comparatively, in 2022, 51% of all faculty at AU were women. Men are disproportionately represented at the highest paid faculty rank, which contributes to the overall gap in average faculty salaries at AU.

Disparity in rank exists nationwide. In fall 2022, only 35% of full professors in the U.S. were women, said Colby, the AAUP researcher. A wage gap still exists within the full professor rank at AU as, in 2022, the salary for male full professors was $10,261 more, on average, than female full professors, according to the Office of the Provost’s dataset.

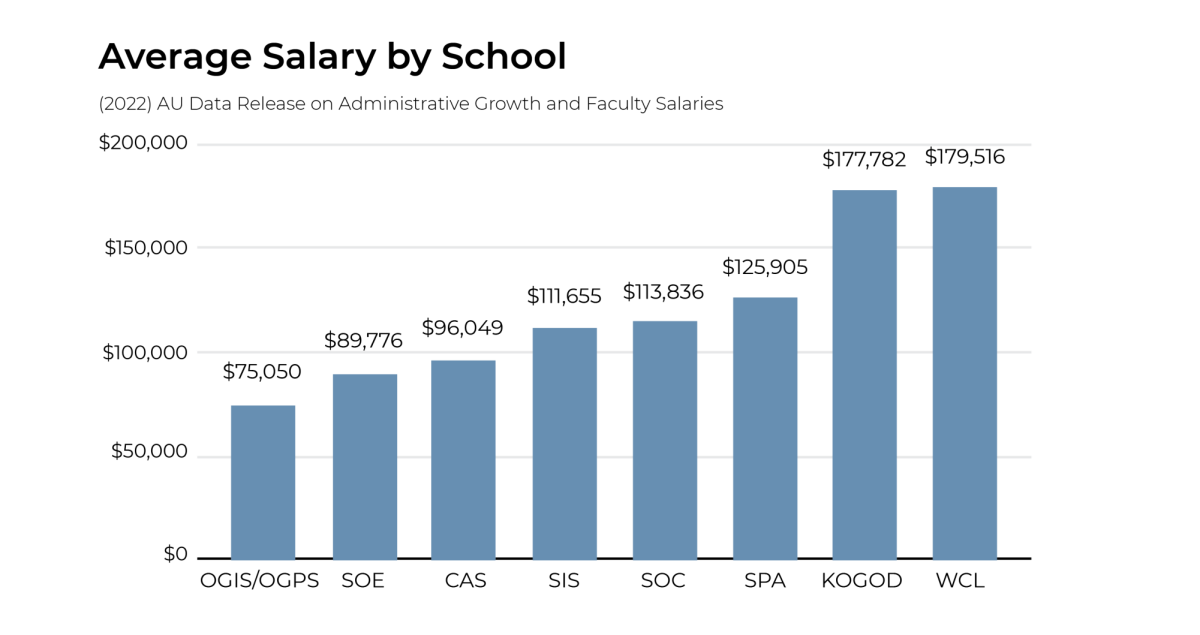

Pay disparities between disciplines also affect the wage gap. Kogod School of Business and the Washington College of Law, both of which boast higher average salaries than other colleges at AU, have unequal faculty distribution by gender, according to the dataset.

However, they pull the gap in different directions. WCL shrinks the gap with its high pay and high proportion of female faculty. Kogod widens the gap, with nearly two male faculty for every female faculty member.

The data doesn’t tell the full story. On the national level, when accounting for rank and discipline, a gap still exists, according to Colby. This means among faculty of the same rank in the same school, there are still differences in pay. AU does not provide individual salary information which makes this hard to confirm at AU.

Some information is never collected, according to Dana Britton, a sociologist who chairs the labor studies and employment relations department at Rutgers University.

“There’s all kinds of stuff that’s not captured in your data,” Britton said. “People get a summer off, or they get extra pay for doing this or that, or they get student help. A lot of that stuff is just done on the basis of a handshake. And my sense is the inequity is in salary, but it’s also in that.”

In a statement to AWOL, Monica Jackson, deputy provost and dean of faculty academic affairs, said AU is an equal opportunity employer and is firmly committed to establishing and maintaining equity in faculty salaries without regard to sex or any other discriminatory factor.

“Faculty salaries are established based on rank, experience, and position and in accordance with applicable compensation-related provisions within University policy,” Jackson said. “In addition, the University utilizes processes to evaluate and determine whether merit or market-based salary adjustments are necessary to ensure equitable faculty salaries and implement adjustments when appropriate and in alignment with University policy.”

Jackson encouraged faculty members who believe their salary reflects gender pay inequity to contact the university’s Office of Equity and Title IX.

Childcare and negotiations

Meike Meurs, an economics professor at AU who studies the labor market implications of child and elder care, said women tend to leave academia before reaching higher-ranked positions because they often take on more household work after having children.

Meurs said professors tend to be up for promotions near the time they’re having kids. Balancing the time commitment to earn promotions with household work causes female faculty to struggle while climbing the professorial ranks, she said.

“When kids are little, women still do two or three times as much childcare as men do,” Meurs said. “It’s much harder for women to balance, especially young faculty. Before you get tenure, you’re expected to work insanely hard. You know, you have to publish, publish, publish, publish, publish, plus be on committees, plus get good teaching evaluations.”

The closing of the childcare center may exacerbate the issue, Meurs said. “On-campus child care did make a big difference, because it meant women didn’t have to leave 30 minutes early to go get their kid and they got that extra 30 minutes to work,” Meurs said.

Men are also more likely to seek positions at other institutions, prompting raises by their current employer, Britton said.

“In the academy, a way that you get a salary increase is by getting another offer. Generally, it’s the most common way,” Britton said. “And women are less likely to engage in that process and they’re less likely to get a retention offer when they do.”

Women are also less likely to seek professional review as associate professors and to negotiate their salary aggressively, Meurs said.

“Women are under more social pressure to be polite, right, and not be greedy, right?” Meurs said. “And then men are like, ‘I have to establish myself,’ right? The social norms are very different.”

Completely closing the gap is difficult, she said. However, there are ways AU can shrink the gap at a universal level.

Meurs emphasized the importance of understanding systemic biases that affect female faculty when addressing the wage gap.

“You can try to make your faculty aware of the kinds of discrimination women face in publishing and research grants,” Meurs said.

Britton and Meurs both said transparency around salaries and benefits allows men and women to negotiate on an even playing field.

“We had a faculty member in the econ department who was provost, and she negotiated for herself while she was provost, a really excellent salary and also some perks when she was no longer provost for the rest of her career,” Meurs said. “I said to her, ‘Someday, you have to tell me how you managed this, right?’ And she said to me, ‘You know, when I was in the provost office, I saw what the men asked for, and so I just started behaving like one of the men.’”

This article was originally published in Issue 35 of AWOL’s magazine on November 19, 2024. You can see the rest of the issue here.