Editor’s Note: The AP Style Israel-Hamas Topical Guide is “calling the present conflict between Israel and the militant Palestinian group Hamas a war, given the widespread and ongoing nature of military operations in Israel and Gaza.” The guide also recognizes the antecedent context of a 75-year Israeli-Arab and Israeli-Palestinian conflict. AWOL is following that guidance in our reporting. Any feedback on this article can be emailed to [email protected].

When Aisha White, a Ward 5 resident, saw an Instagram post from musician Yaya Bey encouraging food donations to local pro-Palestinian encampments, she got ready to cook coconut curry for people at the George Washington University encampment.

White, an art and social justice fellow at the Maryland arts center VisArts, used a meal donation website to sign up for a donation time slot and asked people on Instagram to help her.

Bey sent White $300 to buy groceries, White said. Others volunteered to help her cook and travel to the encampment.

When she arrived at GW’s University Yard, White said she saw protestors engaging with the encampment and sharing each other’s company. People made signs, brought decorations and crafted bracelets to match the red, white and green of the nearby Palestinian flag, White said.

The encampment was well-organized and recognized the seriousness of the latest Israel-Hamas war, according to White. It also provided a calm space for people to share their voices and engage in deep conversations, she said.

“Yes, there’s a lot of anger, but when you give space to process anger, there’s always joy underneath in some form,” White said. “And they left a lot of space for celebration of solidarity.”

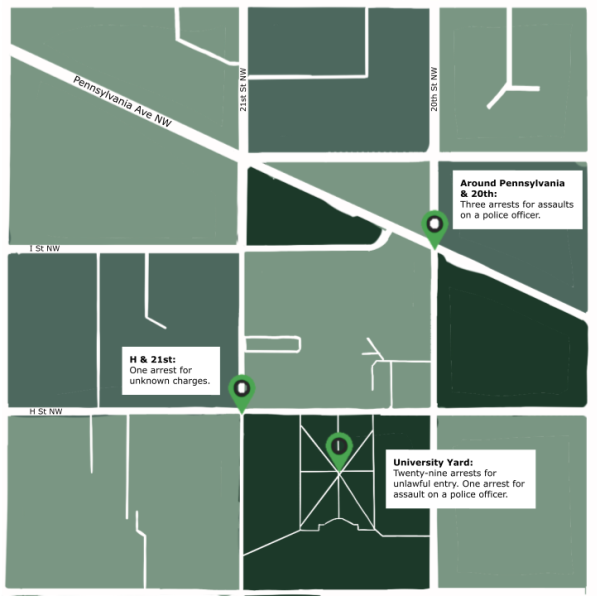

But that space is no longer there. The Metropolitan Police Department cleared the encampment on May 8 and arrested at least 33 participants because of an increase in volatility, Police Department Chief Pamela Smith said at a May 8 press briefing. GW President Ellen Granberg said in a May 8 statement the encampment, which lasted 14 days, was unauthorized and not safe.

For some protestors, that encampment was more than just tents and chanting. The conversations, activities and variety of people inside the encampment created kinship and fond memories that some participants said the Police Department couldn’t arrest or disperse away. Meanwhile, some students countered the encampment with their own demonstrations and some organizations said the encampment was hateful.

People who entered the encampment to counter-protest were assaulted, said Executive Assistant Chief of Police Jeffery Caroll at the press briefing, not noting who the assaulters were.

Over the summer, GW Vice President and General Counsel Charles Barber also asked a federal court to issue orders for five students to stay away from campus for six months, according to a July 26 Instagram post by the DMV Students for Justice in Palestine Coalition, an umbrella organization of students who organized the encampment.

But when school returned, pro-Palestinian protestors returned as well. On Aug. 22, the first day of classes, some chanted in front of a gated University Yard, according to an Aug. 22 Instagram video by the DMV SJP.

One person beat a rhythm on the gate as police stood in front of the space previously filled with tents and people.

A Community of Conversation

Students from Gallaudet University; Georgetown University; George Mason University; Howard University; the University of Maryland; the University of Maryland, Baltimore County; GW and AU organized the encampment, according to a DMV SJP Instagram post.

Student organizations from three of those universities also organized a pro-Israeli rally on May 2, the seventh day of the pro-Palestinian encampment, according to a May 1 Instagram post by UMD’s Mishelanu chapter.

The chapter organized the rally with the GW Jewish Student Association, GW for Israel and Students Supporting Israel at AU. None of the organizations responded to multiple requests for an interview or comment.

The coalition of students who organized the pro-Palestinian encampment also did not respond to multiple requests for an interview or comment.

Kaedence Jairl, a line cook who lives in the NoMa neighborhood of Washington, attended the pro-Palestinian encampment and said he felt a sense of comfort when he saw students from across the region advocate for Palestine.

“Today more than ever, there’s not a lot of causes that are bringing people together and it sucks that it’s taking this to get people to want to, I guess, be a part of something other than themselves,” he said.

Students at the encampment demanded that the eight universities disclose investments and endorsements, divest from Israel, end academic partnerships with Israel, drop charges against pro-Palestinian organizers and protect pro-Palestine speech on campus, according to an April 27 Instagram post. The post also listed university-specific demands for some universities.

Four months after the encampment ended, GW students discussed those demands and future meeting plans with GW Provost Jeffery Brand and Senior Vice Provost for Academic Affairs Teresa Murphy on Sept. 6, according to two videos of the negotiations posted by GW’s SJP chapter.

Murphy said she will tell Granberg and GW Chief Financial Officer Bruno Fernandes about the demands, including publishing the university’s investment information and allowing students to influence the university’s investments. But Murphy said she doesn’t think the university is divesting from organizations.

“I could be wrong, but I just want to be as transparent as possible,” Murphy said in the recorded meeting.

GW is not considering changes to its investments, academic partnerships or process for handling community standards, according to a May 10 statement by the university. That statement came the same day leaders of seven student organizations discussed demands with administrators, according to a May 10 DMV SJP Coalition Instagram post.

Those seven organizations, which the Coalition listed in the May 10 Instagram post, were placed on suspension or disciplinary probation, according to an Aug. 19 Instagram post by GW’s SJP chapter.

GW does not currently list any of the organizations as having conduct violations, according to the Division for Student Affairs’ database.

As community members organized the encampment that led to those May and September meetings, Jairl watched. He watched people form one common vision using a variety of backgrounds and forms of advocacy, he said.

“It’s incredible to see so many people of diverse cultures and religions want to come together for a single cause [and] taking time out of their days and weeks and being part of this as much as they can,” Jairl said.

The Anti-Defamation League and the Louis D. Brandeis Center, both nonprofit organizations that advocate for Jewish communities, have stated that some SJP chapters promote violence and celebrate terrorism.

In an Oct. 26 letter to universities referring to SJP chapters broadly and not specifically Washington-based chapters, League Director Jonathan Greenblatt, Center President Alyza Lewin and Center Founder Kenneth Marcus said SJP chapters may harass and discriminate Jewish students if university administrators don’t check them.

“SJP is a network of student groups across the U.S., which disseminate anti-Israel propaganda often laced with inflammatory and combative rhetoric,” the three leaders wrote in the letter.

For Jairl, though, SJP leaders organizing an encampment in Washington created a sense of community he hadn’t seen other pro-Palestinian movements create.

A supporter of the pro-Palestinian movement since 2021, Jairl said he’s watched documentaries, read books and browsed YouTube videos about Palestine. People in his Iowa hometown didn’t share his mindset towards advocacy, though. Washington, he said, was different. When Jairl got to the encampment, he saw activism take the form of philosophy tables, teach-ins and film-watching.

“I think a lot of people really thought that they could really be a part of this and make change in the world if they got together and did something like this,” he said. “When Columbia went up, so many others went up right after that. I thought that was just really incredible.”

People across the country organized about 1,150 encampments between April 17 and May 12 related to the latest Israel-Hamas war, according to an analysis of Armed Conflict Location and Event Data’s dataset by the Bridging Divides Initiative, a research organization based at Princeton University.

Protestors organizing those encampments in 26 days could have shown their perspectives were popular, said Vadim Ustyuzhanin, a visiting lecturer and junior research fellow at the National Research University in Russia who published research on why students protest.

“If you see 10 people on the street, it’s not very emotional for you, but if you see 10,000, for example, a president, [or] you, for example, can be scared by that,” Ustyuzhanin said.

Continually protesting in encampments also creates stronger pressure than other forms of protests, according to Andrey Korotayev, a visiting lecturer at the research university, who published joint research with Ustyuzhanin.

“If you go out, make a sort of demonstration, and then disperse, it does not produce the same result [as] if you came come out to a certain place, make a demonstration, do not disperse and continue to occupy the place for one day, two days, a week, two weeks,” Korotayev said.

Throughout the two weeks people protested at GW encampment, Ward 5 resident Shai Huq saw a common thread: everyone was always open to talk. Huq, who works in communications, said people struck up new discussions while waiting for food and welcomed others to join pre-existing conversations.

“What I consistently found was; I would have maybe one or two people that I knew and we were talking and people walking by would get a hit of our conversation and decide to join in,” Huq said.

People would talk about emotions, passions and their favorite art forms, Huq said, and that made talking a form of learning.

To GW for Israel, a GW student organization, some of those discussions were hateful. In an April 25 Instagram post, the organization released a statement alleging that some pro-Palestian protestors’ chants, like “There is only one solution, intifada revolution,” endorse terrorism.

Before Huq was a part of those chants, she saw them on Instagram. Seeing photos and videos of the encampment gave Huq a wake-up call, she said.

“I was sitting on my couch just thinking, ‘What am I doing?’ And the answer was nothing,” Huq said. “Quite literally, in my opinion, at that time, the least that I could do was come and witness, right?”

When she got to the encampment, Huq felt like she was part of a community, she said.

“It was amazing,” she said. “I got to have so many conversations and make so many connections with people that I wouldn’t have had access to that now I have longer term relationships with.”

Community was front of mind for Huq while she attended the encampment. For her, the encampment was a way to imagine and talk about what the pro-Palestinian movement could look like.

“I don’t think the point of the protests was to know what to do,” Huq said. “It was to acknowledge that something is wrong, and that something must be done. And I think that is the power of a space like that; because then, it leaves room for curiosity, for growth, for adaptation.”

A Community Remembered

On May 8, police cleared the encampment and arrested 30 people inside the encampment and three people related to the encampment at 20th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, Police Department Chief Pamela Smith said at a May 8 press briefing.

Police arrested another person on May 10 at a separate pro-Palestinain gathering that started May 9, according to a May 10 DMV SJP Instagram post.

GW administrators suspended 8 students in relation to the advocacy initiative, according to a May 4 Coalition press release. It’s unclear when administrators issued those suspensions.

Earlier, the Coalition made an April 26 Instagram post saying GW administrators temporarily suspended six students. It’s unclear when administrators issued those six suspensions and whether they are part of the eight suspensions referenced in the press release.

As with all schools, GW cannot disclose personally-identifiable information about students, including suspensions, without students’ or parents’ permission, according to Subpart D of the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act.

GW Media Relations Assistant Director Julia Metjian referred AWOL to published statements and messages from Granberg and did not provide additional comment or interview.

Graham Piro, a campus rights program officer at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression advocacy organization, said universities should respond proportionally to encampments and protests while still enforcing their policies.

“The university does have the authority sometimes to intervene in these encampments,” Piro said. “It’s just a question of the means they use to clear out the encampments and also ensuring that the force that they use is proportional.”

Three GW policies explain what is and is not allowed during on-campus demonstrations. First, GW’s Demonstrations policy allows students to gather on GW’s campus as long as they don’t endanger people, disrupt university activities and block university spaces. It also allows GW to determine when and where people organize and what objects they use.

Second, the Disruption of University Functions policy lists “engaging in demonstrations that exceed the bounds of free assembly or lawful advocacy” as prohibited disruptive conduct, in addition to reiterating much of the Demonstrations policy.

Finally, GW’s Code of Student Conduct prohibits demonstrations from occupying university facilities and spaces regardless of if they’re otherwise in use.

In the four messages GW President Ellen Granberg published during the encampment’s 14 days, she said the encampment broke several university policies.

Granberg did not specify which policies the encampment broke, but linked to GW’s Free Expression page twice, which says speech may be regulated when it is obscene, threatening, violent or involves illegal conduct.

In her May 5 message, Granberg said the police department was talking with and supporting GW’s administrators.

When police cleared the encampment three days later, the GW for Israel student organization commended the police department in an Instagram post, saying they protected students.

Huq was out of town the night the police cleared the encampment, but she watched the events unfold through an Instagram livestream. She said it hurt to watch.

“I kept calling it guilt that I wasn’t there, but I actually think it was grief,” she said, “because we got to watch them get pepper sprayed, crying, being the most honest versions of humans that are doing something that they think is right; and then getting punished for it and knowing the consequences but still not being ready for them when they actually happen.”

Police cleared the encampment because some participants assaulted a police officer, probed GW buildings and were potentially gathering weapons in the encampment, according to Carroll, the executive chief of police who spoke at the May 8 press briefing.

“Some of these indicators continue to raise a concern for the Metropolitan Police Department,” Carroll said during the press briefing. “And that’s what caused us to change our posture to ensure we can maintain the safety not only for the demonstrators that are there in the encampment, the students at the university, but also the community as well.”

When Huq was at the encampment, she saw designated safety officers protect community members and keep the location clean, she said. Huq also said she didn’t see weapons at the encampment.

“And the only time that the rage ended up bubbling over was when outside agitators came in,” Huq said.

The Police Department did not make a representative available for an interview or provide a comment.

Ninety minutes before police cleared the encampment, Jairl left. He had work in the morning and people weren’t expecting anything to happen that night, he said. He didn’t know there wouldn’t be an encampment to return to after his shift ended.

Without the encampment, Jairl said he couldn’t see the people he had met as often.

“I miss those people,” he said. “Even though I still see them at the protests, it’s something I wish was still going.”

Mixed in with the sad memories of losing connection, though, were Jairl’s positive memories of experiencing the encampment.

“You remember a lot of the art and the people that were there,” he said. “And even though it was two weeks, it felt incredible to be a part of.”

Jairl also knew the encampment wouldn’t last forever, he said, as people would eventually go home. But police officers ending the encampment, he said, was sad and inappropriate.

Road of Activism Ahead

When White was delivering her coconut curry to the encampment on its first day, she felt anxious. People told her the encampment was violent, but she wanted to go anyway, she said, because it was a hands-on way to engage with the latest Israel-Hamas war.

“Finding a way to be there with other folks and actually contribute to the movement even in this tiny, tiny way was really satisfying,” White said. “And it felt nice to have a tangible space to support in our city and our neighborhood, to be able to engage with this issue.”

When she got to the encampment, her anxiety went away because of the variety of people there.

“Feeling and seeing so many different people engaged with the encampment kind of felt like a sense of validation,” she said.

Before the encampment, White primarily engaged in advocacy by planning events and taking care of logistical work, she said. But when GW Encampment protesters showed White appreciation for her food and presence, stepping out from behind the scenes became more appealing.

“I feel like that was just sort of the on-point of opening up like, ‘Okay, you can be involved,’ which is really great and helpful,’” she said.

All the while, she found people to talk about the latest Israel-Hamas war with: the same people she made a coconut curry for.

“I feel less detached from the issue,” she said. “You know how things can feel large and lofty? I feel a bit more connected to it. I know I’m not on the grassroots grounds in Palestine, but I can always do what I can. I feel good about that.”