Troy Davis: A Lesson in Justice

Davis has been on Georgia’s death row for two decades — he’s been convicted for a murder he claims he did not commit. Supporters who argue he deserves a new trial include Amnesty International, the NAACP, Jimmy Carter, Pope Benedict XVI and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, among many others. Stack is one of two AU faculty members who have taken a special interest in his story.

The Troy Davis case has long been contentious. There’s no physical evidence connecting him to the 1989 killing of off-duty police officer Mark McPhail; seven of the nine eyewitnesses who originally identified him in court have now recanted their statements, many claiming that their original statements came under police coercion. Nine people involved in the case signed a letter suggesting another suspect as the actual murderer. Davis has been granted a rare second habeas corpus hearing by the US Supreme Court. Still, the highly-anticipated evidentiary hearing of June 2010 was yet another defeat for Davis, sending him back to death row.

Professor Stack first caught word of Davis’ ordeal during the summer of 2007 when he received a call from the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty (NCADP). Martina Correia, Davis’ sister and dedicated advocate, had come across Stack’s research on death row exonerations and wanted him to speak at an event to raise awareness for her brother. Stack quickly became involved. He has since acted as a consultant for Correia, using his legal background and communication expertise to help raise awareness for Davis’ case.

Another School of Communication professor soon joined the fray. Professor Gemma Puglisi became interested in Davis after reading a news article the night before one of his scheduled executions three years ago, around the same time Stack was growing acquainted with the case.

“Literally, I couldn’t sleep the whole night, thinking about this poor man,” Puglisi said. “And then the next day I ran to get my paper, and it said he had gotten a stay. And that’s when the wheels started turning.”

Both have leveraged their positions as professors to mobilize support for Davis. “The theme of my teaching philosophy is communication for social change,” Stack said. “So I use this as an example of how students can roll up their sleeves and get involved. I know students have different takes on all sorts of social issues. Maybe they agree with me on abolishing the death penalty, maybe they don’t, but I give them the opportunity [to get involved].”

Puglisi has kept in close contact with Davis and considers him a friend. One semester, she dedicated the curriculum of her graduate Public Relations Writing class to his case. Her students wrote op-eds, letters and press releases that helped draw national attention to Davis.

In a similar effort last fall, Puglisi’s undergraduate Public Relations Portfolio students adopted New Hope House as their semester-long client. Located ten minutes from Georgia Diagnostic Prison, the organization provides families of death row inmates a free place to stay while awaiting the execution of their loved ones. The class created campaigns to rebrand the non-profit’s image and help it receive grants.

***

Davis has gained so much attention not only for his proclaimed innocence. He has gained a reputation as a man who has touched many lives.

Stack noted that Martina Correia seemed to never lose spirit, despite her brother’s many legal defeats. When he once asked her by email how she was able to maintain her positive outlook, Correia replied, “If you ever met my brother, then you’d know the answer.”

Davis has an influence that extends far beyond the bars of his prison cell. One of Puglisi’s graduate students wrote to Davis for advice about contacting his father, who was on California’s death row for gang-related crimes. Other people around the world send letters to Davis, asking for his guidance and thanking him for being an inspiration.

“I’ve mentored a few pen pals by giving them ways to identify when their kids are pulling more toward their friends’ ways of thinking, away from how they were raised,” Davis wrote in a letter to AWOL. “I’ve also given kids examples of my life and how they need to be more independent thinkers while staying away from bad situations. They need to realize it only takes a few seconds to get into trouble and a lifetime to get out. They need to think about their actions before they act, because prison life is like a jungle. Even the strong become prey or victim.”

Having met Davis, Stack has an acute sense of exactly what’s at stake. “I don’t know what he was like 20 years ago,” Stack said. “I have a glimpse of what he’s like now. If he was some sort of ‘bad boy’ as a teenager, he’s certainly been rehabilitated, and if that’s part of what our penitentiary system’s all about, I think he’s a success story.”

Davis’ lawyers are now working on additional appeals. The state of Georgia has not yet set a new execution date.

Davis expressed gratitude for his sister and for supporters like professors Puglisi and Stack. “All of them have united hundreds of thousands to be my voice, which has forced Georgia to look at my case and not rush to execute the innocent,” he wrote. “It has shown the world how unjust the American justice system is for the poor and people of color. Because of my faith in God and all these supporters, I’m still alive today fighting to prove my innocence.”

Stack maintains that the death penalty is rash, regardless of whether Davis is innocent or guilty. “At a minimum, if the state of Georgia still thinks he deserves punishment because they’re not convinced he’s innocent, then he stays in prison and he continues contributing to society behind prison bars,” he said. “But he can’t make a contribution if his life is snuffed out.”

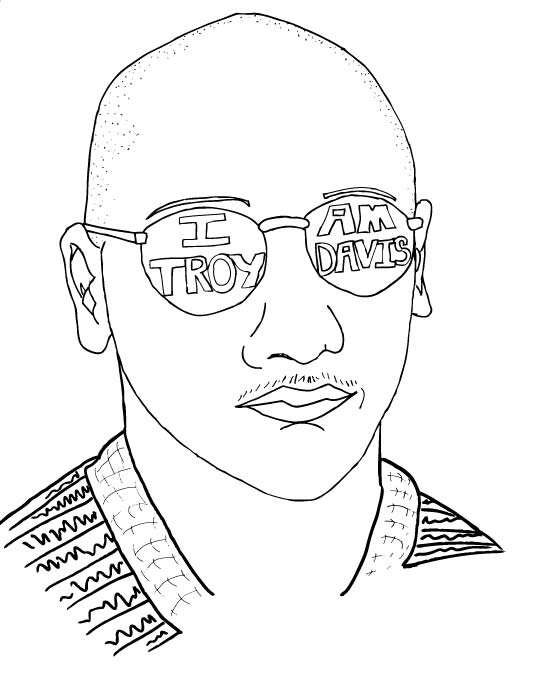

Students can learn more about Troy Davis and how to get involved by visiting the websites of Amnesty USA and the NCADP. The NAACP also has a campaign, “I Am Troy,” with updates, a petition and appeals for action. In the meantime, Davis’ life remains in precarious balance. The efforts of advocates ranging from Amnesty and NCADP to Stack and Puglisi’s students may well determine his fate.

“Our school is known for kids who really care,” Puglisi said. “When we started as a university it was our mission that we help the community. And that’s what changes laws. It’s people who are passionate about changing wrongs to rights, and making the world a better place for everyone.”