A bid to turn Chevy Chase, a neighborhood in Northwest Washington, into a historic district has ignited debate among community members that it would lead to less affordable housing and perpetuate a legacy of exclusion.

Living Chevy Chase, a group of homeowners, opposes the historic district bid. Jim Feldman, a founding member of the group, said many residents have put a focus on inclusion in the neighborhood. The application for a historic district detailed Chevy Chase’s exclusive history.

“That exclusiveness extends to the present day and a historic district would tend to perpetuate it for that reason, because it would make change — in those parts of the area that could be changed and that are open to that — it would make it more difficult and more expensive,” Feldman said.

The group believes a historic district will make home repairs and alterations less affordable and more difficult, limit energy efficiency and perpetuate a legacy of exclusion, according to its website.

The Chevy Chase D.C. Conservancy proposed a historic district that included residential and commercial areas, according to the 2023 application. The designation of a historic district would put guidelines on building design in order to maintain the historic style, according to the D.C. Office of Planning.

The move has sparked debate among community members who question whether a historic district would affect racial and socioeconomic exclusion, housing prices and home alterations.

Mary Rowse, the resident who submitted the application on behalf of the conservancy, spoke at an Advisory Neighborhood Commission meeting on Feb. 12. She said Chevy Chase should be designated as a historic district because developers are buying properties, building large houses that don’t align with the neighborhood design and selling them for more than the original houses were worth.

“Before they even get put on the market, [developers are] getting them in good prices and then simply doing what they want, which is to maximize their return, and then move on to the next project,” Rowse said. “We are left with the destruction in their wake and with the high prices.”

Rowse said that the historic district will make the neighborhood less exclusive by preventing the development of more multi-million-dollar houses.

Feldman said that the high cost of living in Chevy Chase already makes the community unaffordable and that there should be opportunities to develop unused areas in the neighborhood.

“And that would lead to more inclusiveness for the neighborhood,” Feldman said. “And all of that would be more difficult or maybe impossible if it was a historic district.”

Chevy Chase’s exclusionary history

Riordan Frost, a senior research analyst at the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, has studied historic preservation in the district and used to live in Chevy Chase. He said historic districts are generally designated after they have been gentrified.

Historic districts make property values increase faster than surrounding districts, Frost said. They can hinder new development by making it more difficult to build, causing new developments to move outside of that neighborhood.

Feldman said that he opposes the historic district designation because of the eclectic neighborhood styles.

“It doesn’t make sense to impose this kind of uniformity, this uniform provision that everything has to be preserved,” Feldman said. “What’s made the neighborhood great is that people have been able to do what they want and change things and make things do something different.”

Historical districts also raise property values and lower the poverty line by either attracting wealthier residents or pushing out lower-income residents, according to a 2016 article in the Journal of the American Planning Association.

Historic Chevy Chase D.C. is an organization that researches and documents Chevy Chase’s history, according to its website. Carl Lankowski, its president, said affordable housing and the neighborhood’s history of pushing out people of color were the foremost issues in the conversation.

Historic Chevy Chase D.C. switched to a racial justice agenda during his presidency in response to former President Barack Obama’s presidency and racial tensions, Lankowski said.

“We began to ask a question, ‘How did Chevy Chase get to be the way it is?’” Lankowski said. “And we reached the — one of the critical questions is: why is it so white in a city that, in 1971, was 70% Black?”

According to the application, the developers of Chevy Chase required minimum costs to build each house and only marketed to white Washingtonians as a way to keep out people of color. There were three Black covenants in the nearby area, all of which were pushed out in favor of the white, suburban development, according to the application. This included community areas that the Chevy Chase Citizens Association, which stipulated that members had to be white, had advocated for.

In 1940, only four of the 17 squares in the historic district had non-white people, according to the application.

According to the D.C. Office of Planning, a historic district gains official recognition due to its contribution to both cultural and aesthetic heritage in Washington. The Historic Preservation Review Board considers the significance of events, history, important individuals, architecture and urbanism, artistry, work of a master and archaeology.

The residential houses in the proposed historic district will range from those built from 1907 to 1964. More than 30 of the 70 Washington historic districts are made up of local neighborhoods, according to the D.C. Office of Planning.

The affordable housing question

Lankowski, not speaking on behalf of Historic Chevy Chase D.C., said he opposed the historic district because it could make it harder to build affordable housing.

“We need to be part of the solution to citywide problems, not to continue to be part of the problem,” Lankowski said. “And so what we learn from our researches, over the last 10 years, impels us to embrace changes to the neighborhood that are uncomfortable to people that have lived here for a long time.”

New construction in historic districts is rare, and there is significantly less new construction than in non-historic districts, according to a 2022 D.C. Policy Center article. Ward 3 already has six historic districts.

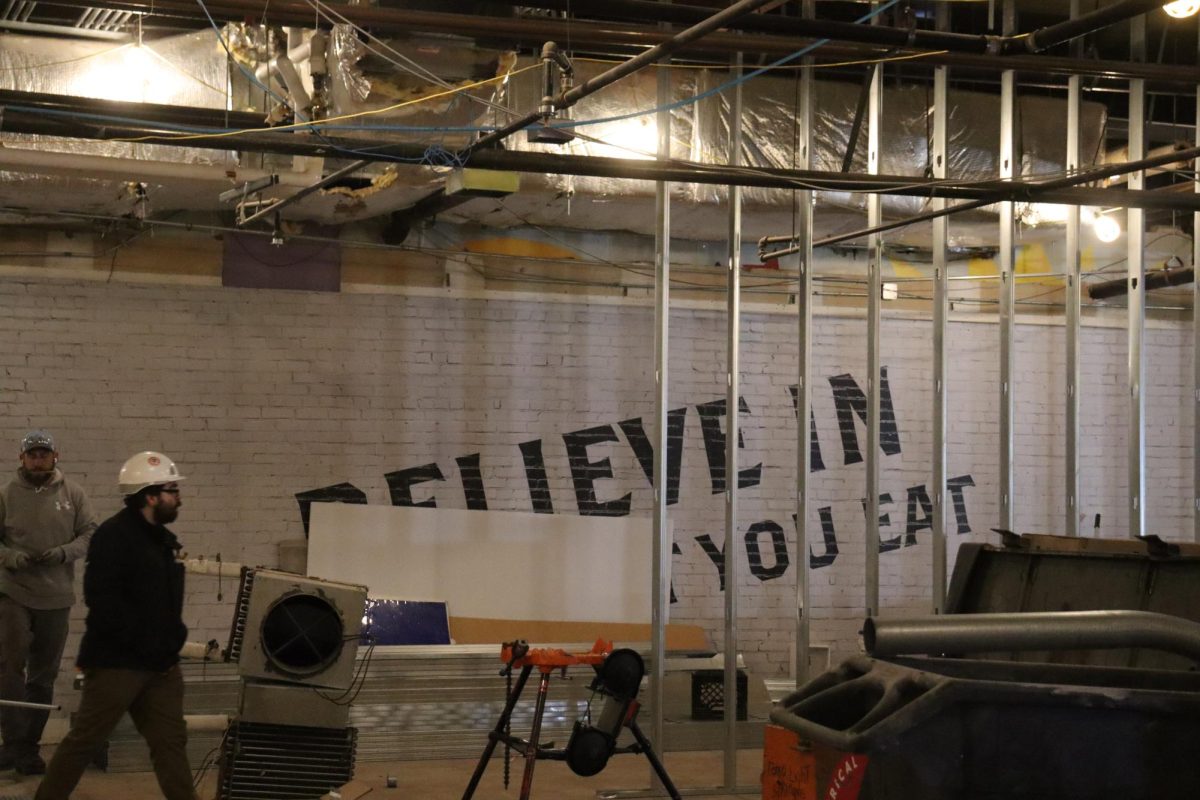

The Chevy Chase Small Area Plan, proposed in 2022, is a plan to build sustainable and equitable growth along Connecticut Avenue in Chevy Chase. Part of it includes a redeveloped civic core — tearing down and rebuilding the Chevy Chase Library and Community Center — and adding a mixed-income housing development.

Contributing buildings are buildings that reflect the designation criteria, said Gretchen Pfaehler, the architectural historian on the Historic Preservation Review Board. Non-contributing buildings are those that were built outside of the designated time period. The civic core would be considered non-contributing.

Pfaehler said there is more flexibility to alter non-contributing buildings and build on non-contributing properties than contributing ones. Pfaehler, speaking hypothetically, said those changes would only come under the HPRB if it had a substantial impact on the character of the neighborhood.

“If you had a multi-story building, and you wanted to build 20 stories next to the one story — that changes the overall character of the historic district, and starts to detract from the other buildings,” Pfaehler said. “So, you can’t impact the historic buildings that are contributing.”

The future of the civic core is still unsure, as Pfaehler could not speak on Chevy Chase specifically. However, she said that the guidelines for each historic district are different.

Rowse said that the historic district would allow more transparency in community projects, specifically the civic core.

“In a historic district, there’s a lot of transparency and information that would be shared,” Rowse said. “So people would not be in the dark and would not have to fight and use all their resources to try to get some kind of compatibility between a commercial construction and residential construction.”

Lankowski said that the Chevy Chase question will send a signal to other neighborhoods in Ward 3 to build more affordable housing in order to mitigate the housing crisis.

“And my own feeling is that every neighborhood, bar none, should have skin in this game — should be contributing to adding to the affordable housing,” Lankowski said. “If every neighborhood did that, it wouldn’t be a crisis anymore.”

Frost said that many neighborhoods don’t build more housing for several reasons, including zoning, that contribute to the affordability crisis.

“What you’re going to see is generally the more privileged, more resourced people being able to live in those neighborhoods,” Frost said. “And typically — in D.C. and in America — because of white privilege, and because of institutional racism and everything, that’s just going to become a whiter, wealthier district.”

Historic districts also cause a decrease in places to rent, Frost said, as places that were being rented may be sold to wealthier people who could afford to buy them. In turn, the neighborhood loses the lower-income families who could afford to rent those units.

Frost said he sees the merits of historic districts, as the designation can prevent historic sites from being torn down; however, he said his perspective is to designate specific buildings where historic events have occurred, rather than entire districts.

“It just seems like such a broad answer to a very specific question in terms of [preventing mass teardowns], and then it really kind of limits who can be in that neighborhood,” Frost said.

Pfaehler said that the Historic Preservation Review Board takes community input into consideration during the review process.

Lessons from the past

When a Chevy Chase historic district was first proposed in 2008, 77% of Chevy Chase residents present voted against becoming a historic district, according to a November 2008 ANC meeting. The ANC voted against creating a Chevy Chase historic district after the survey.

The historic district was first proposed by Historic Chevy Chase D.C. The organization hasn’t released an official stance on the 2023 historic district application as of March 24. Lankowski said that the organization learned that residents were largely opposed to the historic designation.

“In deference to their wishes, we never went through with the application and submitted it,” Lankowski said.

Lankowski said residents’ main concern was the ability to repair and alter their properties. The neighborhood was designed by various builders and architects, creating an eclectic assortment of houses in variations of the Colonial Revival style, he said.

“This is all something that was done organically and in a decentralized fashion,” Lankowski said. “So what people were really objecting to was the imposition of a one size fits all.”

ANC Commissioner James Nash, who said he is undecided on the issue, said that the environment was part of his concern about the historic district, including installing energy-efficient windows and solar panels on rooftops.

“Second problem is replacing windows on the front of your house with more energy efficient windows,” Nash said. “When I lived in an historic district 30 years ago, that was a big problem — couldn’t do it. They say the rules have changed a little bit now.”

Nash said he is waiting to hear more arguments that work toward the common good.

“There is a problem in our neighborhood, with people tearing down a house and replacing it with a house that is too big,” Nash said. “That is so big that it bothers people. It’s out of scale with the neighborhood. And we’ve heard complaints about this.”

Rowse said the historic district would give residents a chance to have a voice in the development of their community.

“Nobody likes to be ignored,” Rowse said. “Nobody wants to have anyone to make decisions behind their back or against his wishes, and in a fair society, a fair process, people get a chance to speak out.”

Pfaehler said historic districts are meant to recognize history and how we can live within it.

“It recognizes the value for future generations of a site, so, really, it becomes an asset for broader public welfare,” Pfaehler said. “And it does so by recognizing the events that happened in the past that were important to people.”