Daniel Kerr is the associate director of American University’s Public History program and the founder of the Humanities Truck program. Kerr specializes in community history, oral history and public history. Kerr’s research has focused on the causes of homelessness and promoting social justice for people experiencing homelessness.

As a kid, self-proclaimed nerd Daniel Kerr was torn between a future as a truck driver or a historian.

“I never thought I’d be able to bring those two things together,” Kerr said.

Today, as the founder of the Humanities Truck and the associate director of American University’s Public History program, he has achieved both of his childhood dreams.

The Humanities Truck is a customized delivery truck that can act as anything from a recording studio to an art gallery, Kerr said. The truck’s purpose is to democratize knowledge through “collecting, exhibiting, preserving and expanding dialogue” in Washington, D.C., according to the Humanities Truck’s website.

According to the website, the project is funded through grants from the Henry Luce Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The truck is equipped with a TV and speakers that allow interviews to be shared back to community audiences. It also provides a meeting place for exhibitions and public forums.

Kerr said he developed the idea for the Humanities Truck during his time as a graduate student at Case Western Reserve University. There, he worked on the Cleveland Homeless Oral History Project, which sought to analyze the causes of homelessness in Cleveland, Ohio.

When interviewing the homeless population, Kerr said he soon realized it would be more impactful for the participants if the analysis of homelessness in Cleveland was based foremost on their own stories.

“Rather than doing a life history interview, I was going to do a thematic interviewing about their understanding of how homelessness came to be such a predominant part of life in Cleveland, especially for them,” Kerr said.

Kerr said that instead of practicing disengaged reporting, where the interviews are only published within academia, he wanted the information to be shared within the community he was engaging with.

“This creates a situation where they can position their own personal experiences in the context of others who are similarly situated, or perhaps differently situated,” Kerr said.

One of the truck’s primary goals is to create long-term sustained relationships between the truck and communities in the district by having continuous conversations about the issues affecting the communities, such as homelessness and racial disparity, Kerr said.

The truck does this by attending events throughout the district neighborhoods, such as Adams Morgan Day and the Columbia Heights Day festival. Residents are invited to share their experiences living in the district, according to the Humanities Truck website.

“It’s kind of what I view as a mashup between old school people’s history and digital humanities, making things accessible, generating real world connections and communication,” Kerr said.

Kerr said the truck is not meant to bring people together during large-scale events, like the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, but instead focuses on generating conversations within and from the communities.

Kerr said that in the district, the complex power structures make realizing what needs to change difficult.

“City Hall?” Kerr said. “Are you going to the place where immediate harm is being done, like the shelter itself? The federal government?”

While he said it is difficult for systemic change to occur, Kerr said he believes that it can happen with time and focus.

“Through the concerted, ongoing activity of building movements and transformations, we can make changes,” Kerr said.

Change requires a space willing to host those conversations, which is what the humanities truck aims to provide for the people of the district, Kerr said.

“Rather than think in the abstract about what we think the community wants, just go into that community and ask people, what are their needs, their wants, their concerns?” Kerr said.

One member of his team, Megan Henry, said she was able to get invaluable hands-on experience in the field of public history through the truck’s graduate student fellowship program.

“I’ve been able to get my hands dirty, so to speak, in the field,” Henry said.

Henry said that through this program, she has also been able to explore the complexities of D.C.

“I think it’s cool how unique different aspects of the city are when they’re, like, blocks away from each other,” Henry said.

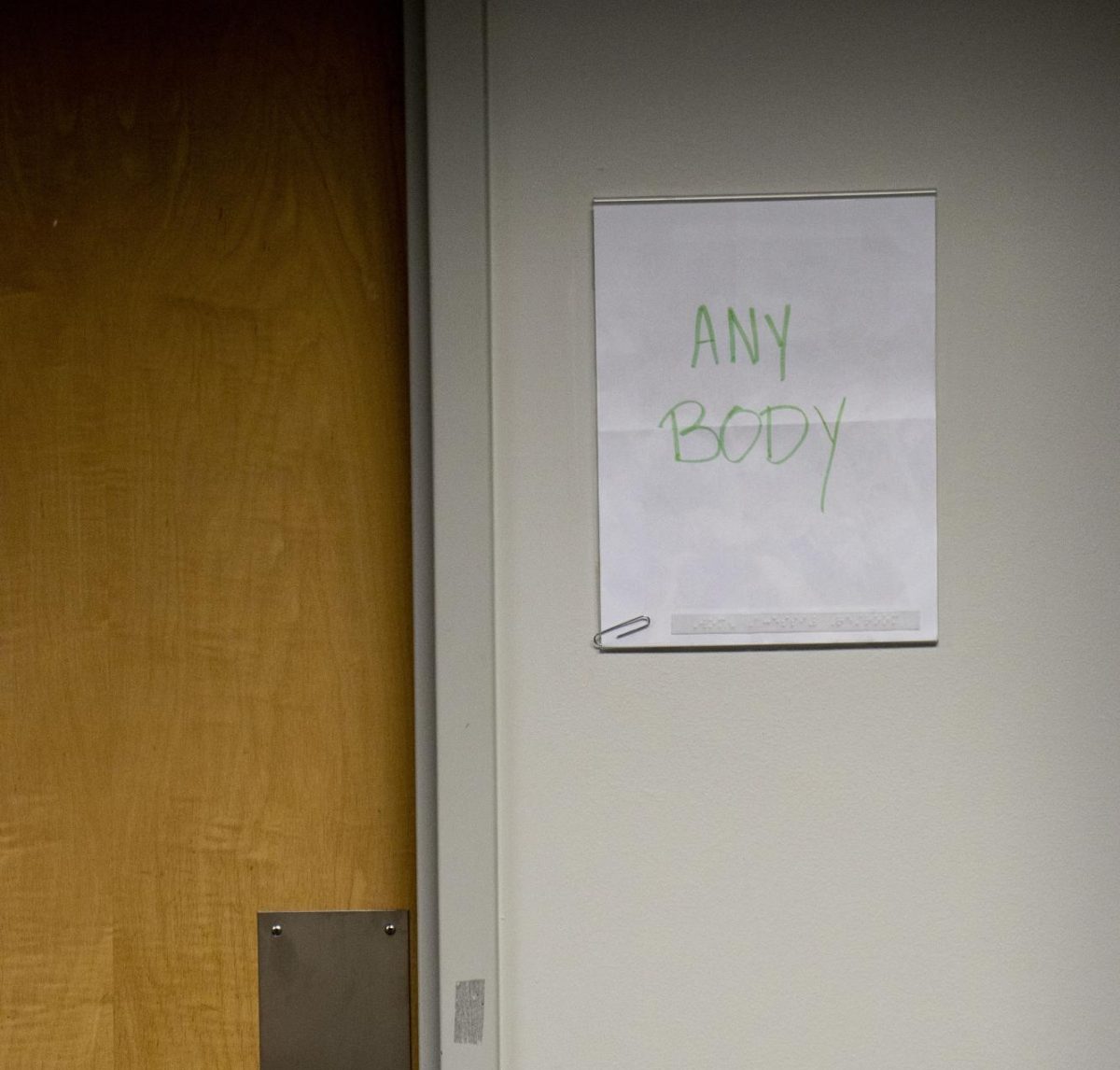

Jane Palmer, another member of the Humanities Truck team, was a fellow during the 2022-2023 term and led the Youth Power Project in collaboration with the Humanities Truck and nonprofit DC Action. With the aid of the truck, this project allows young people to share their experiences of life in the district and changes they want to see made, Palmer said.

“We talked to almost 100 youth who are often not listened to and disregarded,” Palmer said. “Now, we could really amplify their voice through this project.”

Palmer said the project also created a sense of community among the youth interviewees and recalled a button-making activity set up at one of the interview sessions.

“Creation creates connection,” Palmer said.

“You can’t be serious all the time, you have to make time for joy and fun,” Palmer said. “I think that also helps them be more comfortable with telling their stories.”

Palmer said she is proud of the Youth Power Project and that it wouldn’t have been possible without the Humanities Truck.

“I wanted to be listened to as a youth activist by people in power and I want to help facilitate that for young people who maybe don’t feel like they will be listened to or haven’t had the same opportunities,” Palmer said.

Kerr said that Palmer’s project embodies the core mission of the truck, as the experiences of youth add another layer to crucial dialogue centered around issues they face and build connection by welcoming more of the community into these conversations.

Kerr said it is the inclusion of all the different perspectives within the community that makes this dialogue create productive change.

“If we’re thinking about how we want to transform the world, we need to do that with others, with communities, with people in neighborhoods,” Kerr said.