American University confirmed a $30.8 million deficit for the 2024 fiscal year, according to an Oct. 17 budget update. Two questions loom over this year’s deficit: How did it happen? And what are the consequences?

An AWOL investigation of the AU’s finances found that this year’s failure to hit graduate enrollment and undergraduate retention targets, combined with AU’s reliance on student-generated revenue, led to this year’s deficit.

The $30.8 million deficit is around 3.6% of the university’s total $850 million yearly budget and represents a negative gap between earnings and spending for the year.

In response to the deficit, AU has dipped into reserves and cut budgets in multiple departments and offices, Bronté Burleigh-Jones, AU’s chief financial officer, said at an October community forum.

“We are working against a $30 million shortfall due primarily to undergraduate and graduate enrollments coming in lower than our targets,” said Burleigh-Jones and Vicky Wilkins, the acting provost, in a July 19, 2023, email sent to the student body.

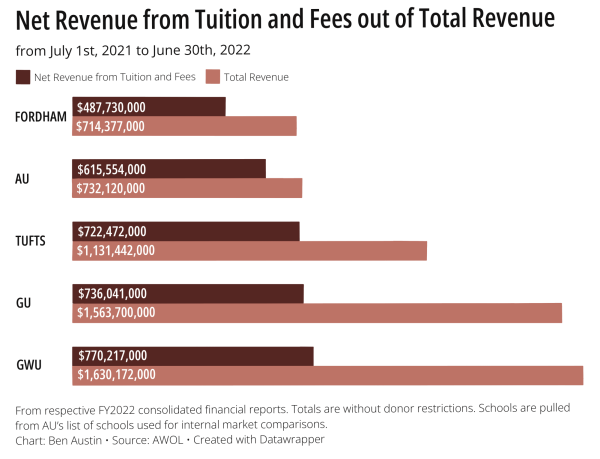

Over 80% of AU’s operating budget comes from student tuition and fees, according to AU’s 2022 Fiscal Year Budget Report. The university’s budget is “significantly influenced by student enrollment and retention,” with 92% of its current operating budget coming from student-generated sources, such as tuition, housing, dining and fees, according to a June 2, 2023, Memorandum.

In comparison, the George Washington University sources about 47% of its operating budget from tuition, according to GW’s 2022 Fiscal Year Budget Report. A large part of GW’s operating budget instead comes from their medical center, as well as individual grants and contracts, according to GW’s Consolidated Financial Statements for the 2022 fiscal year ending on June 30, 2022.

Because a large portion of AU’s budget comes from student-generated sources, the budget is significantly impacted by enrollment and retention rates.

Retention refers to the percentage of students who return each year, according to the Federal Student Aid website. Enrollment is the total number of students who enroll each semester.

AU’s largest non-student-generated revenue stream is WAMU, the Washington D.C. area NPR station licensed by AU, which brought in $31 million in 2022, according to AU’s 2022 Fiscal Year Budget Report.

In comparison, patient care at GW’s hospital brought in $309 million the same year, according to GW’s 2022 Fiscal Year Budget Report.

Another non-student-generated source of revenue for universities is their endowments.

An endowment is a pot of money donated by alumni that is invested and grows over time, said Gergana Jostova, a professor of finance at the GW School of Business. Each year, universities pull a set amount from the pot to assist in meeting their revenue demands.

“Think of it as a special savings account or portfolio that they have typically generated from alumni who donate to the university,” Jostova said. “It’s not just sitting there, it’s not idle cash, it’s usually invested in, let’s say, the stock market or somewhere relatively safe.”

AU’s endowment was $908.9 million in 2022, according to AU’s consolidated financial statements for the 2022 fiscal year ending June 30. Meanwhile, that same year, GW had a $2.41 billion endowment,

according to GW’s consolidated financial statements for the 2022 fiscal year, and Georgetown had a $3.21 billion endowment, according to GU’s consolidated financial statements for the 2022 fiscal year.

Both GW and GU have larger class sizes than AU, according to U.S. News and World Report data. However, Tufts University — a school with a similar class size to AU — has a $2.39 billion endowment, according to its consolidated financial statements for the 2022 fiscal year.

AU pulls around 5% from its endowment each year, Burleigh-Jones said at an October 2023 community forum.

Endowments represent a revenue stream not directly affected by enrollment or retention, Jostova said. A large endowment can help a university weather financial challenges.

“Let’s say Harvard has so much of an endowment that they could probably not get revenue for some time and still survive,” Jostova said. “Most universities don’t have such a big endowment that they can rely on so much to cover their expenses.”

Burleigh-Jones said at an October community forum that AU wants to remedy its reliance on student-based revenue. The Change Can’t Wait donation campaign represents a significant step in building non-student revenue streams. As of October 2023, the campaign had raised $440 million of its $500 million goal, according to AU’s website. AU has also separated its finance and investment departments to improve the management of the budget and endowment.

“We recognize our vulnerability in terms of our tuition dependency in terms of our revenue,” Burleigh-Jones said.

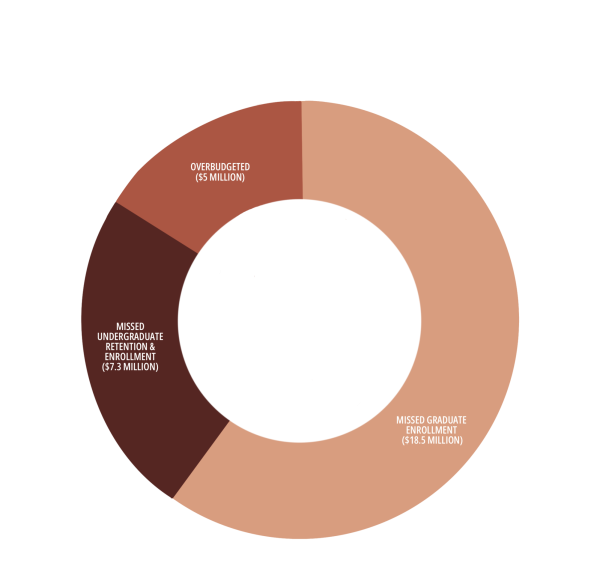

The $30.8 million deficit can be split into three parts: failure to hit graduate enrollment targets, failure to hit undergraduate retention targets and over-budgeted student aid and merit equity funding, Burleigh-Jones said at an October community forum.

“The projected yearly (fall & spring) deficit associated with graduate enrollments is about $18.5m,” wrote Wendy Boland, the Dean of the Graduate Programs at AU, in an Oct. 10 email to AWOL.

AU usually creates two-year budgets, meaning every time a budget is set, it is done in two-year increments, according to past AU budget reports. The yearly budgets are based on predictions of how many students will enroll and subsequently pay tuition, according to a University Budget Development Guidelines memo from 2016.

Burleigh-Jones said that graduate enrollments have historically been challenging to predict. She did not specify why.

“Taking a look at our activity over the last seven to eight years, as it turns out, we’ve hit our target once in that period of time,” Burleigh-Jones said.

This fall, AU’s graduate program missed its residential enrollment target by 11% and its online enrollment target by 27%, Boland wrote in an Oct. 10 email to AWOL.

Boland said that as schools transitioned back to in-person classes, graduate enrollments quickly rose.

“We saw really big spikes in 2021 in grad school enrollments, way above budget,” Boland said.

Since 2021, graduate enrollment rates have fallen nationally, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. The spike and falloff in enrollment rates led to this year’s missed target, Boland said.

“We set the budget way back when we saw the numbers in 2021,” Boland said. “And so then when the market fluctuates, and we have these things that happen, that’s why you see a bigger gap, because of those things.”

Boland said that changes in the international student market also hurt enrollment.

“It’s a lot easier to get into other countries, and some places like Canada are seeing a huge increase in the international graduate student market, where the U.S. is seeing declines overall,” Boland said.

Over 100 graduate students, primarily from Western and Central Africa, couldn’t get visas for the fall semester to study at AU, Boland said. AU expected many of these students to attend. However, many

had visa issues as late as a week before the fall semester.

The School of International Studies saw one of the largest drops in graduate student enrollment, said Mateo Maya, the president of the SIS Graduate Council.

“People don’t want to just go to college because they don’t see the actual return on their investment,” Maya said.

SIS Graduate Program Coordinator Madison Shomaker said that, within SIS, the development management program, which is targeted towards mid-career professionals, saw the largest enrollment drop this year.

However, failure to hit graduate enrollment targets does not make up the entirety of the deficit. For the 2024 fiscal year, failure to hit undergraduate retention and enrollment targets made up $7.3 million of the deficit, according to an Oct. 17 email sent to the student body.

Undergraduate retention has caused problems for AU before. The university also projected a deficit for the 2023 fiscal year, primarily due to missing undergraduate retention targets, Burleigh-Jones said at an October community forum.

“At mid-year, we were projecting a $10 to $15 million shortfall on the year,” Burleigh-Jones said regarding the 2023 deficit. “And I am happy to report that because of our collective efforts, we were able to reduce that shortfall to $4.7 million.”

Housing and dining have also seen issues in recent years, Burleigh-Jones said.

“In the last seven or eight years, we have not hit our housing targets,” Burleigh-Jones said. “That’s a pretty significant thing for us to take a closer look at because that’s an important portion of our revenue flow into the university.”

Burleigh-Jones said that the dining program currently does not generate net revenue for AU.

“Our dining expenses, especially following COVID, as inflation and labor costs have gone up, have outpaced the revenue that we’re generating in dining,” Burleigh-Jones said. “This particular year, we’re actually ahead of what we expected in terms of actual dining revenue, more of our students are signing on to the meal plans. Unfortunately, our expenses are still rather significant.”

The deficit also includes $5 million in financial aid and merit equity spending, Burleigh-Jones said at an October community forum.

“There have been changes in the federal calculation of need for our students and so we needed to add additional funds for financial aid,” Burleigh-Jones said.

Now that the fall semester is underway, AU is looking to combat the deficit. AU is employing a three-part strategy to mitigate the $30.8 million deficit, Burleigh-Jones said at an October community forum.

First, AU is pulling $10.35 million from reserve funds.

Every year, 1% of AU’s operating budget is placed into AU’s reserve funds, Burleigh-Jones said.

“These are funds that are set aside for unforeseen circumstances, either positive or challenges like we’re currently facing,” Burleigh-Jones said. “They are not additional discretionary funds, and they are not to be recurring funding streams.”

Burleigh-Jones said that AU also pulled from reserves to remedy the 2023 deficit.

For the 2024 fiscal year, AU is pulling from its enrollment and compensation reserves, Burleigh-Jones said.

Second, AU is implementing $9.8 million in budget cuts.

This summer, schools, colleges and administrative units at AU were asked to adjust their budgets to make up for the current deficit, according to an Aug. 31 email sent to the student body.

Across the board, most departments and offices faced 2% budget cuts, Burleigh-Jones said at an October community forum. AU allowed different schools, colleges and administrative units to decide on the exact places the cuts would affect internally.

“The savings instructions are not prescriptive; individual divisions/units can make decisions that work for their goals and teams,” wrote Wilkins and Burleigh-Jones in a July 19 email sent to the student body.

Club funding is among the areas that have seen cuts. Typically, the American University Student Government receives about $100,000 each year from the Center for Student Involvement, Ava Falkenrath, the AUSG Finance Chair, said.

“This year we got $80,000 with $20,000 coming from reserves,” Falkenrath said. “We were told that it’s the deficit and that reserves are too large.”

Falkenrath said that the cuts could also exacerbate retention issues with undergraduate students.

“It’s fairly difficult right now because they’re losing money, but they also need to spend money to keep more students,” Falkenrath said. “So they’re like, ‘How can we spend less and spend more at the same time?’”

AU also hopes to regain $9.85 million in institutional expense savings.

“We looked at additional vacancy savings throughout the course of the year, there are always savings as we’re transitioning to fill positions,” Burleigh-Jones said during the forum.

Burleigh-Jones said AU has also delayed certain spending, such as vehicle purchases and maintenance projects, which have been suspended for one year.

AU is taking a hard look at its budget and closely tracking it moving forward, Burleigh-Jones said.

AU plans on creating a one-year budget for the 2025 fiscal year, last done for the 2022 fiscal year, Wilkins said.

“We’re usually on a two-year budget cycle, but this is an important year for us to use as reflection and planning and understanding and analysis of where we are as a university so that we can be ready to allow the new president to come in and fall into a two-year budget cycle,” Wilkins said.

Burleigh-Jones said the fiscal year 2025 budget will likely be less than the 2024 budget.

AU is also looking to the future, where greater demographic shifts could impact the college landscape. According to an estimate shown at an October community forum, from 2025 to 2035, there will be a 10% to 20% decrease in 18-year-olds across the eastern seaboard, one of the university’s target areas for prospective students.

“Very clearly we’re going to be challenged there,” said Burleigh-Jones.

AU is now focused on hitting upcoming enrollment targets. If AU enrolls enough students this spring, it does not anticipate the need for any additional budget actions, Burleigh-Jones said.

“It is absolutely imperative for us that we hit our spring enrollment targets,” Burleigh-Jones said.