Myth Busting: False Rape Reports

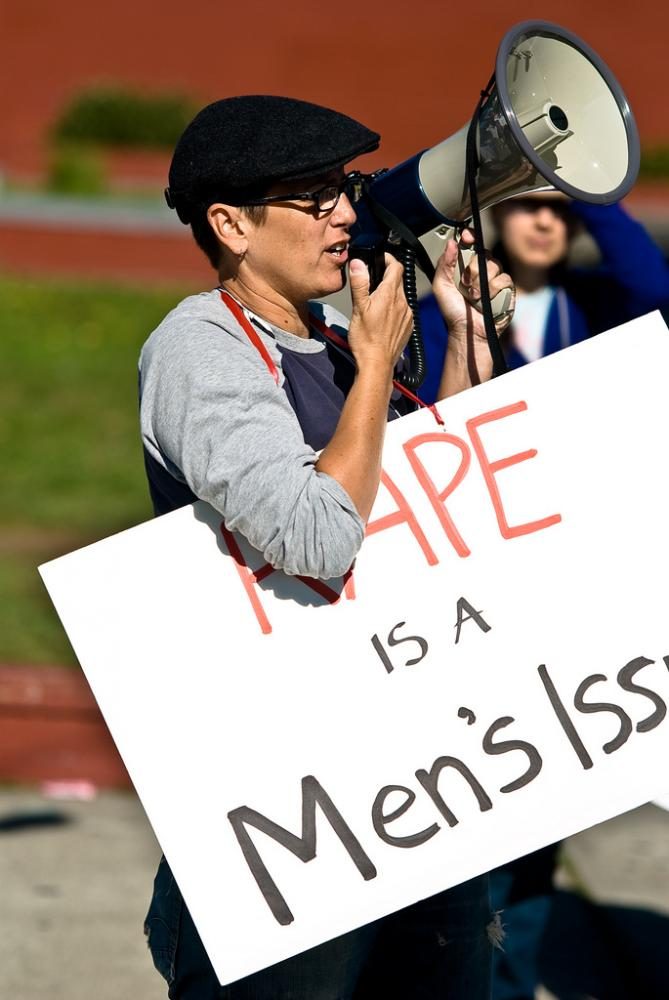

Last week, Alex Knepper’s column generated a buzz on campus and around the country. While many read the piece as an irresponsible condonation of sexual assault, others argued that it was merely identifying an age-old truth: some women routinely get drunk, have sex, and then “cry rape” the next morning because they regret their actions. When CBS interviewed Knepper, he claimed that “thousands” of men suffer from false rape reports. Unfortunately, just as The Eagle was negligent in ensuring that Knepper was writing a responsible piece, CBS also failed to set the record straight with fact-checking legwork. Thus, both media outlets irresponsibly provided Knepper with an opportunity to perpetuate long-standing — and untrue — myths about high percentages of false rape reports. And based on hundreds of online comments, it’s evident that many students fervently believe these myths.

The hysteria surrounding false rape reporting is due to a number of issues, many of which cannot be fully elaborated upon here. They include institutional patriarchy and the lower position of women in the workplace, individuals’ desires to make themselves feel safe at the expense of blaming victims for crimes, and a disregard for a woman’s right to consume alcohol, have fun, and engage in sexual activities without being assaulted.

But most saliently, misunderstandings occur due to errors in police coding procedures, public misconceptions about the motivations for false allegations, and the simultaneous overrepresentation of false reports and underrepresentation of factual cases in mainstream media. It’s also important to recognize that victim-blaming strategies and a belief in high rates of false rape reports are closely related; they feed off of one another to create a cultural environment in which the majority of assaulted women feel too afraid of public rejection to report the crimes committed against them, and the majority of rapists remain free to continue preying on vulnerable victims.

According to a recent study by the American Prosecutors Research Institute, false rape allegations account for two to eight percent of all reported rapes. This low figure may shock many readers who have heard claims that over 40 percent of rape reports are false. In the past, errors in police coding procedures have often been a reason for high claims of false reports; many reports categorized as “false” actually should be recorded as “unsubstantiated” (which means that there is insufficient evidence to move forward with the case) or “baseless” (indicating that the claim is considered truthful, but the incident doesn’t meet specific elements of the crime). Some reasons for incorrectly categorizing reports include pressure on police officers to close out cases and make their departments appear successful, difficulties with agencies not tracking and differentiating between “false” and “baseless” reports, and a lack of supervision within and across law enforcement agencies regarding careful training and implementation of accurate coding procedures.

A primary myth about false rape reports focuses on the belief that women “cry rape” because they are seeking revenge on men who have wronged them in some way. However, according to this study, the reality is that the vast majority of false allegations “are actually filed by people with serious psychological and emotional problems.” And notably, people who falsely file claims usually do not name specific individuals, but instead “involve only a vaguely described stranger.” These research findings support the theory that people who falsely allege rape do so not out of desire for revenge against a specific person, but because they seek general attention and sympathy.

Finally, myths about high rates of false reports are perpetuated by media stories that provide excessive coverage of highly sensationalized cases. News agencies make little effort to reach out to the academic community to include professional opinions about the validity of the majority of rape reports. Instead, the general public is bombarded with stories about “gold-digging” women who falsely accuse athletes or prominent public figures. Very rarely do we hear the countless true stories of women and children who are abused and manipulated by men they know and trust.

I hope you’ll take a few minutes to reflect upon some of the reasons why, so often, people are willing to quickly jump to the defense of accused perpetrators, and are so eager to immediately dismiss the claims of victims. I challenge you, now that you are armed with the knowledge that 92-98 percent of rape allegations are true, to contemplate the reasons why you may be so willing to believe that your neighbor, co-worker, friend, or family member is not a rapist, but that your neighbor, coworker, friend, or family member is lying about being raped. Why do so many of us prefer to dismiss rape victims and defend rapists? Take a few moments to talk with a loved one. Force yourself to face these difficult questions. Only by challenging our preconceptions and educating ourselves about the issues can we achieve justice for rape victims.

Mahri Irvine is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Anthropology.