Aramark at AU: The Search for Solidarity

“They need to pay us more money because now, life is too expensive,” said one Aramark employee at AU. “We need to pay for houses. I have children. I need to pay for babysitting. I have to pay for many things,” she said.

To protect the identities of employees who spoke out about their job conditions, all names have been withheld in this article.

Aramark, an employer of more than 260,000 and an industry leader in custodial services, acquired the contract to provide housekeeping and custodial services at AU in 2001 after purchasing another subcontracting company, according to Aramark spokesperson Karen Cutler. In 2008, the company enjoyed $12.4 billion in profits, operating in 22 countries for thousands of institutions, including over 500 college campuses.

While Aramark’s business has prospered, Aramark-operated facilities have been ground-zero for protests in Texas, Illinois, California, New York, Pennsylvania, and the District for what unions and employees contend are substandard labor policies. Now, employees at AU want their piece of the $12.4 billion.

I. The Benefits

“I can get health insurance, but it is not very good,” said another worker. “It’s not worth it.”

According to the first employee, who has worked at AU for over a decade, no retirement program exists. “[Employees] go home and they don’t bring with them anything. No retirement. Only social security,” she said.

The contract between Aramark and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU– the union that represents AU’s workers) expired on September 30, launching an arduous process of renegotiation that could last up to three years. In the interim period, employees will retain existing benefits including twelve sick days every year and some vacation time, according to an Aramark representative on campus.

“After thirteen years, they get twenty days of vacation. They have short-term disability coverage of up to 26 weeks, which Aramark pays 60 percent. They have maternity leave of up to 2 months,” said the representative.

Employees said that life insurance is also included, but that a more generous contract is needed to ensure a comfortable future for themselves and their families.

“It’s bad when you’re on the job here for twenty-, thirty-, fourty-something years…and you leave with no benefits,” said an employee. “It’s sad. If they had a retirement fund and they would take something small out of our pay, then at least we would have something to fall back on.” She added, “That’s the thing everyone’s worried about right now.”

Since housekeeping was outsourced to Aramark, AU employees have witnessed a precipitous erosion of their wages and benefits. (Employee wages are also nickel-and-dimed by fees necessary for the job. Two workers described how they pay close to $1,200 yearly just to park the three or four weekdays they work. With an annual income of below $25,000, parking costs amount to almost five percent of an employee’s yearly take.)

Aramark employees are now fighting an uphill battle to obtain the benefits they once had.

“Housekeeping employees enjoyed incredibly generous benefits,” said Joseph Eldridge, AU chaplain and accomplished human rights activist. “Good health care, free classes through a tuition remission program for themselves and their families, vacation, sick leave, maternity leave,” he said. “But the university wanted to save money and lower costs, and they saw contract work as a viable alternative, so they contracted out food service and housekeeping.”

II. The Representatives

The SEIU has made a priority of organizing custodial employees who work for the so-called “Big Three” – Aramark, Sodexo, and Compass Group. When SEIU came under the leadership of current President Andy Stern in 1996, the union increased its membership by 60% to nearly 2 million. Stern has been an innovator in union organizing, eschewing traditional methods like striking — which has been all but abandoned by the SEIU — in favor of what he sees as more successful tactics.

A hallmark of SEIU’s expansive growth over the past decade has in part been the deliberate transformation of the American union into a powerful political force. In 2008, Stern told NPR’s Neil Cohen that.

“I don’t think anymore that the power of unions comes from its ability to strike. I think it comes from its ability to participate in the political process and to change America in issues that we’ve been talking about, like health care.”

He makes a compelling case. Wage increases, larger representation, and powerful lobbying are undeniable achievements his leadership has helped bring. He asserts that militant tactics and abstract discussions of democracy have all but hindered the progression and growth of unions in an age of corporate mergers, diversified industries, and transnational development. But some of his methods are controversial.

Critics within the labor community claim that SEIU’s largess makes it unrepresentative of its members. According to socialistworker.org, some SEIU branches like United Healthcare Workers disdain Stern’s tactics. They say SEIU’s hunger for expansion leads the distant union power brokers to grow numb to the concerns of members.

Indeed, there’s some evidence that SEIU is pursuing the union’s power at the expense of its rank-and-file. Kris Maher of The Wall Street Journal reports that secret agreements between SEIU and large employers have become popular. The agreements exchange employer-friendly contract provisions for withdrawal of opposition to union organization. Employers are permitted to choose the preferred locations of unionization without the knowledge of effected employees. The result: SEIU expands its membership, employers don’t have to cough up profits for salaries and benefits, and workers are hung out to dry.

Were the workers at AU victim to one of these backroom deals? There’s no way of knowing for sure, as union officials are mum on the issue, but included in the previous contract is a suspicious clause forbidding Aramark employees at AU from striking.

“They can strike if their contract expires and it is not extended,” said an SEIU Local 32BJ (the Local that represents AU workers) representative who spoke without attribution. This, she said, “is often an indication of a good relationship.”

The 32BJ official credited SEIU leadership for pay raises and increased vacation since union recognition in 2001, but Aramark employees at AU bemoan concerns unaddressed by the union.

“We don’t really have a good union, anymore,” an employee said. “The people running it don’t do nothing for us. They can’t negotiate well. I don’t go to some of the meetings because they can never tell you anything good, so I never go. They don’t do much for you, anyway.”

Another employee hoped the union would fight for benefits relating to “wages, retirement, education, classes for English and computers, insurance, more vacation, and a bonus at the year’s end.” Other concerns raised by employees include disabilities, parking costs, and understaffing.

“We are in the very early stages of bargaining and have not discussed wages or benefits,” the 32BJ representative explained. “Workers are updated about the bargaining process one or two times a week” and “union leadership tries to figure out from members their overall goals, but also their bare minimums,” she said. “We are reviewing proposals and will be setting dates to meet again soon.”

Workers are anxious.

“For now, we stay in negotiations. We don’t know what’s going to happen. We’re waiting now,” an AU worker said.

And in a time of uncertainty, campus-wide support is absent.

“The other day I saw an article in the Eagle about one of the ladies in the Eagle’s Nest…I said to one of my co-workers, ‘too bad we never see an article about us,’” another employee lamented. “We need it to uplift our spirits. That would be nice.”

III. Aramark at AU

On the most basic level, employees and students are mutually obligated to one another — to ensure the campus stays clean and to maintain a certain level of respect. But some say student-employee obligations must extend far beyond the bare minimum.

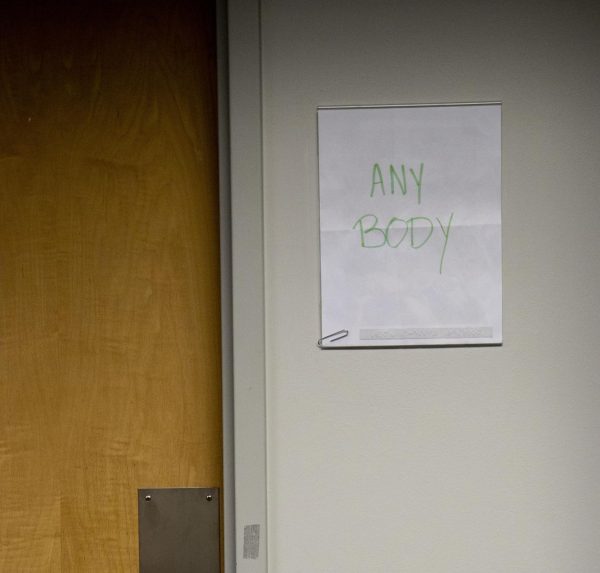

Aaron Montenegro, a member of Solidarity, a student group advocating better treatment for employees who work at AU, has tried to find ways tuition-paying students can pressure the university to do its part for employees.

Twice last year, he brought proposals to open forums with the AU administration: first on his own, and then again with AU’s Community Action and Social Justice (CASJ) Coalition and 1000 signatures. They wanted Aramark employees to be included in the tuition remission program that once allowed employees and their families to take advantage of AU classes and programs.

“They shot us down,” he said. “The administration told the students that tuition remission was something Aramark and the union had to handle.”

The representative from Aramark’s Housekeeping department disclaimed responsibility.

“This is the responsibility of the school to decide on. Housekeeping stays neutral,” she said.

AU also refuses to take ownership of the issue. Last spring, Human Resources VP Jorge Abud told the Eagle that AU’s officials “don’t really have a role” in tuition remission. The remission program, he said, “did not seem to be something that was a strong interest to the Aramark workers.”

The three employees we interviewed for this article expressed support for more education benefits. Aramark employees say student support has been invaluable.

“They help us a lot,” one employee said. “They worked with us to help get us a raise. They are always fighting for us. We are very pleased that they did that. During certain times of the year, they would go out of their way,” she said. “The students really help us a lot and we are very proud of the students.”

Both Montenegro and Rev. Eldridge encourage student outreach to the employees, because it has worked in the past. A few years ago, AU, “organized a sort of living wage task-force to figure out the living wage in DC, which they determined to be around $12. AU requirements were adjusted accordingly,” Eldridge explained.

But until such an initiative is undertaken again, AU will continue to maintain an underclass of employees with fewer benefits and services, struggling for the comfortable life enjoyed by other professors and its more visible workers.

For Montenegro, the fact that a wealthy university doesn’t adequately compensate all of its employees mars the school’s impassioned Methodist commitment to social justice.

“The university gives students tools to realize social justice and effect change abroad,” he said, “but at the same time it ignores possibilities right here on campus.”

Delaney Rohan is a graduate student studying Ethics, Peace and Global Affairs. Jamie Smolen is a sophomore studying international relations and economics.

Students looking to get involved can contact CASJ at [email protected]. The group holds meetings on the first Tuesday of every month in Kay x3333. Solidarity plans on holding meetings and actions in the upcoming months. Students can join the facebook group “Solidarity AU” or contact Rev. Eldridge for more info. Community Learners Advancing Spanish and English (CLASE) is a group that provides English tutoring for many of Aramark’s Hispanic employees. Contact at them [email protected].