A Painful Paradox

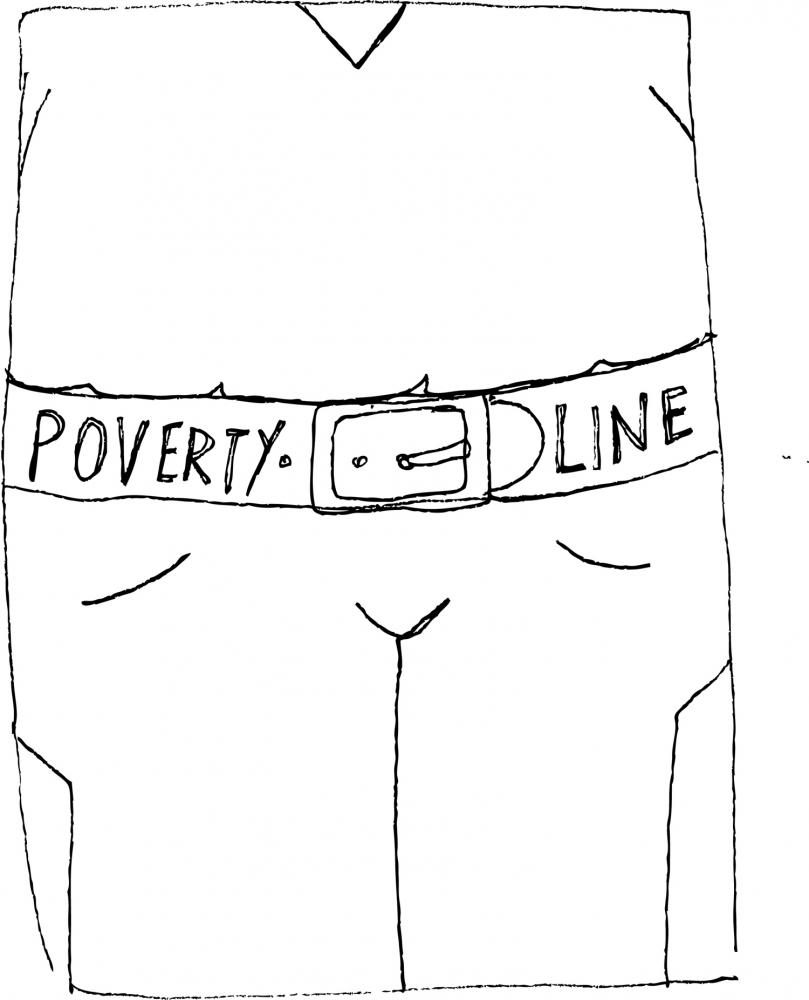

Poverty and obesity sometimes occur simultaneously—in the same city, neighborhood, or even household. Lower-class families are particularly susceptible to obesity because of the added risk factors connected with poverty, according to the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC), a national non-profit working to eliminate hunger and poverty.

The relationship between poverty and obesity has played a part in the on-going health care reform debates. The Kaiser Family Foundation found that among the 46 million people in America who lack medical insurance, about two-thirds earn less than twice the poverty level. Slate’s Daniel Engber calls this “a dense web of reciprocal causality.” In a Sept. 28 piece on this topic, he wrote: “Anyone who’s fat is more likely to be poor and sick. Anyone who’s poor is more likely to be fat and sick. And anyone who’s sick is more likely to be poor and fat.”

The connection is multi-faceted. First, many low-income families face limited dietary options. Healthy, organic foods available to the middle-and upper-classes are not always accessible in lower-income neighborhoods, let alone affordable. Not everyone can fit Whole Foods in their budget. Thus the expense of eating healthy contributes to poor nutrition.

“The ‘Whole Foods idea’ really misses [low income populations] and ignores them for the large part,” said Dr. Robert E. Lynch, a pediatrician from St. John’s Mercy Medical Center, one of the top hospitals in St. Louis.

He said that numerous nutritional challenges result from poverty; struggling mothers, for example, often dilute milk for their kids with water to make it last longer.

Poor nutrition is only part of the problem. In addition, low-income families face limited access to healthcare, poor physical education in public schools, and stress resulting from economic instability. Parents often skip meals in order to feed their children, and then overeat later—which contributes to both hunger and obesity. Lower-income families also have less time to cook meals and exercise.

So these families go to fast-food joints like McDonalds or Burger King and buy high-calorie, sugar-laden meals for their children because they are filling and affordable.

On top of all of this, the media may be exacerbating the problem.

“Parents can try and instill in children some sense of nutrition and understanding,” said Kathryn Montgomery, who directs the Project on Youth, Media, and Democracy through AU’s Center for Social Media. “They are going against a flood of highly persuasive marketing machinery that is teaching the exact opposite.”

She also said that parents are far more detached from the rising digital media culture—a culture that should also be equally responsible for educating young people.

Parents want to feed their children the healthiest foods; children want to eat what they see marketed to them. Often, the desires don’t match up.

The result: children in low-income families have a higher risk of obesity resulting from advertising and tight budgets which forces their parents to put unhealthy food on the dinner table.

Abolishing the fast food media bombardment is a pipe dream, but organizations like Bread for the City are trying to fight the poverty-obesity paradox. For thirty-nine years, they have been providing food, medical care, and legal services in the DC metro area for free.

Operated by volunteers and funded by benefactors, this organization distributes grocery bags full of nutritious meals to struggling families, which include fresh produce. Bread for the City also funds projects in DC that grow produce locally and save money.

It’s a step, but can more progress be made? Lynch thinks so. “I think education is the number one tool,” he said.

“Low-income families ought to think collectively. There are movements to have farmers markets; there are collectives and cooperatives,” Montgomery said. “I will hope that they would join together with other families, because that’s how we get change.”

Sarah Allen is a sophomore studying foreign languages and communication media.