Facing femicide

Mexican Culture Club writes names of “feminicidio” victims to raise awareness

Content Warning: This article contains descriptions of sexual assault

Editor’s Note: Some of the data included within this story was translated from Spanish to English

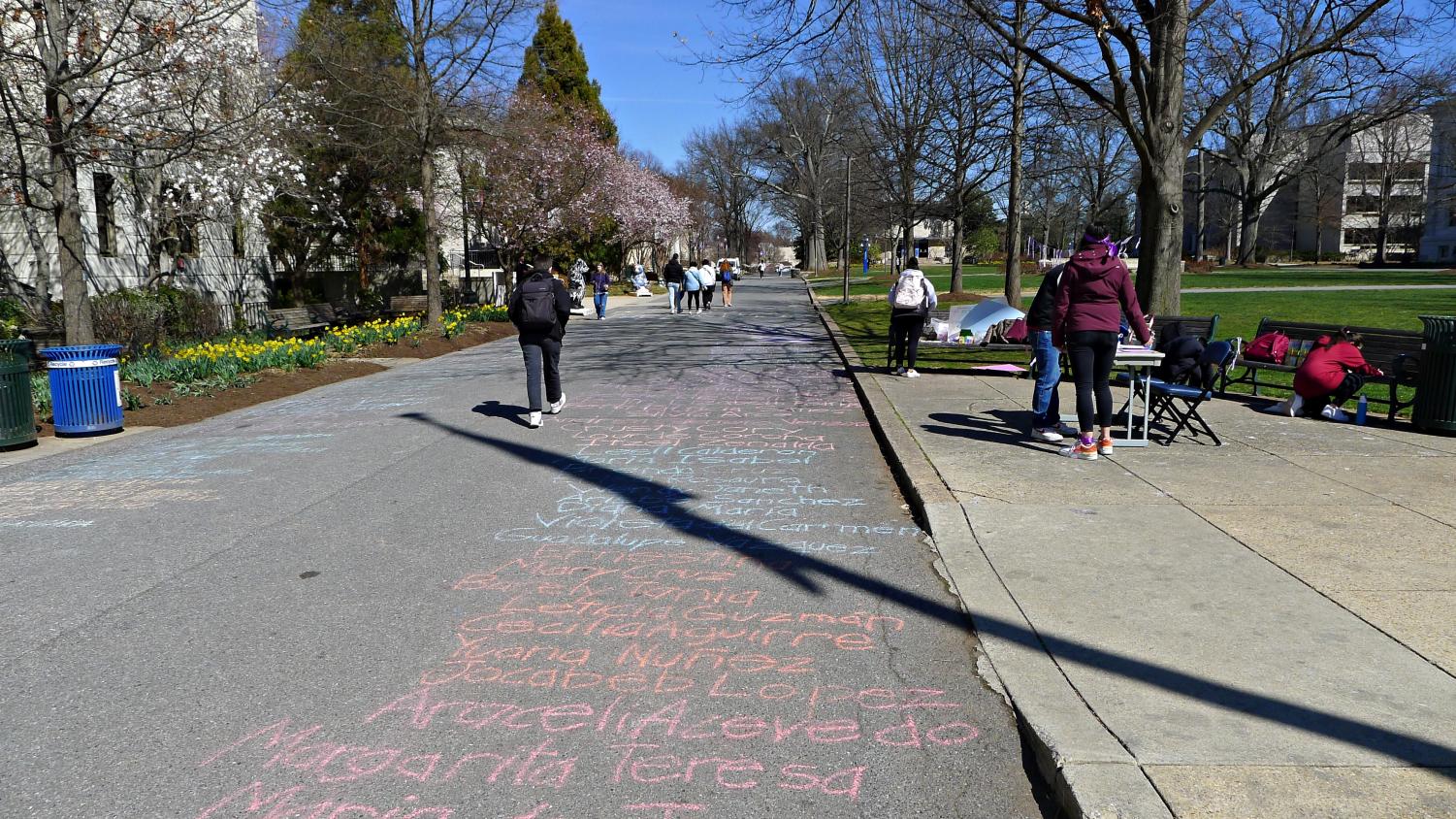

Sofia Guerra was one of several members of the Mexican Cultural Club at American University who wrote the names of victims of femicide on the ground in front of the Mary Graydon Center on March 9.

One of the names on the ground was Guerra’s aunt. Guerra said that about four years ago her aunt, Abril Pérez Sagaón, was killed by her husband.

According to a Feminist Criminology study published in 2021, femicide is defined as “the killing of a female because she is a female.” The study also said that the legal definition of femicides does not include deaths of women due to legal discriminatory practices against women.

Guerra said that Pérez Sagaón’s husband abused her before killing her.

“But she suffered abuse from her husband and there was this case where it got very, very aggressive and he hit her with a bat and almost killed her,” Guerra said. “He broke her skull – trigger warning – and Abril survived that.”

Guerra said that Pérez Sagaón’s husband received a restraining order instead of being sentenced to prison time. Guerra said he then violated the restraining order three times before his arrest.

Guerra said that from prison, he paid a hitman to kill Pérez Sagaón. Pérez Sagaón died on Nov. 25, 2019, after being shot in her car, according to the BBC, who reported on the shooting at the time. Nov. 25 is the UN’s International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, and people were already protesting when Pérez Sagaón was killed.

“Her story, thankfully, went viral because it was on a day where women were protesting just because of this,” Guerra said. “But Abril’s story was lucky to be viral. There’s a lot of deaths and invisible deaths that are not known.”

In an email after the event, Guerra said her aunt was kind, hardworking and extremely intelligent.

The Mexican Cultural Club, of which Guerra is the vice president, wrote the names of about 350 victims of femicide. Members of the club wrote names and encouraged people passing by to write about femicide on a “tendedero,” a Spanish word for “clothesline.” The “Tendedero” Project lasted from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m., according to a March 8 post on the club’s Instagram.

The names represented a part of the people killed by femicide, said club President Sofia Aja. In 2022, there were 948 reported cases of femicide, according to a report by the Office of the Secretary for Security and Citizen Protection of Mexico. Additionally, 2,808 women were victims of intentional homicide.

Aja said that in Mexico, protests occur on March 8, and people share stories about abuse or sexual harassment on a “tendedero.”

“We wanted to create awareness and speak for them [Guerra], like for those who are not here and for those who are not able to speak,” Aja said. “Even if we’re not in Mexico, during the protests and being with these people, we wanted to bring it here.”

The club was able to write the names of victims of femicide in front of MGC by following university guidance, Jasmine Pelaez, the internal communications manager for the university, said in an email.

“As a general practice at AU, our campus community members and student organizations are free to chalk on outdoor surfaces in accordance with our Chalking Guidelines,” Pelaez said.

According to the guidelines, the university lets natural elements clean the chalk. Rain began to wash away the chalk the following day.

Isabela Linares, a senior at AU who attended the event to support her friends in the club, said International Women’s Day, March 8, is often viewed as a time to celebrate the accomplishments of women, but that the day should also be an opportunity for action.

“Everyone’s like ‘We want to celebrate the women, we want to say like, celebrate everything that they’ve accomplished,’” Linares said. “But for us, it’s so much more than that, like we don’t really celebrate it. For us it is a day to fight.”

Linares grew up in Columbia and said she protested against femicide when she lived there.

“The names that you see right now on the floor are just Mexican names,” Linares said. “But if we created a list of all the women that are victims of femicide, around Latin America, the number would just be outrageous.”

According to a report by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, globally, about 47,000 women were killed by a family member or partner in 2020. The report also said that the Americas have seen a 9% increase in homicides in the past decade.

According to the Feminist Criminology study, about a third of female deaths were caused by people known to the victim.

First-year Isabela Diaz wrote on a card as part of the clothesline. Diaz said Indigenous people going missing in both Latin America and North America is an “important thing to think about.”

“There’s a lot of Indigenous missing women who go unrecorded and no one says anything about them,” Diaz said. “So I think a bigger conversation is about Indigenous women and how they’ve always like been exploited, overlooked, unhumanized and all of that.”

According to the Feminist Criminology study, the rate of femicides in Indigenous communities was considerably higher than the rate of femicides in non-Indigenious communities. According to the study this could be due to patriarchal structures in these communities or structural and sociopolitical factors, such as high poverty rates and the war on drugs.

Femicides are part of a larger problem of sexual violence towards women. Sophomore Alanis Umacata-Pacchi said that women are threatened by assault and discrimination.

“As a woman, I feel like we still push through and we still make it out alive,” Umacata-Pacchi said. “Or we still succeed somehow in our story.”

Femicide does not just impact women. It also affects the families of women and communities in which it occurs.

Oliver Arandia, the treasurer of the Mexican Culture Club, said femicide impacts him because of his mother and sisters.

“I don’t think it’s fair that they should have to worry when they just go out to do basic stuff,” Arandia said.

According to a post on the Mexican Cultural Club’s Instagram from March 9, the event was an opportunity to share stories and stand in solidarity with women.

Guerra said her experience with femicide and the murder of her aunt caused her to want to show others the reality of gender-based violence.

“I’m using my voice to tell her story, to make awareness of this,” Guerra said. “It’s stuff that you see on a newspaper and you feel that it’s so far away. But it’s really not that far away. Gender violence is something that women experience daily.”

Neal Franklin (he/him) is a senior studying Foreign Language and Communication Media. He enjoys singing in the AU chorus, hiking and playing board games.

Kalie Walker (she/her) is a senior studying journalism. Outside of AWOL, Walker enjoys crocheting, writing and swimming.