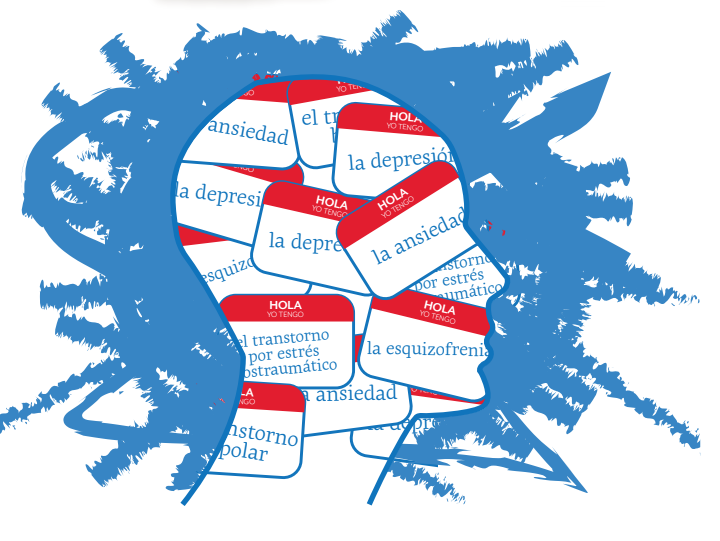

Mental Borders: Mental Health Challenges in the Latinx Immigrant Community

Immigration status plays a large role in mental health, but barriers often prevent needed treatment.

This story first appeared in the Fall 2019 print edition of AWOL.

Tatiana Murillo came to the U.S. from Nicaragua at 11 years old with hopes of better opportunities and a chance to “be somebody” if she worked hard enough.

She didn’t know that “somebody” would become paralyzed by anxiety, weighted by depression and changed by trauma.

Murillo, now 29 and a graduate student at American University, learned she was undocumented in middle school. With that came a warning to keep quiet about her status and how she came to the country. She could be deported by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, her family told her.

“I began to feel scared about sharing [my status] publicly,” Murillo said. “Hearing about ICE raids really created a lot of anxiety in me. I really didn’t want to go out.”

In her fear, she inaccurately associated local police with ICE. Getting in trouble meant police. Police meant ICE. ICE meant deportation.

She tried to lay low. Murillo became shyer and more introverted.

In high school she began to realize how her status restricted her as she watched friends pursue opportunities she couldn’t. She became depressed and began losing motivation and self-esteem. She estimated that she only attended about three months of the ninth grade.

In the years afterward, Murillo said she continued to struggle with anxiety, depression and the traumas related to her status in the U.S.

She is now protected under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which gives work authorization and temporary protection from deportation for unauthorized immigrants who came to the U.S. as children.

But Murillo is still living in uncertainty. In September of 2017, President Trump announced that he would rescind DACA, which led to lawsuits. The continuing court battle and impending Supreme Court decision in September 2020 will determine the fate of Murillo and the hundreds of thousands of people covered under DACA.

“I’m so afraid of what could happen tomorrow, and it’s not just me, but everyone around me who is undocumented,” Murillo said.

Constant stress from the fear of being deported is considered a post-migration trauma and can have grave effects on a person’s mental health.

A 2019 study from the Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health found that pre- and post-migration trauma for Latinx immigrants led to a wider variety of mental health issues than the trauma for those classified as refugees, a label which many say is politically-driven.

Pre-migration trauma, such as exposure to violence and poverty, had “destructive, long-term mental health consequences,” according to the study. Post-migration trauma, such as anti-immigrant rhetoric and stress relating to adapting to a new culture, increased the risk for psychological distress, particularly depressive disorders.

Many things that are unique to the experience of Latinx immigrants contribute to their mental health concerns. Despite the prevalence of these issues, the conversation about mental health in the community is limited, and cultural and systemic barriers make it difficult to get treatment. However, efforts to address these issues and increase discussion may help improve the situation.

Gabriela Romo, a psychologist in Chevy Chase, Maryland, sees the direct and indirect connection between mental health and immigration every day with her clients, about 85% to 90% of which are Latinx.

Through therapy sessions and psychological evaluations for immigration cases, all of which are offered in English and Spanish, Romo sees many cases of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorders and depression in her clients. They often have issues adjusting to the new culture and language, dealing with separation and losing friends and family through the immigration process, according to Romo.

“Suddenly they feel like they’re very isolated,” Romo said. “They lose a sense of community, that emotional and social support.”

The current political environment brings another layer of fear and anxiety that Romo said she hadn’t seen before Trump started campaigning for president in 2015. Discrimination, microaggressions and targeting people with certain profiles are a “side effect” of the political environment, according to Romo.

Of the foreign-born Latinx population, 57% say they have “serious concerns about their place in America” with Trump as president, according to a 2018 report from Pew Research Center. The report found that of the total Latinx population, about four in ten Latinx people have experienced discrimination, been criticized for speaking Spanish in public, been told to go back to their home country or been called offensive names in the past year.

Such aggressions affect all Latinx people, not just those of a lower socio-economic status, Romo said. One day, she was speaking with her sister on the phone in Spanish, and a neighbor told her to go back to her country.

“It’s like the #MeToo movement among the Latinos,” Romo said. “Racism was already there, but it was politically incorrect. Now it’s normalized.”

Romo said these kinds of social targeting takes years to heal from.

Before Trump, the situation for those with legal statuses in limbo wasn’t any better, Murillo said. But there weren’t constant reminders through the news and anti-immigrant rhetoric about the consequences of their status.

Many in the community are trying to lay low and do not go out as much as before, said Murillo, who is also the director of finance at Identity, an organization serving Latinx youth and their families in Montgomery County.

When Trump started campaigning, Romo noticed an increase in the number of clients for both therapy and evaluations for immigration court. After he was elected, she saw a spike.

Diego Uriburu, executive director at Identity, has noticed the increase in anxiety from the political climate as well.

“Folks who have not considered getting access to services before are more willing,” Uriburu said. “[The] current climate has led to a lot more people looking to access services.”

But not all are able to get the services they need. In 2018, 33% of Latinx adults with mental illness received treatment compared to the national average of 43% for adults, according to the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

The cost of mental health services is the most commonly reported reason people don’t receive treatment, according to a 2015 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration report. Approximately 53% of the Latinx population needing mental health services named cost as the reason for not receiving those services.

“If they’re making minimum wage, obviously their priorities aren’t mental health, or at least that’s what I’ve seen,” Murillo said.

One session of therapy usually costs between $70 to $150, according to Romo. Most patients need between eight and 12 sessions.

Health insurance is “another can of worms,” Romo said, because many mental health practitioners do not take Medicaid, and many immigrants lack health insurance.

In 2014, almost half of the foreign-born Latinx population without citizenship didn’t have health insurance, according to Pew.

Other barriers help explain the unmet need for treatment.

“Culturally, in Central America and other [Latin American] countries…access to mental health services are seen for only extreme cases,” Uriburu said.

A big factor in this is that issues are typically handled within the family or extended family in Latinx culture, according to Romo.

“Seeking help outside of your family unit or opening up outside of your family unit can be very shameful,” Romo said. “There’s a sense of shame or weakness or that you are alone.”

This perception is stronger when combined with “machismo,” a cultural term to describe an attitude of traditional masculinity. It makes it more difficult for men, particularly older men, to seek out treatment, according to Uriburu.

There’s also a stigma that those who seek mental health services are “crazy,” Romo said.

Murillo has experienced this as well. Culturally, there’s a sense that people with mental health issues should “just get over it” and “move on,” she said.

About 4 years ago, Murillo went to therapy for a year for a “mix of things,” Murillo said, part of which was trauma related to her immigration status. But her family still doesn’t know. As an adult, Murillo felt she didn’t need to consult with family, and she didn’t want her mom to worry that something was wrong with her.

While out with her mom one day, Murillo ran into her therapist and introduced her to her mom accordingly. Other than that, they’ve never had a conversation about Murillo’s mental health or her time in therapy.

“In general, this society is not ready to talk about mental health. I think there is a lot of ignorance,” Romo said. “We think this a stigma of the Latinos but also generally speaking, too.”

Such barriers are weakening with the younger generations, Uriburu said.

“Young people tend to acculturate faster, and they understand [mental health treatment] is good for them,” Uriburu said. “They have a lot less barriers to mental health.”

Urban areas like D.C. also have more resources than their rural counterparts, Romo said.

Romo believes the mental health situation for Latinx immigrants can still be improved by having more affordable options for those with Medicaid or no health insurance at all.

Increasing the accessibility of services, especially by offering services in Spanish, is important, according to Romo. Trying to talk about personal issues and feelings is difficult, Romo said, and trying to do so in a non-native language adds another layer of difficulty.

Only 5.5% of therapists provide services in Spanish, according to a 2015 survey from the American Psychological Association released in 2019.

Speaking Spanish does not solve all concerns. Non-Latinx healthcare professionals may not understand complex cultural issues, according to an analysis from the National Alliance on Mental Illness on the mental health of the Latinx community.

Cultural differences may lead to misunderstanding and misdiagnosis. While patients may describe symptoms of depression, doctors unfamiliar with Latinx culture may not recognize them as such, according to the analysis.

For example, patients may describe themselves as having “nervios,” which in English means having “nerves” or nervousness. Doctors unfamiliar with the effect of culture on mental health may interpret this as a more simple state of nervousness rather than a more complex symptom of depression.

Professional and medical intervention is not the only way to address mental health, Uriburu said. The majority of people who come to Identity can sufficiently address their mental health concerns through other interventions like group conversations, time for introspection and even games for young people.

Many want a larger conversation about mental health. Conversation about mental health and coverage in the news can lead to changes in policies of all issues because mental health affects every aspect of life, Romo said.

When patients come for their evaluations, Romo often has to explain that she’s not showing the judge they are “crazy” but rather that they’ve experienced “emotional hardship” that should be considered in their immigration cases.

“They have resiliency. They don’t know they have it. That’s part of my job, to make them realize it,” Romo said. “You’ve gone through a lot to get here. Let’s leave those ghosts behind…This is your reality now.”

Savanna Strott is a junior studying journalism with minors in creative writing and Spanish.