Lonely Streets: Transgender and Homeless in the District

Ashanti Carmon, a transgender woman, was killed in Prince George’s County on March 30 of this year. Homeless and rejected by her family for being transgender, Carmon began selling sex at 16 years old. It was on Eastern Avenue, while walking back to her boyfriend’s home, that she was shot multiple times and killed.

In 2018 alone, advocates of The Human Rights Campaign tracked 29 deaths of transgender people in the United states. Eighty-two percent were women of color.

“We need to step up and speak out if we’re going to expect people to agree to help,” said Dennise Tibbs, a transgender woman and employee at Casa Ruby. “There are people who will ignore you and look the other way. It’s sad that people are out here on the streets, and they don’t even bother acknowledging us.”

The LGBTQ community faces adversity with homelessness and unemployment. According to a study published by the University of Chicago, LGBTQ youth are 126 percent more likely to experience homelessness than non-LGBTQ youth. The District’s 2017 Homeless Youth Census found that 31 percent of young people experiencing homelessness “identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, or queer/questioning,” and 6 percent identified as transgender.

George Membreño, director of youth housing at the local nonprofit Supporting and Mentoring Youth Advocates and Leaders, said there are multiple reasons why youths end up homeless.

“One of those [reasons] is family rejection,” Membreño said. “We’re looking at kids who have been kicked out of their homes because of their gender and sexuality expression and identity. In those situations they are kicked out disproportionately more than their heterosexual peers.”

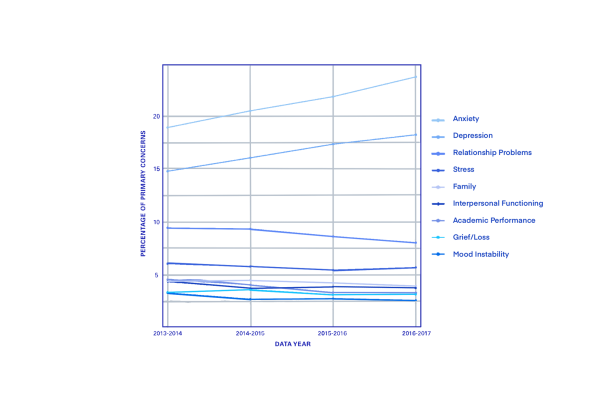

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, stigma, rejection, and violence can often affect the mental health of LGBTQ youths, who are three times more likely to experience mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety disorders. The Alliance also states that suicide is a leading cause of death for LGBTQ people between the ages of 10 and24, and between 38 and 65 percent of transgender individuals experience suicidal thoughts in their lifetime.

“We know that systematically, kids who are part of the community are discriminated against much higher and so there are higher rates of depression, higher rates of substance abuse, and higher rates of mental health needs because of that rejection,” Membreño said.

Casa Ruby is the only bilingual LGBTQ organization that provides a drop-in center and youth transitional housing program. Homeless LGBTQ youth are given the opportunity to have a safe space with food, shelter, with other social services such as case management and programs that help youth attain a government issued I.D.

Noura Moira, a transgender woman and employee at Casa Ruby, explained her experience with homelessness.

“You can’t talk to someone if they don’t understand you,” Moira said. “I talked to so many people, no one really understood what I’ve been through. You really feel alone. That makes you feel down, like suicidal. You think your life has ended.”

Moira, an immigrant from Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, escaped 15 months of torture in Saudi Arabia after coming out as transgender. After hours on a plane, where her wounds prevented her from leaning back in her seat, she managed to enter the United States as a visitor.

Moira spent years escaping her family and her husband’s family, who sent people after her to kill her in Arkansas, forcing her to flee to Virginia. Her ex husband, who Moria met and married in Virginia, was sent back to the Middle East by his family to endure conversion shock therapy so he could be straight.

“It was so scary having to escape,” Moira said. “You need to smile so that no one suspects something. If they [security and officers at the Saudi Arabia airport] suspect something they cut you or kill you.”

Moira continued to explain that if the United States did not accept her asylum request, she would be sent back home and killed.

“Even when you arrive to the United States, you need to talk to the officers and pretend everything’s okay and you’re there to visit because you don’t want to go to jail,” Moira said.

“If you tell [customs] you want to apply for asylum they will put you in jail for–I don’t know how long. If they believe you after the investigation they will release you, but if they don’t believe you and send you back that’s the end of your life, that’s it.” Moria said.

Bianca Carter, a transgender woman also employed at Casa Ruby, also ended up homeless because of family issues.

“My father put me out at 17 because he couldn’t deal with me being transgender and me living my truth,” Carter said. “He didn’t feel comfortable, and I think that was the biggest thing, but I felt comfortable.”

Tibbs explained how Casa Ruby helped her find a home and a supportive community.

“For me [Casa Ruby] is a stepping stone, but it’s a big stepping stone because I’m not only using my resources, but I’m using the outside world to help me get further,” Tibbs said. “I’ve been held back by my own family for so long, I don’t even bother talking to them on the phone.”

LGBTQ youth can face rejection and violence at home. According to the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence, a 2015 survey among transgender respondents found that 47 percent of respondents were sexually harassed, 9 percent were physically assaulted in the past year because they are transgender, and 65 percent have experienced homelessness due to domestic violence.

Annie Miller, another resident at Casa Ruby, said it was a place to go when there was no where else to turn.

“I used to stay with my parents but I didn’t like staying there because there was no support,” Miller said. “It was basically a roof, but there was no support and no guidance and that’s what I was looking for. To this day I’m still trying to do it.”

Casa Ruby fills a void for the homeless LGBTQ community, as it is difficult for them to find shelters. Moira, like many other transgender people, faced discrimination in shelters before she found her way to Casa Ruby. As a woman above 30 years old, many of the youth LGBTQ-friendly housing was not accessible. Transgender individuals often face discrimination in shelters because most homeless shelters are divided by gender.

When Moira tried a woman’s shelter she found a note on her locker that made her feel uncomfortable and fear for her life.

“They wrote ‘this is a woman’s shelter, not for faggots, leave before we kill your ass,’” Moira said. “I looked at the note and said, okay let me go and finish my job first.”

After work, Moira packed her things and left for another shelter.

“I went to another shelter called Patricia Andy” Moira said. “The police came and did an investigation, but nothing really happened.”

Carter found that Casa Ruby was essential to her safety and success in the future. Finding a shelter that is LGBTQ friendly can allow members of the community to focus on employment and moving forward in their life once they feel safe.

“It was helpful, because I was on the streets for a long time,” Carter said. “When I got in here, and I got into the houses I felt so much better. I could take a shower, I could go into a house, lay my head down, and be safe.”

According to the Center for Transgender Equality, one in five transgender people have been discriminated against while seeking housing. Carter expressed that it was harder to be homeless as a transgender woman because people assume homeless, transgender women of color are sex workers.

“Being on the streets isn’t the easiest thing,” Carter said. “You have one stigma that you’re a trans black woman and then you have another one that everyone thinks that you are a prostitute to get your money.”

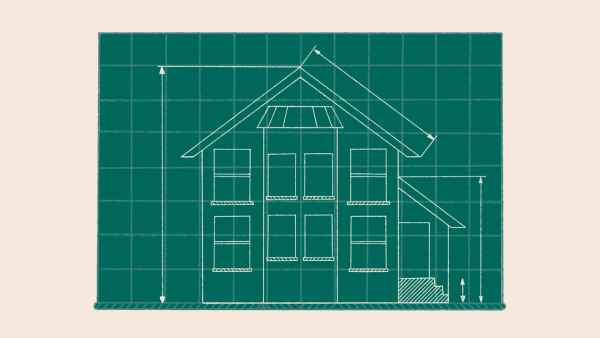

Affordable housing is difficult to find in DC. A one bedroom home averaged $395,500 according to trulia.com and the average rent of a one bedroom apartment is $2,139. For a person that makes $2.50 an hour, like Carter, this is not affordable.

“It’s real hard in DC money wise,” Miller said. “Trying to find affordable housing is really hard. Most of the apartments that I’ve seen or know about are $1,000 and up. Unless you want to live in a bad area where you have to watch your back or not feel safe.”

Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 does not include sexual orientation. It’s remained federally legal for employers to discriminate based on sexual orientation. Although the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission produced guidelines that Title IV does protect sexual orientation, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures many federal courts decline to interpret it that way.

Nineteen states, D.C., and Puerto Rico outlaw discrimination by private and public employers based on sexual orientation through state law. Although there are state laws prohibiting discrimination, there is no federal law that protects the LGBTQ community from employment or housing discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Dennisse Tibbs graduated high school with a 4.0 GPA and graduated from Job Corps in Southwest DC.

“I have faced discrimination in the job market, that’s why it’s been hard to find employment so far this year,” Tibbs said. “Although I’m trans, I feel like I should be respected by my pronouns.”

Transgender individuals can face work discrimination when it comes to employee work benefits, pronouns, and hiring practices. Transgender people can get their ID legally changed to their preferred gender and name, but this can cost more than $55–more than many homeless youths can afford.

“My ID might say something else, but deep down this is not who I am. So it shouldn’t even matter what my ID says or my Birth Certificate says,” Tibbs said. “At the end of the day I am who I am and if you can’t see that I can’t work for you. You have to respect everybody.”

LGBTQ youth that do end up homeless often face discrimination and violence. The Humans Rights Watch found that since 2013, 128 transgender and gender-nonconforming people have been killed in the U.S.. Bianca Carter expressed the struggle against violence she sees within her community.

“I would say the ‘T’ part of LGBTQ, gets the most crime and the least justice,” Carter said. “The feminine gays, and the gay men can kinda get a pass because they can go out on the street dressed like a man and still act feminine. People see a man on the outside and really don’t care. They see a transgender woman and they clock you and say that you’re born a man. Either they accept you, or they want to fight you. It shouldn’t be like that, but it is. I wish it were better,” Carter said.

Carter continued to explain that it’s not enough for her to feel like a woman, she feels pressured to appear as a cis woman to protect herself from violence.

Carter said, “Some men allow us to be transgender women and live our truth. Some men just don’t like it at all and they will kill you. That’s the scariest thing about it. I feel like I have to look like a woman every day, and I have to look passable as a woman everyday because if I don’t someone’s gonna try to hurt me.”

Carter had multiple experiences where she felt like she had to conform to stay safe. Carter recalled an experience on a bus in Northeast D.C. where a man spit on her and said “I don’t like transgender women–what are you gonna do.”

“Even if we don’t get accepted as one, we should be accepted as something rather than nothing. We are human, just like everybody else,” Tibbs said.