Campus Battlegrounds: Testing war chemicals at AU

American University has positioned itself as a leader of environmental sustainability among college campuses. However, buried underneath the foundations of the campus are the remnants of one of the nation’s largest Formerly Used Defense Sites.

McKinley Hall, where the School of Communication now resides, was the home of a chemical testing lab during World War I. It was not the shiny new building that students know today. During WWI, it was an unfinished, forlorn building on a fledgling campus.

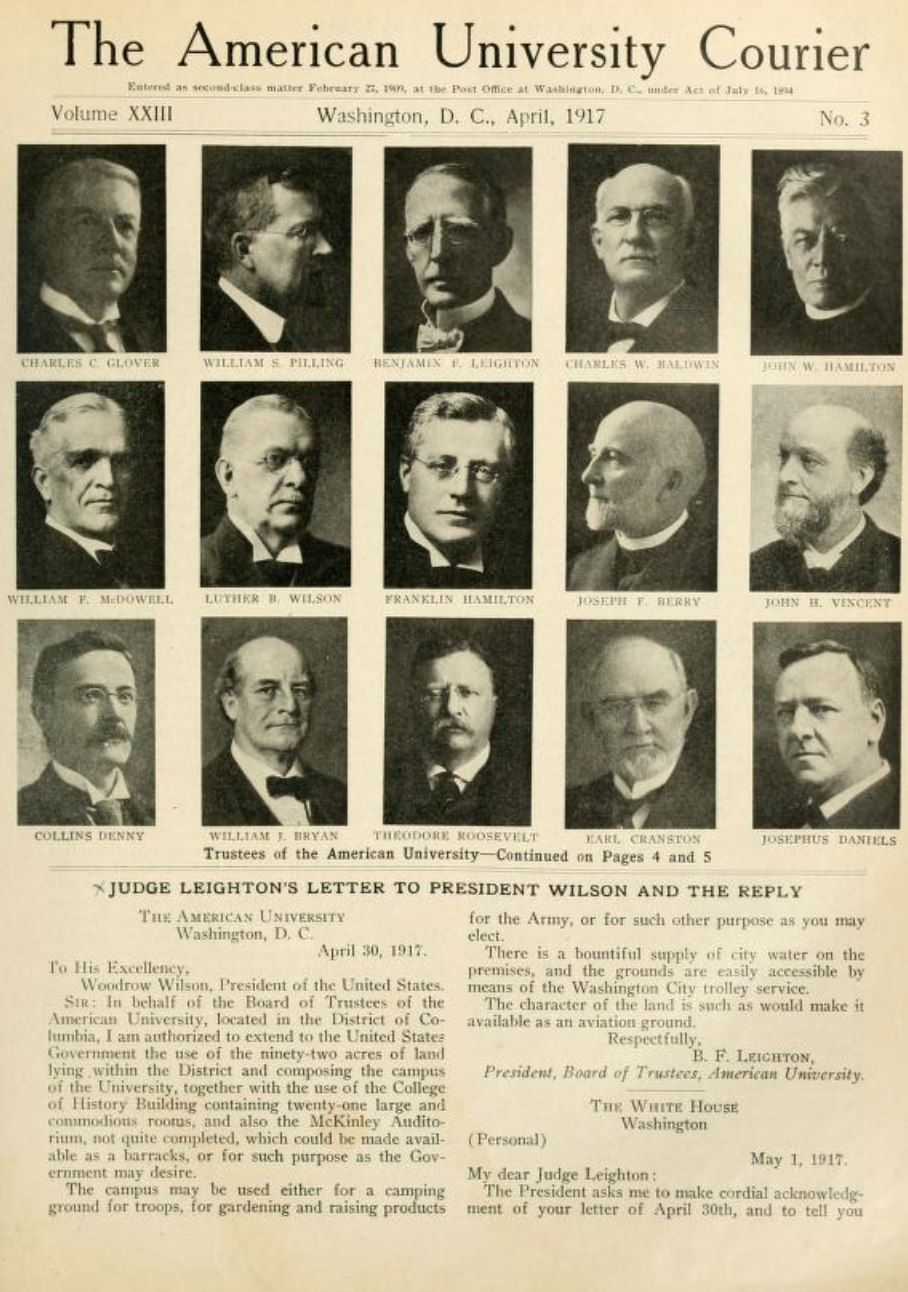

The 1900s were a precarious time in AU’s history. When WWI started in 1917, AU was still a struggling institution located in a place that was undeveloped. The University opened its doors with only 28 students, five of whom were women.

The board of trustees reached out to Woodrow Wilson in a letter offering up the university “to be used as the purpose of the Government may desire. The campus may be used either for a camping ground for troops, for gardening and raising products for the Army, or for such other purpose as you may elect.”

Secretary of War Newton Baker accepted the offer and created the American University Experiment Station, the largest chemical weapon facility in the nation.

Concerned about Germany’s use of toxic gases in WWI, both America and Europe were in a chemical arms race to defeat German forces before they completely harnessed the usage of poisonous gas. At the beginning of the war, the United States lacked the capacity to make chemical weapons or defend itself against a chemical attack.

The Bureau of Mines was the only government agency with the resources and knowledge to help America defend itself against German gas attacks. The US Chemical Warfare Service evolved out of the Bureau of Mines.

When WWI ended, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers gave the land back to AU, including the unfinished building called the Mary Graydon Center. The Mary Graydon Center was supposed to become the new chemical testing lab.

Today, the Mary Graydon Center is the epicenter of campus life. However, neither the origins of its creation, the intended purpose of its use, nor the history of the McKinley building were conveyed in the End of Semester Update memo released on May 2, 2014, from President Neil Kerwin. One of the few university-wide communications that mentioned anything regarding the American University Experiment Station. It was a seemingly innocuous memo about the overall outlook of campus activity, which ended with the report from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. It briefly mentioned that the corps was continuing an investigation in Spring Valley and honing in on American University-owned property at 4825 Glenbrook Road.

At the time the memo was released, 160 pounds of glassware and seven pounds of metal debris, related to the American University Experiment Station had been removed. This project was scheduled to finish in the spring of 2015. But by mid-summer, it was evident that the process was going to take longer than anticipated. Kerwin released another memo on July 24, 2014, extending the timeline to the summer of 2017.

These memos were signs that something was awry with the project. The limited information and historical context presented problems for the administration and the AU community alike. On December 1, 2014, another memo was released. This time it was from the President’s Chief of Staff, David Taylor, who offered only slightly more information about the Army Corps of Engineers’ activities. It stated that they had been conducting cleanup operations for more than 20 years to remove WWI material and that the presence of the chemicals dates back to 1917-1918.

However, the cleanup is not the only thing that goes back 20 years.

Officials from American University reached out to the Army Corps of Engineers in 1986 “to inquire about the possibility of chemicals being buried on campus and potential waste left behind that maybe we need to worry about,” according to Dan Noble, Baltimore District of the Army Corps of Engineers’ Spring Valley project manager.

Documents were searched, but nothing material emerged. This predates the Corps’s cleanup efforts on AU’s campus, which started in the late 1990s, by about 10 years.

The local community is consistently informed about American University’s history and the progress made regarding cleanup. The Army Corps of Engineers sends out a newsletter to every private household in the boundary of the Formerly Used Defense Site two or three times a year. This includes roughly 1,300 households. There’s also a Restoration Advisory Board comprised of community members, regulators, and a representative from American University, said Chris Gardner, an official in the corporate communications office of the Baltimore District of the US Army Corps of Engineers. The Restoration Advisory Board meetings are held every other month.

Despite American University’s involvement on the Restoration Advisory Board, communication about the cleanup to the campus population remains sparse. While cleanup to date has not resumed, and no other memos have been released, issues still arise. The groundwater in two well locations located in the south campus, Glenbrook Road area within the Formerly Used Defense Site contains levels of arsenic or perchlorate above Environmental Protection Agency standards.

Perchlorate is common at military bases in the production of rocket fuel, missiles, fireworks, flares, and explosives. It can be speculated that there was testing of rudimentary rockets at the American University Experiment Station but very little information exists on that project.

In Spring Valley, this groundwater is not used as a source of drinking water. While the Army Corps of Engineers has accepted responsibility for the contaminated groundwater, the path forward remains unclear. Monitoring of the groundwater will continue until a resolution is reached.

To date, there has been no documentation found that could identify all of the chemical testing pits on AU’s grounds.