Finding Common Ground Through the Arts: the Cato Institute’s First Exhibit

On Thursday, April 11, the Cato Institute opened its first ever art exhibition titled “Freedom: Art is the Messenger.” Cato Institute, a think tank centered in downtown Washington DC, is a public policy research organization dedicated to the principles of individual liberty, limited government, free market, and peace.

The new art exhibition is meant to provide a space for people to discuss their differences in a common and calm space. When the guests entered the event, they were given a booklet of the art displayed along with a pocket Constitution and Declaration of Independence. This established an emphasis on freedom and human rights, which the Cato Institute intended the guests to focus on during their visit at the exhibit.

“If we can cool the temperature a bit, we may discover that while we have sharp and principled ideological differences, we may share the same values goals, and hopes,” Peter Goettler, President and CEO of Cato Institute said. “It is important to convene over common values, like freedom.”

There were over 2,000 entries for this exhibit, and only 90 pieces of art were shown. The gallery filled two floors with pieces by many different artists. All of the pieces were fairly recent, spanning from the late 20th century and early 21st century.

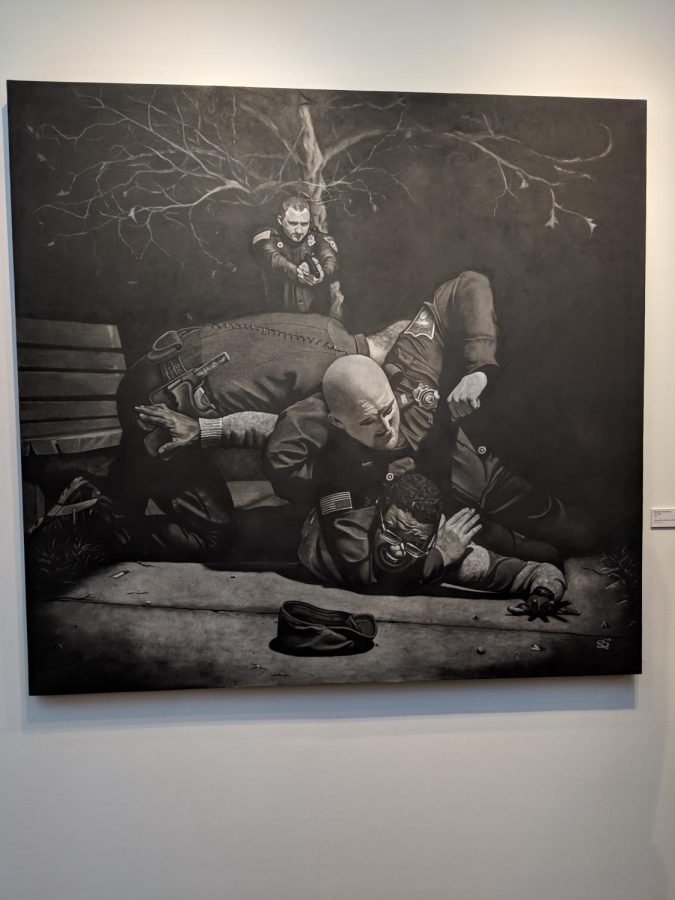

There were three awards and several honorable mentions given to the works displayed. Shanden Simmons, the first place prize winner, created an image of police brutality through charcoal titled “The Profile.” The image depicted two white police officers tackling a black man, along with another white police officer aiming a gun towards the black man.

“This is something that is in a lot of conversations, but not enough conversations,” said Simmons. “[This shows] how contemporary history reoccurs.”

Many attendees lingered in front of “The Profile.” This piece seemed to have the greatest effect on the members of the crowd.

“This makes me want to look away, it is so powerful,” said a woman walking by the painting.

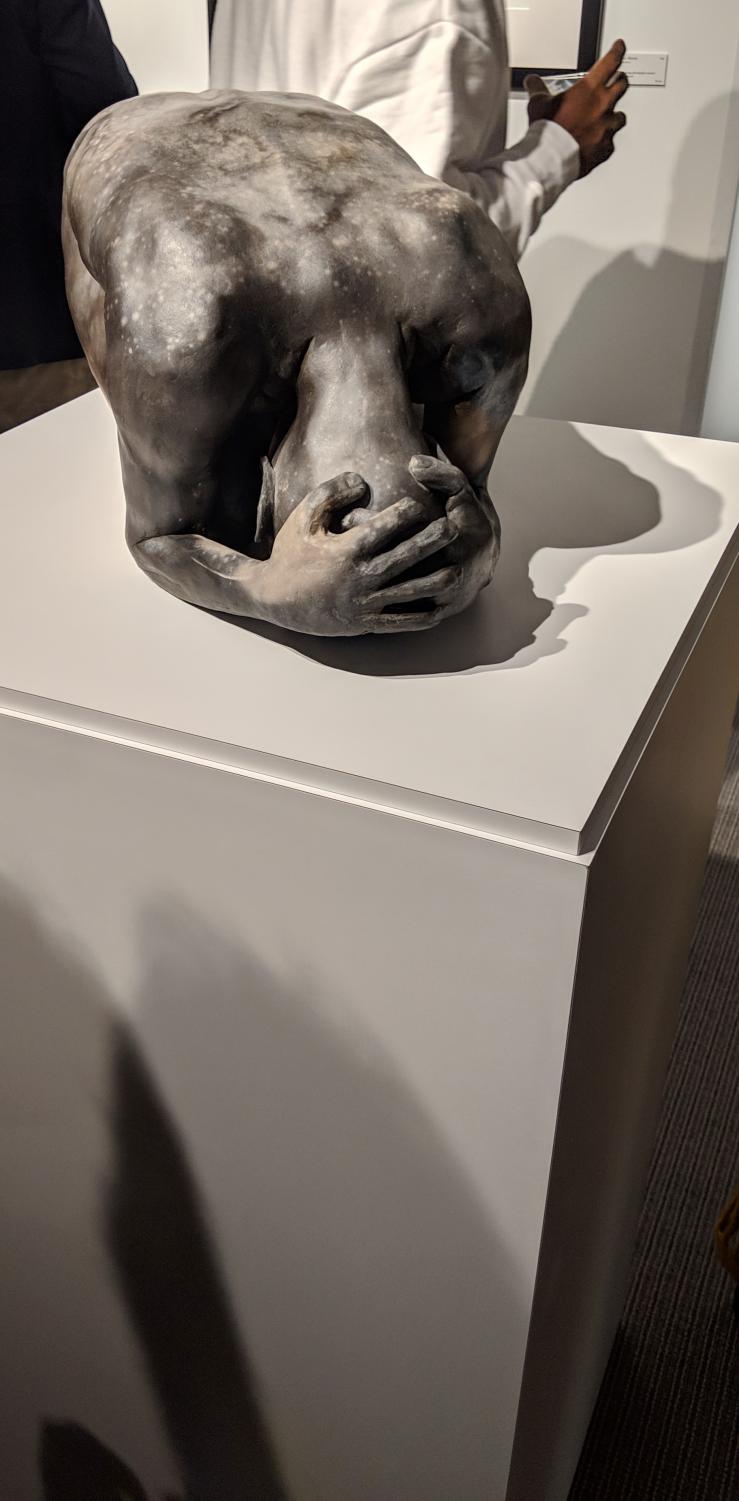

Christopher Corson, a contributing artist to the gallery, created a sculpture of a figure in a downward fetal position with the hands holding its head. This piece was created with pit-fired ceramic.

When asked what specifically inspired him, he sighed and said, “a lifetime. I am a proletariat. I have always felt like the underdog. My feelings came out in this piece.”

Other pieces, like Simmons’ and Corson’s work, focused on the idea of a lack of peace in their own personal environments, their communities, and/or at a national level. All of the artwork depicted the need for freedom and peace and the hardships that come without them.

This gallery will be open to the public every day from April 11 to June 14.

The curators of the exhibit, Harriet Lesser and June Linowitz, stressed the importance of public discourse and how this gallery can be used as a tool to facilitate it. This exhibit with the Cato Institute, they said, provides a bridge for a conversation between opposing views. Freedom is a topic that everyone can agree with.

“Art and freedom, after all, have always been allies,” said Lesser.