SPA gallery shows injustice of juvenile imprisonment

Photographs of incarcerated youth are now on display in the halls of the School of Public Affairs at American University, showcasing images from dozens of adolescent detention centers across the country.

The photographer, Richard Ross, spoke to a crowd of students, faculty, and visitors in the Kerwin basement on February 6 about his work with these incarcerated youth.

“These are the loneliest kids on the planet,” Ross said.

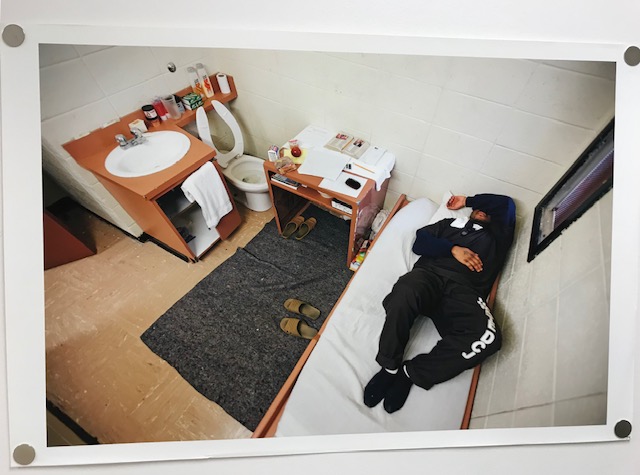

The photographs depict the reality of the American juvenile justice system, showing image after image of stark cell walls looming over youth ages 10 to 17 years old in jumpsuits as they cover their faces.

Each one features a snapshot into the lives of these adolescents and comes with an excerpt of their stories. The youth are shown laying in their beds, standing in isolation cells, and even praying.

Abuse and poverty are common themes in many of the incarcerated children’s stories, with the majority serving time for nonviolent crimes.

“I got kicked out of school for partying and truancy. I use meth,” reads an excerpt from the story of 15-year-old C.T. “They have had me here for two weeks. I think they keep me here because they think I am at risk of hurting myself.”

Ross said he is deeply passionate about reforming the criminal justice system for adolescents. He spent six years building photo evidence of the American juvenile justice system that he now showcases in university museums across the country.

Ross’ project started at the Juvenile Detention Center in El Paso, Texas, where he began talking to a juvenile inmate with limited English.

“I realized that I was the only one talking to him,” Ross said. “I had a responsibility in my life to not only do well but to also do good. So I decided that these kids were the people I was going to give a voice to.”

After that initial interaction, his work became an all-consuming mission, Ross said. The process began with entering the detention centers, which was no easy feat, according to Ross.

“[It took] emails, calls, calls within calls, and even court orders in some cases,” Ross said. “I had to convince the administration that we were on the same page in terms of trying to get better outcomes for these kids.”

Once inside the cells, Ross has a very specific process to make the kids feel comfortable. He knocks on the door first and asks permission to come in. He then takes off his shoes and sits on the floor of the cell. Ross said he ensures that his actions do not make the children feel uncomfortable and provides them a sense of control over the situation.

“It gave the kid power over me, a power that’s visual,” Ross said. “When they see an old white guy sitting on the floor, it’s totally unique for them. They had their shoes off when they were in the cell, so why shouldn’t it be at least a code of equality for them?”

Many of the adolescents opened up to him after that, clinging to the opportunity to communicate with someone who wanted to listen to what they had to say, according to Ross.

Ross said how the American criminal justice system “criminalizes normal adolescent behavior.” He now uses his work to push for policy changes all around the country.

“Kids in middle school, it’s a world of trying to fit in, it’s a world of peer pressure,” Ross said. “Especially if a kid comes from a world of deprivation. If they’re walking by a table and see an iPhone someone forgot, it’s taking an opportunity that normally isn’t there for them. In some cases, it’s taking food because they come from a family where there’s no food in the house.”

Unlike America, other countries tend to only imprison youth for more serious charges, Ross said. When photographing in Canada, every juvenile that Ross met had committed a serious, violent crime. There were none there for minor offenses,

Ross said the high rates of youth incarceration in America are due to heightened politicization of these issues.

“It’s real easy to have a political campaign that says, ‘I’m hard on crime,’ or attack your opponent as ‘soft on crime’ rather than saying ‘I’m smart on this issue,’” he said.

Ross’s project has helped spread awareness about this issue all over the country. He plans to build a nonprofit organization based on this movement in order to encompass all the work he is doing.

Ross said he cannot keep doing it alone because the amount of work involved is “overwhelming”. He is still in the process of looking for an assistant, and half-jokingly asked AU students in the audience to apply.

As for his philosophy surrounding activism, Ross said, “Nothing’s impossible. Doing this work is difficult, but not doing this work if you feel like you can make a difference is immoral.”

Ross’s photos will remain in SPA until March 5.

Ross’s Social Media Links:

Twitter: @juvenileinjust

Instagram: @juvenileinjustice

Facebook: @juvenileinjustice

Grace Vitaglione (she/her/hers) is a junior from West Virginia studying journalism at American University, with minors in Creative Writing and Spanish....