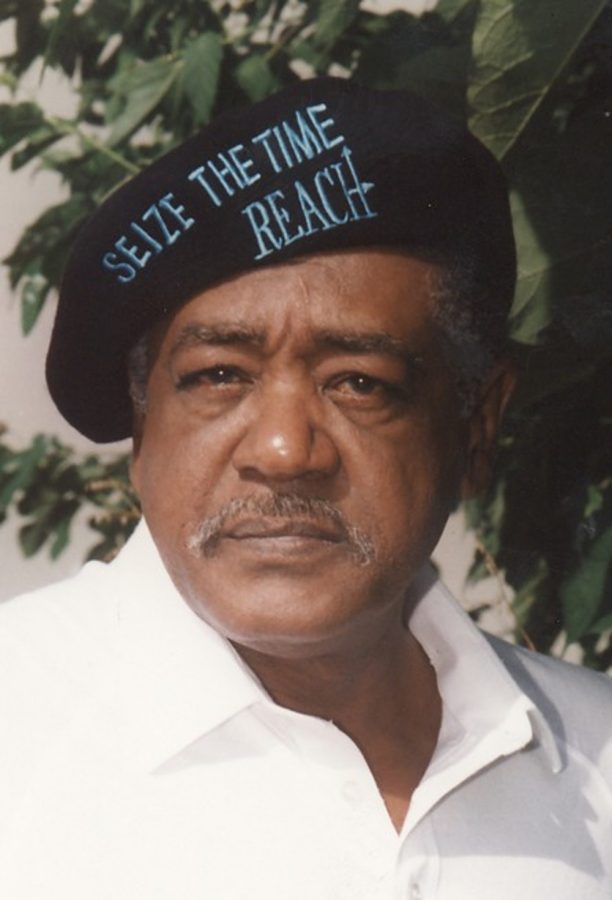

Bobby Seale, Black Panther Party co-founder discusses political activism

Bobby Seale, co-founder and chairman of the Black Panther Party, spoke with the American University community on Tuesday night about his experiences with black political activism. Student media had an opportunity to speak with him before the event.

Bobby Seale and Huey Newton founded the Black Panther Party, an African-American revolutionary party, in October 1966. Student journalists asked Bobby Seale about his decision to become politically involved and create the Black Panther Party.

Seale was not always interested in politics. In fact, Seale was an engineering major at Merritt College in Oakland, California. However, Seale said he was inspired by hearing Dr. Martin Luther King speak in Oakland, his home city, in 1963.

“Dr. King was talking about how no one, no organizations, no big corporations, whoever, they will not hire people of color,” Seale said. This helped form the basis of the Black Panther Party.

The Black Panther Party was developed in response to the lack of political power for black people and other people of color in the country, Seale said

“I did a demographic search across the United States of America,” Seale said. “This demographic search see[s] how many people of color [were] democratically elected to office. You know what I find? Fifty-five.”

Seale said how he wanted to expand political involvement and electoral seats for people of color to gain political power and economic equity for their communities.

“We need a political organization that gets more people elected to political office, the grassroots people,” Seale said.

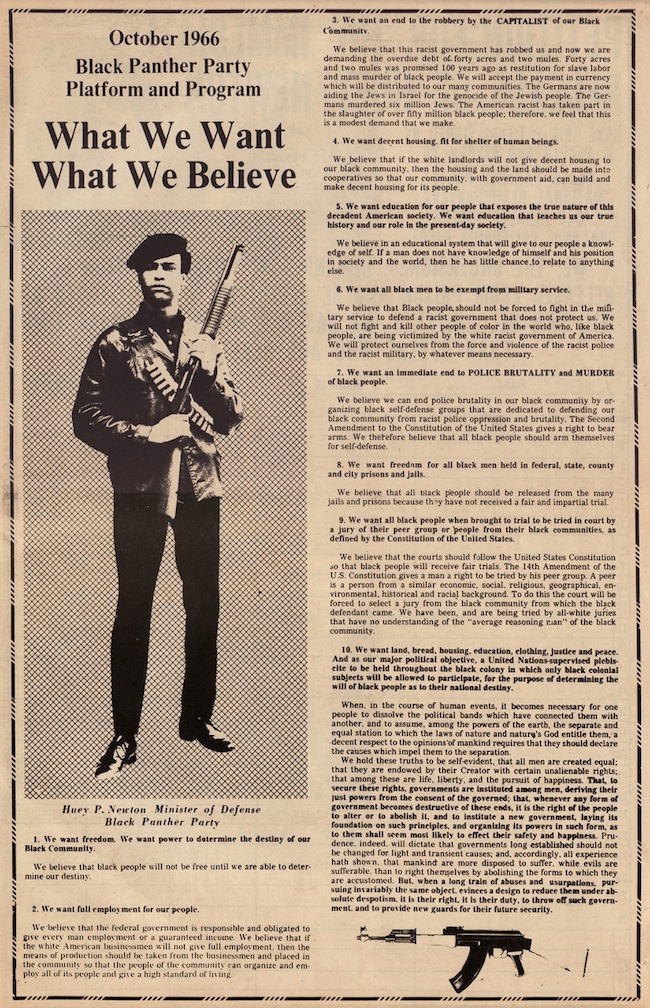

According to Seale, the Black Panther Party was based on a political and legal framework. The party is based on a Ten-Point Platform or Program, which was developed by Seale and fellow co-founder Huey Newton in October 1966.

They wrote this plan in the War on Poverty office, where Seale worked for the city government in Oakland County, California.

The Ten Point Program highlights different needs of the black community, including full employment, decent housing, inclusive and quality education, and all black men and women exempt from military service.

In summation, the Ten Point Program states, “We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace.”

The platform was developed based on components of the Declaration of Independence, Seale said.

“It is the right for the people to alter and change that government and provide new guardship for future security and happiness,” Seale said. “This was the operating concept and basis of that Ten Point Program and Platform.”

One significant act of the Black Panther Party leaders was patrolling their African-American communities with armed weapons to protect their residents from acts of police brutality. The overall goal of patrolling was to demonstrate their legal and civil rights to the police, Seale said.

“I made [Huey Newton] research every law related to guns before we went out patrolling,” Seale said.

This knowledge about their legal and civil rights became useful when facing arrest for patrolling the police, citing both California state law and the U.S. Constitution as proof of their rights.

“If you want to make the arrest, make the arrest. We’re not scared of the courtroom,” Seale said. “‘Cause when we get there, we’re gonna make a forum out of the courtroom about your racist, fascist butts.”

Patrolling was part of a wider effort to demonstrate the unjust power of the police and create a political machine, Seale said.

“We were trying to capture the imagination of people in the community,” Seale said. “The very fact that we did that spread around the community.”

The Black Panther Party also developed many community-based programs from their headquarters in Oakland California. These initiatives included tutoring programs, free children’s breakfast programs, and 13 established free health clinics, among others.

“The distortion is that we were a bunch of hooligan thugs,” Seale said, explaining how many people have viewed the Black Panther Party in a negative light.

Their Free Breakfast for Children Program alone served 200,000 children in 19 cities and 23 local chapters by the end of 1969.

Both the Nixon Administration and the Federal Bureau of Investigation under J. Edgar Hoover worked to eliminate the Black Panther Party during the 1960s, Seale said. J. Edgar Hoover referred to their political movement as one of the “greatest threats to American security,” including their Breakfast for Children program.

“The Nixon Administration, freshly elected, and the FBI structured operations to attack us,” Seale said. “They attacked more than 45 of my different officers.”

A month prior to his death, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. expressed that he wanted to work with the Black Panther Party and develop a “poor people’s march, dedicated to greater economic rights related to our civil rights,” Seale said.

The Black Panther Party membership grew exponentially after the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Seale said. Members of the black community, young people of color, and young white radicals all joined the movement. Membership over seven months increased from 400 members to 5000 members, with 49 chapters and branches across the country.

“They thought they were gonna stop the movement by killing Dr. King,” Seale said. “All they did was cause the Black Panther Party to explode across the United States of America.”

The Black Panther Party and Seale’s vision was to expand political empowerment to their community through grassroots outreach, Seale said.

“The increase in [the] amount of times you sell that Black Panther Party newspaper and of course, converse with brothers and sisters in [the] community, you are decreasing the apathy and increasing the consciousness,” Seale said about the messages he promoted to members of the party.

The legacy of the Black Panther Party continues to this day, and Bobby Seale continues to encourage people to become politically involved. This political movement and the need for political involvement for minority communities is still relevant now, Seale said.

“It’s still about that struggle–constitutional democratic civil human rights, involving bringing empowerment back to the hands of the people,” Seale said.

I'm a Senior majoring in Public Health. My areas of interest include health equity, housing access, and criminal justice reform. I have always been a writer...