Helter-Shelter: Motel living for D.C.’s homeless population

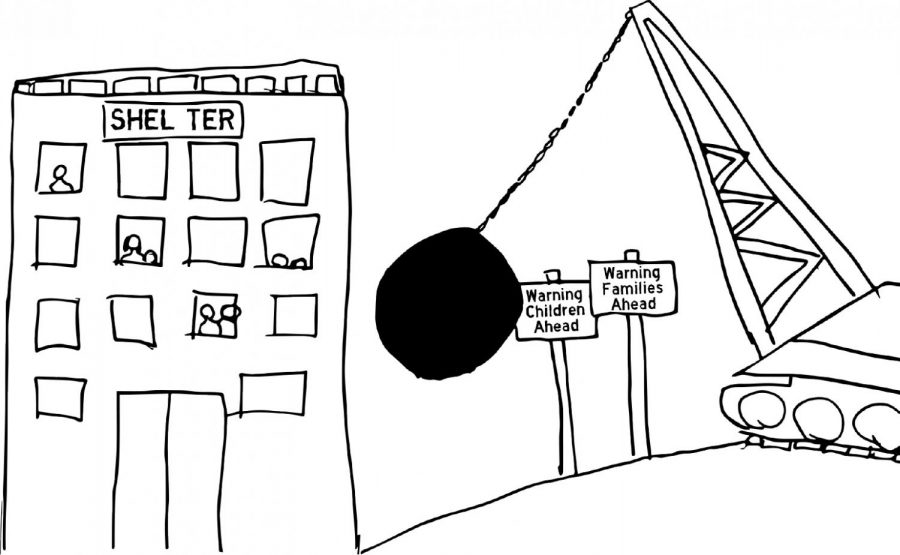

Art by Chloe K. Li

The last time 8-year-old Relisha Rudd was seen alive was March 2014. Rudd was living at District of Columbia General, a former hospital converted into a homeless family shelter, when Janitor Kahlil Tatum, posing as a doctor, kidnapped her. Authorities later found Tatum with a self-inflicted gunshot wound by the same gun that he used a few hours earlier to kill his wife. Rudd is still missing and family members and authorities speculate that she is dead.

The D.C. General Homeless Shelter is known for its notoriously bad conditions including infestations of rodents, cockroaches, mold, and several sexual assault allegations against the staff. One of Mayor Muriel Bowser’s campaign promises was to demolish the infamous D.C. General and replace it with six smaller homeless shelters.

Currently, only two shelters, The Kennedy Shelter in Ward 4 and The Horizon Shelter in Ward 7 are complete. D.C. General is expected to be closed by the end of the year, but on October 11, 34 families remained in the shelter while the city continued demolition on sight. Families will end up either in rapid re-housing or motels intended as temporary shelters.

Despite general agreement that D.C. General needs to be demolished, Mayor Bowser is under scrutiny from several homeless organizations like Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, Empower DC, Bread for the City, and Washington Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs, for starting demolition on building nine, an abandoned building beside the main shelter, with families still inside. Homeless advocates also argue that the city is pushing families out before replacement shelters are built, disregarding overcrowding in motels and setting families up for failure with rapid re-housing.

“The original commitment from the Mayor was not to close D.C. General down until

the replacement shelters were ready so that we could be sure there was enough capacity for all

the families in the system,” Amber Harding, a homeless advocate and attorney at The Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, said.

In August, seven D.C. Council members urged Bowser to postpone demolition after reports of high levels of lead 250 feet away from buildings with over 100 families inside. Instead of halting demolition, the city required weekly lead and asbestos testing.

“I feel like it’s been rushed personally because the land is sold to developers and the city is all about making money,” Ward 7 Advisory Neighborhood Commission candidate, Jewel Stroman, said.

“I don’t think there’s really too much concern over lead exposure. We have lukewarm babies at the shelter, we have infants, and all this demolition work going on. It shouldn’t be going on. There’s babies there. But when the cameras come around, everyone from Mayor Bowser on down will talk about how much they care about these families.”

Stroman associated the demolition with other potential incentives. “They want to hurry and tear the shelter down, get those people out of there, so they can build these multi-million dollar condos or whatever and it has a lot to do with gentrification. That’s just my personal feeling,” Stroman said.

She did not think D.C.’s low-income population stood to benefit from the move, either.

“I don’t know who [the land] is going to go to, but I know where it won’t go. It

won’t go to those families who need it. It will not go to the low-income residents of this city,”

Stroman said.

Families removed from D.C. General are currently living in motels or D.C’s rapid re-housing. According to a report by Washington Legal Clinic, D.C’s $31.6 million rapid re-housing program burdens low-income families and sets them up for failure.

“Except for Washington, no state relies more on rapid re-housing programs than the District, with rapid re-housing accounting for nearly one out of every five ‘beds’ in the homeless services system,” the report states.

The Clinic’s primary concern with the current system is that low-income families are expected to pay up to 40 percent of their income to housing and end up homeless when they can’t pay their rent.

“It’s a program that isn’t really set up to support people the way they need to be supported in this frontal market, and sometimes people end up worse off after they’ve been through the program because they end up in debt to landlords or evictions on their record,” said Attorney Amber Harding.

Many housing developments don’t fit families’ housing needs and they can’t afford the rent.

“However types of consumer debt, because they have to pay such a high portion of their income in rent. They sometimes have really bad conditions in the apartments, and then, at the end of that time period, they’re often facing eviction.”

Harding said that most of the families that were moved out of DC General are concerned about rapid re-housing and conditions in motels.

The DC Department of Human Services, started its rapid re-housing program in 2012 which is designed to help families find and stay in housing with rental assistance and case managers. The argument against the program is that families can’t increase their income fast enough to pay for the rent, especially in an expensive city like D.C, and end up homeless or suffer at the will of landlords who care very little about their residents.

“A lot of the rapid re-housing families, they get mistreated by these slumlords and DHS does not hold these landlords accountable at all,” Stroman said. “They do whatever they want to do and still get there money at the end of the month and these families meanwhile have to suffer.”

Another concern is the current condition of motels housing homeless families. The District started housing homeless families in motels in the 1980s. A report from the DC Fiscal Policy Institute found that the city spends 16 million dollars on motel rooms for temporary housing.

According to Stroman, who was formerly homeless in 2016, motels often have mold, flooding, and rodent problems. She recalled an infant next door to her dying from an asthma attack triggered by what the residents think was exposure to mice and rodents.

Additionally, Stroman said several families from the motels are not being provided food although motels are supposed to act as temporary shelters. She also said there were incidences of motel security personnel abusing their power.

She makes specific reference to a meeting in May where a woman reported that she had been raped by a guard at Days Inn. Two weeks later, the security officer arrested her on allegations of assault. The charge was dismissed after Stroman petitioned DHS and contacted the media, but DHS gave the woman a ten minute notice to vacate the Inn, said Stroman. After Stroman got in touch with the director of DHS, the victim was placed at the Holiday Inn.

“It’s my belief, and it’s her belief, that all of this happened because she spoke up at that meeting with the director,” Stroman said.

Although motels are supposed to act as temporary housing for families, the turnover rate of social-service caseworkers is so high that families have lengthy stays in motels that don’t meet their needs.

“We need the city to do something, besides just use these motels as permanent placement because that’s not what they were ever set up for,” Stroman said. “There’s no reason, I understand that DC may have a shortage of housing, but why are people in motels for eight, nine, 10, 12, 14, 18 months. That’s crazy.”

Stroman said the city has been denyings it’s using hotels as permanent placement. “That’s what they say when the cameras come around, but we know differently,” she said.

Resident Kelisha McDougald of Motel 6 on Georgia Ave. said, “That hotel was so awful and disgusting; it had so many mice and so many roaches, drugs, prostitution running rampant. The thing was it was still operating as a motel and a shelter.”

McDougald admitted she was no stranger to a mouse or two but that these conditions she was living under cause her anxiety to “go through the roof.”

“I had to stay up to guard my kids just to make sure no mice crawled in their belongings or in the bed with them. Or any of the other activities going on in the hotel got around them,” McDougald said. “It got to the point when I started sleeping in the lobby to catch workers and DHS as soon as they came in to tell them about the rodent situation. And I was laughed off, I was dismissed.”

According to families trying to move from temporary motels into voucher housing or rapid re-housing programs, including Stroman and McDougald, case managers are rarely helpful, and the turnover rate is so high that families feel they have no guidance or relationship with their caseworker.

McDougald said that because case manager turnover is so high, families rarely get adequate housing. According to the Virginia Department of Social Services, the turnover rate for family service specialists was 60 percent in their first year.

“They have case managers; we call them case manglers, they have social workers. But a lot of caseworkers are just overworked, their caseloads are too heavy, and the turn around rate is so crazy,” Stroman said. “A lot of these case workers get burnt out quick, and they can’t deal with it so they quit or they go to another agency. In the meantime we have families that are not getting the services they’re supposed to get.”

Overcrowding in motels is also a concern. As the motels accept more residents, resources are likely to be minimal. D.C. spends approximately $3,000 on motel housing per family a month and most families stay in motels for several months or even years.

“Since families stopped being placed in D.C. General, which was last May, we’ve seen the census for the hotels increase by quite a bit. So we are seeing more and more families getting placed in those hotels that are all out on New York Avenue,” Harding said.

Melanie S. Hatter from the Homeless Children’s Playtime Project said that the conditions in motel housing are not ideal for children involved in the program.

In 2009, The Children’s Playtime Project started a program at D.C. General for a safe place to interact and play including a toddler, intermediate, and teen program. In January of 2017, they started a new program at the Quality Inn Hotel on New York Avenue NE after leaving D.C. General. They have limited space, and when they asked the Quality Inn for more space and the use of their ballroom, they asked them to pay $1,000 per week.

Children are often forced to stay in a room and struggle to stay occupied at motels during the day. Hatter expressed the struggles for homeless children but acknowledged the dire conditions of D.C General and the necessity of its demolition.

“The issue with the hotels is that it’s what we call “pop up playtime,” Hatter said. “We don’t have our own dedicated playroom- we have to basically come in, pull out all the toys from storage, set everything up, and have the kids come in and play. When they’re done we have to break everything down and pack it all away. We’re making it work, but it limits the kind of programming we can do, the kinds of toys that we can bring in,” she said.

Despite criticism, Bowser’s first replacement shelter is a success with brand new interiors and an apartment building feel, and the number of homeless families dropped 19.4 percent. This year, Bowser’s administration secured $15.6 million for programs related to affordable housing.

The new budget also allocates “$10 million to increase the Home Purchase Assistance Program and Employer-Assisted Housing Program and $6.5 million for the Emergency Rental Assistance Program,” according to Street Sense.

Homeless advocates remain skeptical as Bowser pushes rapidly forward despite concerns of lead and discrepancies in her original plan for the closing of D.C General.

“These homeless families and these poor families do not have a seat at the table as far as when decisions are made, when laws are passed, and revelations are made,” Stroman said. “No one cares what these families have to say.”

Chloe K. Li (she/her/hers) is a junior studying journalism and transcultural studies. She reports as much for the people as possible and believes that...