A Silent Epidemic

Coping with Mental Health Illness in College

Kelly McNamara came to American University having never previously sought mental health services before. Walking into the Counseling Center for the first time, McNamara had a glorified view of what was going to happen.

“I don’t think it’s a bad place and I don’t want to lay judgment, but I had a graduate student who was running my sessions and she just wasn’t the best,” McNamara said while reflecting on her AU counseling experiences at her home in New Jersey. “I would come to her with these revelations of mine and she would say it wasn’t it. She was set on a specific thing saying ‘I think you have anxiety and I think that’s your problem’ rather than listening to what I was saying.”

For students with emotional trouble, the transition to college life can be challenging. From newfound freedom to the rigors of college-level coursework, the pressure and stress take its toll on students.

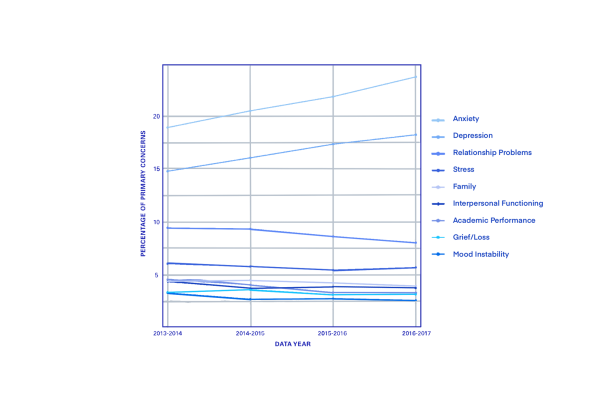

According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, nearly 80 percent of students do not receive mental health treatment. Similarly, the Center for Collegiate Mental Health 2015 Report found that demand for counseling services outpaced that of enrollment growth by as much as 500 percent.

In order to keep up with demand, the Counseling Center has shifted towards a “menu of options for students” and a campus-wide approach to mental health.

These offerings include services that go beyond the Counseling Center, such as AU’s RecFit, Peer Wellness, and other health-related programs. Horne suggests training seminars with faculty and students to arm them with the education that they need to notice precursors of stresses of students so they can intervene when necessary.

“It’s kind of hard because [the counseling center is] there for short-term health,” McNamara said. “They’re supposed to refer you somewhere else for long-term because it’s not supposed to be a long-term therapist. So part of me thinks what they’re doing is fine. But one thing they’re not appropriate for is diagnosing. That’s not their role and they shouldn’t put you in a labeled box.”

****

In 2014, the AU Counseling Center reported a 40 percent increase in the number of individuals they served. Campus resources have since been strained in attempts to deal with the rising student demand for mental health services. According to a 2013 survey conducted at the AU Counseling Center, 91 percent of respondents reported feeling “so stressed they couldn’t function.”

“Universities across the country are seeing an increase in services and there are recommendations of how many clinicians a university should have but it’s about one per 1,000 students I believe,” said Shatina D. Williams, assistant director for Outreach and Consultation. “So AU does keep with that and it’s not an anomaly in relation to other universities.”

As of a few years ago, the campus began a revival of the wellness center, which offers information, workshops and programs to help students learn to manage stress and live a more healthier lifestyle.

Individual therapy is time-limited at AU’s Counseling Center, meaning only six to eight sessions with a clinician are permitted.

“Six to eight sessions allows us to meet with students who are wanting services,” Williams said. “If we didn’t put a cap on services, a large contingency of students would never be seen or know what therapy is. It allows, hopefully, everyone who wants to seek services to have them.”

AU’s Counseling Center walk-in hours remain a window between 2-4 p.m. every weekday.

In addition to the support offered at AU’s Counseling Center, the Academic Support and Access Center (ASAC) provides services specifically for students with disabilities, including learning disabilities, Attention Deficit Disorder, and other physical and psychological disabilities.

“There is an overlap between ASAC and [AU’s Counseling Center],” Williams said. “If a student is struggling with schoolwork and needs certain accommodations for them, they go to ASAC. Here [at the Counseling Center], we focus on social and emotional functioning whereas they focus on academic performance and accommodation.”

No level of government has created a legal mandate demanding that schools provide mental health services according to The Jed Foundation. Still, there can be a financial benefit to universities that spend money on these services.

“[The university] wants to keep its tuitions without issues of liability, but it comes to the point where we have to decide if we’re going to be transparent and just take the risk for the students,” said Dr. Amanda Berry, a professor of literature.

Healthier students continue to higher retention rates and graduation rates, leading universities across the country to recognize that academics and mental health are deeply intertwined and have taken the approach of integrating the two more clearly.

These universities stand a better chance of retaining students struggling with mental health, while also keeping tuition, according to Berry. That said, there’s a big difference between having mental health services and actually getting students to use them.

Students are allowed to take a temporary medical leave, but according to the AU website, “Students should consult with their academic advisor to discuss all options.” At the same time, students can request accommodations such as allowing more frequent excused absences. Having note takers and extended testing periods are also options provided by the university.

“Technically, students can’t fail just by being absent but if they miss three or five classes, they start to tank and it gets very hazy,” Berry said. “Students appeal grades and I get it, college is expensive. Instead of colleges treating students like consumers, having a label of what is a ‘legitimate’ excuse without diminishing those with anxiety or depression all because John Smith has a hangnail.”

****

Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric problems among college students. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in five students living in the U.S. has symptoms of a mental health disorder.

“My mental health came in waves, the first during my freshman year and then this last year,” McNamara said.

As a senior, McNamara is finishing her undergraduate career through courses at a local university in New Jersey while on medical leave status with AU.

While most of her professors were accommodating, she recounted a particular experience with a professor whose class in which she was already doing poorly.

“I was explaining I had personal issue but she told me I had to tell her exactly what was going on. So I mumbled ‘eating disorder’ under my breath and she said, ‘What does that have to do with math?’,” McNamara said.

From teaching general education courses for the literature department, Berry has encountered a range of people who have struggled with mental illness.

“It’s never about the legitimacy of the event or problems a student is facing but sometimes faculty members are being asked to help students in ways that we aren’t equipped to because I am not trained as a therapist,” Berry said.

Students have struggled with explaining to their professors and administrators that even though their grades are okay, their mental health might not be.

“I didn’t go to [counseling] when I probably should have,” McNamara said. “I ended up in the hospital a few times. The first three times I didn’t go to the Dean of Students because I just winged it and told my professors. The last time, I reached out because I really did want to do well in my classes. It was helpful to have the letter sent out by the dean.”

The culture of selling colleges as “away-parents” for students makes it more difficult for the students themselves to use counseling services without feeling belittled or too dependent.

“How can colleges, parents, and hospitals articulate what students should do?” Berry said. “You’re a grown-up and live on your own but still live under an institution to take care of you? It’s hard to figure out what you need to do with that.”

McNamara said that AU’s culture has been repeatedly criticised for being too competitive and cut-throat.

“I feel like everyone, especially with social media, will post on Facebook at the end of the semester, their GPA, how many internships they had, how many jobs they had and this long list of things they want to share,” McNamara said. “There were semesters where I would compare myself to the AU culture and I was falling behind. That took a toll on my depression, anxiety, and mental health cycle.”

When alumna Laura Yochelson came to campus without the traditional worries about the “freshman 15”. She had been diagnosed with anorexia nervosa at age 13 and, after a recovery, relapsed at age 15.

By the time she started college, she was again in recovery but said she didn’t really think about the food in choosing her college. She had received a scholarship and placement in an honors program at AU, so that’s where she ended up. But, she found life on campus challenging. The campus culture, she felt, was all about fitting in — and that included some peer pressure to eat more, and not necessarily healthful, food.

“There was pressure to fit in, live a typical college life, eat typical college food,” Yochelson said. “I just didn’t feel supported.”

Yochelson moved back home to Bethesda, after her first semester at AU and managed to work through her recovery before graduation. It would have been “really cool,” Yochelson says if she could have been open about her condition and found a support group to help.

Since McNamara’s medical leave, she has had a chance to experience campus cultures outside of AU.

“[Other schools] just don’t have this perfectionistic, do-everything kind of attitude,” McNamara said.

While AU encourages students to be busy with school, internships and extracurricular activities, this doesn’t work for everyone. Some students who come to AU with a pre-diagnosed mental health disorder can juggle a busy schedule while others are more vulnerable.

“Sometimes it’s just a matter of asking [for help],” Berry said. “But that can be hard for a freshman making the transition from high school to college.”