Taking the Initiative

Transforming the Way AU Perceives Mental Health

When Brian Fu began his first semester at American University in the fall of 2017, he soon found his mental health declining. After searching for a student organization that was tackling issues of mental health among college students, and finding none, he and three other students decided to form Mental Health Initiative (MHI), which became an official student organization in February 2018.

Increased rates of counseling center appointments are outpacing college enrollment by a factor of more than 7 to 1.

AU’s Counseling Center is overburdened as well. First-year students Simrnjit Seerha and Samantha McAllister received individual counseling appointments approximately six weeks after requesting services from the center. After six sessions with an on-campus counselor, they will have to find an off-campus private therapist or psychiatrist.

As MHI was in the process of becoming an official student organization, some of its members spoke with Dr. Traci Callandrillo, the Counseling Center’s executive director, and voiced students’ concerns over its policies. Fu specifically mentioned the six-visit limit and Lilli Specter, MHI’s communications director, wanted students to have access to counseling on the weekends.

Callandrillo was aware of the complaints and explained that they were doing the best they could with their given budget.

“Their response was interesting,” Fu said. “They would like to do more, but they can’t because of the resources they are given.”

From Fu’s perspective, the Counseling Center cannot be expected to attend to the mental well-being of every student. Some students arrive on campus with a diagnosed mental illness and likely need a psychiatric consultation to receive prescribed medications.

“One in four college students has a mental illness,” Fu said. “That alone would be a monumental task for the Counseling Center to try to take on: not only the general mental health of those people but their diagnosed mental illnesses.”

Students and nonprofits are working to combat the flood of students seeking help. Active Minds, a nonprofit centered in the District, works with college students to form on-campus organizations to raise awareness of mental illness and encourage self-care among students. Laura Horne, director of programs at Active Minds, says that counseling centers will never be able to satisfy every student’s needs with individual counseling.

“From our side, we feel like it’s important to continue to increase the capacity of the Counseling Center and its services,” Horne said. “At the same time, we may never be able to keep up with this demand in the Counseling Center alone.”

Horne and the students at MHI believe the community needs to have a better understanding of mental health so that students are more willing to discuss it with their peers. Hopefully, fewer students will need to go directly to a counseling center to have their first conversation about mental health.

“It’s really going to be important that we take a prevention approach that involves everyone,” Horne said. “Ideally, everyone in the community is trained on how to notice signs that a student is in distress and what to do about that. These demands are not going to be met by the Counseling Center alone. It has to be the entire community.”

In order to reshape communities to support students with mental illness, the underlying cultural issues need to be understood, according to Jean Twenge, a professor of psychology at San Diego State University. Twenge has researched the lifestyles of a generation she has labeled “iGen.”

“[iGen are] born between 1995 and 2012, members of this generation are growing up with smartphones, have an Instagram account before they start high school and do not remember a time before the internet,” Twenge wrote in an article in The Atlantic.

Twenge links social media use to an increase in depressive symptoms and finds a correlation between screen time and feelings of loneliness. Members of iGen are also less likely to leave the house without their parents, drive a car, consume alcohol, go on a date or have sex than previous generations.

Specter has read and agrees with Twenge’s research.

“We’re so worried about what other people think on social media,” Specter said.

Horne is hesitant to scapegoat smartphones as the only source of current issues in mental health.

“I think that we’re all looking for something that we can point to because if we knew what it was we could just focus all our energy on that,” Horne said.

Fu wants to center on the stigmas surrounding mental health at AU, which are hindering students from practicing proper self-care.

One such stigma comes in the form of students’ general ignorance of mental illness.

“There are a lot of labels. I’m bipolar, and that and schizophrenia are really labeled as being dangerous when they’re really just misunderstood,” Fu said. “When you have something like anxiety or depression, it can be very easy to imagine someone huddled in a corner, unable to participate in society.”

Another stigma is that mental illness is imagined or an expression of selfishness and narcissism.

“We wouldn’t call it selfish to eat healthy food or to go exercise because you’re doing it for yourself,” Fu said. “We wouldn’t call those things on their own selfish, but when you call it mental health, it’s selfish.”

These stigmas have a way of delegitimizing mental illness and discouraging people from talking about it. Fu wants mental illness out in the open so that students are more prepared to confront it.

“Society needs to get to the point where colleges are the starting point for where you learn how to take care of yourself,” he said.

It’s possible that stigmas are contributing to the overburdening of the Counseling Center, according to Horne. More students using mental health services should be a sign that they recognize the importance of caring for their mental well-being, but some of these illnesses cannot be addressed by the Counseling Center’s clinicians.

“If you needed to get a surgery, you wouldn’t question it,” Horne said. “We just get what we need, no matter how much it costs. I think this goes back to… this idea that mental health is different and rather than paying for it, I’m just going to handle it in other ways.”

This stigma is reflected in public policy. Before the passing of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act in 2008, physical health was prioritized over mental health in insurance plans. The Affordable Care Act in 2010 required insurance companies to pay for depression screenings.

The policies may not have led to considerable change. According to the Mental Health Treatment and Research Institute, as of 2017, 63 percent of behavioral healthcare visits were out-of-network in the District. Behavioral healthcare refers to mental health and substance abuse services.

For MHI, much work needs to be done outside the realm of policy. They may not be able to resolve the overburdening of the Counseling Center’s resources, but they can transform the way the AU community perceives mental health.

An important step in starting positive conversations about mental health is encouraging students to practice taking care of their well-being.

“[MHI can teach students] to keep yourself in the moment, to try your best not to stress and get too anxious about what is coming in the future, but to keep your mind here, now,” Fu said.

Fu hopes to organize community events such as movie screenings and monologues where students can share stories about their experiences with mental illness. He emphasized collaborations with other student organizations, specifically multicultural organizations.

“Everyone has mental health and everyone needs to maintain it, whether they know it or not,” Fu said. “Being one of those ultimate intersections, we have kind of unlimited potential to talk about a lot of different things.”

There is data on the mental health of college students, but AU lacks consistent measurements.

First-year student Sarem Haq is working to collect data on the student body’s overall mental well-being. As a senator for the Campus-at-Large in AU Student Government, he passed a bill in December 2017 to establish a monthly mental health survey of the student body.

While campaigning, Haq reached out to Fu to talk about mental health after he noticed it was a hot-button issue on campus. After Haq was elected, he decided to prioritize mental health legislation.

“I think the first step to being able to legislate on mental health is understanding what issues people are facing and what they think student government should be doing for them,” Haq said. “Acting on information rather than rhetoric is crucial. Not just in mental health but in any policy that we try to advocate for.”

The Counseling Center has a mental health survey, but according to Haq, the response rate is low and the results are unavailable to students. If AUSG wants to change the way mental health is handled on campus, they need to know what is worth changing.

After the data is collected, Haq hopes to develop a strategic plan for addressing students’ grievances with mental health services on-campus. He wants mental health to remain a focus of AUSG after he leaves office.

For now, Fu wants to emphasize how the student body can help each other.

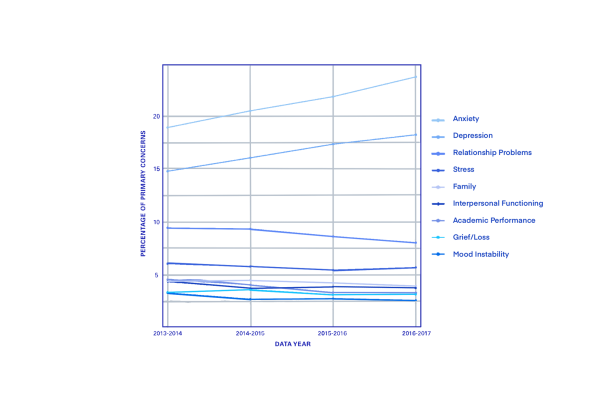

“We have to turn cold hard facts of ‘statistically there’s more depression [and] anxiety’ into common understanding, compassionate, just, humanness,” Fu said. “The understanding that people struggle and it’s OK.”