The Legacy of Language

The role of language in the formation of the Latinx identity

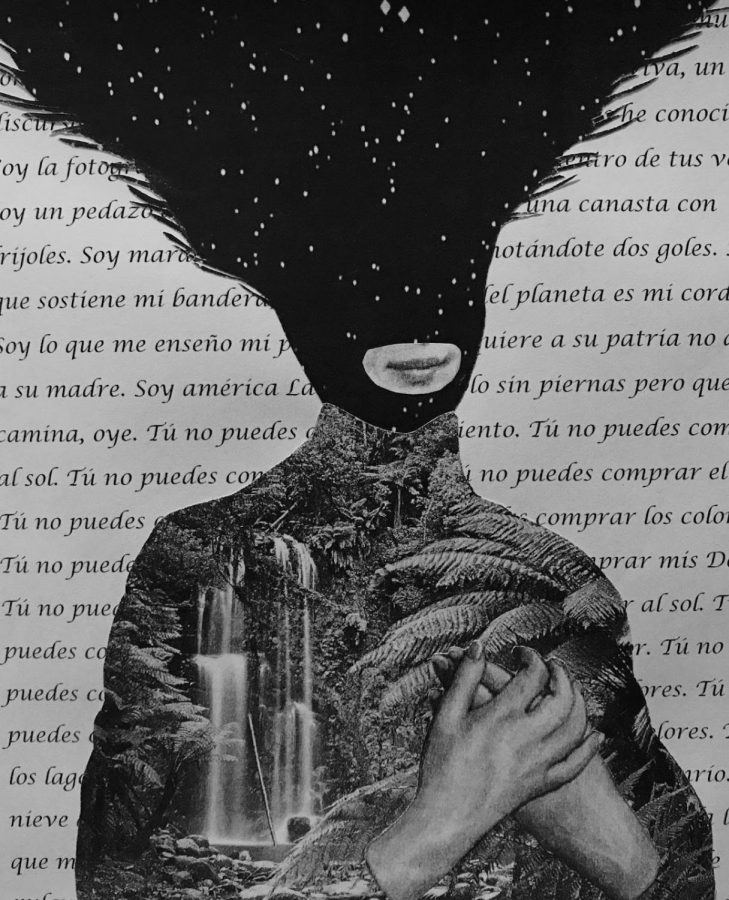

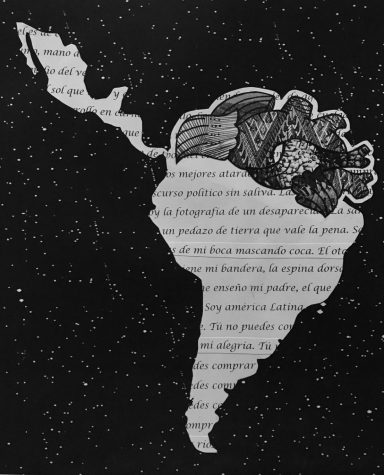

Art by Katia Rasch

The Latinx identity is just as complex as Latinxs are themselves. There is no exact culture that defines them. There are 26 countries in Latin America, each with its own dialect, music, national sport, and with many other unique features. It’s difficult to pinpoint an exact Latinx way of life.

Recently, it seems that ‘immigrant’ is becoming a common addition to the Latinx identity that makes it increasingly interesting to study. What makes one more Latinx? What does it take to revoke your “Latinx card”, metaphorically speaking? How is the connection with heritage affected by being raised in the United States when it comes to Latinxs and their descendants? And perhaps more importantly, what is the significance of language when it comes to the connection and the pride of culture and heritage?

According to a 2015 report from the Pew Research Center, Hispanics in the United States break down into three groups when it comes to their use of language: 36 percent are bilingual, 25 percent mainly use English and 38 percent mainly use Spanish. Among those who speak English, 59 percent are bilingual. In other words, there is no “right” or “wrong” level of language proficiency. However, it is important to look at how the different levels of proficiency correlate with identity and connection with culture.

A series of interviews from Latinxs show that those who are proficient in Spanish and/or Portuguese insist on language being one of the most — if not the absolute most — important factors when it comes to the Latinx identity in the U.S..

Those who aren’t as fluent, or do not speak the language at all, tend not to see language as such an important factor, and still feel very connected with their own culture despite lack of fluency.

Most Latino adults say it is not necessary to speak Spanish to be considered Latino. According to a recent Pew Research Center survey of Latinx people, 71 percent of Latinx adults hold that view while 28 percent say the opposite. When it comes to non-Spanish speaking Latinx people, such as Brazilians, they tend not identify as Latinx, due to the lack of acceptance by Latinx people from Spanish-speaking countries.

—

Chia-Ry Chang Ureña, a junior in the Kogod School of Business, was born in Costa Rica and grew up in San Francisco. Her father is Taiwanese, so she speaks Mandarin as well as Spanish. She considers herself to be both Asian and Latina.

To her, identifying as equally Asian and Latina does not deter her from feeling any less of either.

“Speaking the languages [of your culture] connect you in a way that not speaking it can’t, because you can submerge yourself without roadblock,” Chang said. “Not speaking the language can make you feel left out, because you miss tidbits that characterize people from that country.”

This demonstrates the widespread belief that many Spanish speaking Latinx people hold — that lack of proficiency in language causes a disconnect from culture.

—

Despite the increase of the Latinx population in the United States, the Spanish language is getting lost through the generations. According to Census Bureau projections, the share of Hispanics who speak only English at home will rise from 26 percent in 2013 to 34 percent in 2020. Over this time period, the share who speak Spanish at home will decrease from 73 percent to 66 percent.

However, many Latinxs of the later generations are beginning to feel as if Spanish shouldn’t be pushed to the side as English becomes the language of focus for immigrants. A 2011 survey conducted by the Pew Hispanic Center, which found that nearly all (95 percent) Hispanic adults believe it is important for future generations of Hispanics in the U.S. to be able to speak Spanish.

An example of such is sophomore Matthew Matos. He was raised in Mahwah, New Jersey but considers himself to be both Puerto Rican and American, since he has Puerto Rican heritage from both sides of his family. His parents chose not to focus on teaching him Spanish because they lived in a predominantly white suburban town, and thought speaking Spanish would hold him back.

This is not an uncommon situation. A 2009 report from the Pew Research Center shows that 22 percent of young Latinos (ages 16-25) say their parents often encouraged them to speak only English, compared with more than a third of older Latinos (ages 26+) who say the same.

Now, Matos is now at an advanced level of Spanish from taking Spanish classes throughout high school and college.

“Being Puerto Rican brings the responsibility of speaking Spanish. It is a big part of the culture,” Matos said.

—

Some Americans of Latinx heritage do not see language as the decisive mark in whether or not a Latinx is actually a Latinx.

Savina Tapia, a sophomore in the School of Public Affairs, was born and raised in Boston, with a Chinese mother and Dominican father.

“Not being fluent in Spanish made me feel left out, especially with my dad’s side of the family because they all speak Spanish,” Tapia said. “I feel ashamed in public when people ask me [about speaking Spanish] because I don’t know Spanish.”

Additionally, being half Asian and half Latina means many people demand that she choose a heritage of preference; whether she identifies as Chinese or Dominican.

“I accept the fact that I fall between two cultures and I can’t anchor myself in either,” Tapia said about her two identities. “I know that I will always be both and no one can take that from me.” This confidence in her self-identity is what allows her to still feel Latina without feeling the imperative need to learn Spanish.

“But it would make certain things a lot easier,” Tapia said. “I feel a disconnection and left out, but I still don’t think language proficiency is extremely important when it comes to being connected to culture.”

—

A perspective that brings new insight to the matter is that of Latinx international students.

Sophomore Alberto Gomez was born in Spain and grew up in Bogotá, Colombia. To him, any American of Latinx heritage is American, but he feels like he can relate and connect more with them if they are able to speak fluent Spanish to him.

“First and most importantly, they need to speak the language,” Gomez said in regards to the qualities necessary for a Latinx American to have in order for him to feel as if they shared a culture.

“Secondly, they need to understand and know the culture from where they originate. Latin culture is based on family. Family is the most important thing in life. They must have a strong connection with their family.”

Gomez shared that when interacting with the Latinx Americans on campus, many times they say they are Latinx but would not speak Spanish to him. Gomez believes that many Latinx parents choose to not teach their children how to speak Spanish when they arrive to the U.S. because they think Spanish is an inferior language and will be looked down upon by the rest of society.

However, according to Pew Research Center, 95 percent of adult Hispanics believe it is very important or somewhat important for future generations of U.S. Hispanics to speak Spanish.

—

Another factor to consider when it comes to figuring out the Latinx identity are the non-Spanish speaking Latinxs. Brazilians, who are not considered to be “real” Latinxs by many Spanish speakers, face even more difficulties accepting their identity when it comes to being a Brazilian American.

Junior Natasha Bonilha is one such person. She was born in Vernon, Connecticut and spent half of her childhood in Connecticut and the other half in Shanghai. She is fluent in both Spanish and Portuguese.

Bonilha only recently began to consider herself Latina.

“A lot of Brazilians don’t consider themselves to be Latinos. My parents never considered themselves Latino; they considered themselves to be Brazilian. I think that in Brazil, a big idea that people still can’t seem to separate themselves from is that being Latino is different than being Hispanic.”

It is important to note that by definition, Brazilians are Latinx. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines ‘Latino’ as either “a native or inhabitant of Latin America” or “a person of Latin American origin living in the U.S.”

The term ‘Hispanic’ refers to people who speak Spanish as a native language. Therefore, a Spaniard would be considered Hispanic, but not Latinx.

Among Hispanics themselves, many are ambivalent about the two terms. According to a Pew Research Center survey of Hispanic adults, 50 percent say they have no preference for either Latino or Hispanic. But among those who do have a preference, Hispanic is preferred over Latino by a ratio of about 2-1.

Although Bonilha believes speaking Spanish isn’t important for one to feel Latinx, it is key for understanding the culture.

“I cannot stress its importance enough, especially with languages that are built with the culture,” Bonilha said. “By that, I mean that there are some languages that you can figure out different cultural ideals and facts by listening to expressions and colloquialisms.”

—

To focus on a singular pre-conceived idea of what the typical Latinx is supposed to look like is to entirely miss the kaleidoscope of people with different cultures, backgrounds, beliefs, and values. To invalidate a Latinx for only speaking English is to erase their entire cultural and familial history. Every Latinx will express their identity in distinct and valid ways, because there isn’t one way to be Latinx. The Latinx identity is as complex, rich, and beautiful as Latin America itself.

Camila Cisneros is a sophomore studying international relations and communications.