Why Us? The alt-right’s assault on American University

A litany of hateful acts mar AU’s recent history

Art by Hannah Tiner

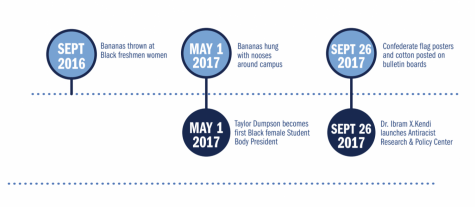

On Tuesday, Sept. 26, American University opened another chapter in its sordid history of racist acts on campus with the school’s second high-profile racially motivated incident on campus since May.

That evening, circulating first on Twitter, then on Facebook, were photos of cotton stalks taped to printouts of the Confederate flag.

They were scattered across campus, pinned to bulletin boards in Battelle, McKinley and Mary Graydon Center. Most notably, one was hung on a board advertising the new Anti-Racist Research and Policy Center in Battelle.

It was the night of the debut of Professor Ibram X. Kendi’s Anti-Racist Research and Policy Center. Kendi is celebrated for his 2016 book “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America”, which won a National Book Award and is a high-profile new addition to AU’s faculty.

In an interview with AWOL, Kendi was unsurprised that he had been targeted.

“In studying the history of racism,” Kendi said, “I know that one form of racism is racist violence or terrorism that typically pounces when some sort of progress is being made.”

While Kendi and other community leaders were not expecting September’s racist acts, they came as no shock.

“I was tired, I wasn’t very surprised by it,” said Devontae Torriente, a senior studying Justice and Law, and the former president of Student Government (AUSG). “I think if you’ve been paying attention to the world […] or recent events at AU, or the history of the black student community at AU, it’s not very surprising.”

September’s racist acts, in their timing, location and content fit the bill for what seems like a trend of white nationalist, or “alt-right,” attacks on AU and other universities across the country. In post-2016 America, liberal schools like AU are becoming targets for the vitriol of alt-right and falling prey to their tactics.

In a statement made to the campus community published Sept. 27, AUSG President Taylor Dumpson reassured the AU community that AUSG would not stop advocating for a more inclusive, united, and safe community.

“The significance of this occurring as our country continues to struggle with its history of white supremacy also cannot be ignored,” Dumpson said.

A History of Hate

The Confederate flags were the third highly publicized racially motivated incident in just as many semesters at AU.

According to the 2017 American University Annual Security Report, there were six recorded hate crimes on campus in 2016. In 2015, there were three recorded crimes, and in 2014 there were 6 recorded crimes.

Public Safety defines hate crimes as a criminal offense that “manifests evidence that the victim was intentionally selected because of the perpetrator’s bias against the victim.”

The crimes in the report ranged from vandalism offenses, assault, intimidation and burglary. They were related to racial bias, religious bias, ethnicity bias or gender bias.

In May, the U.S. Attorney’s Office, in connection with the FBI, Metropolitan Police, and American University Campus Police (AUPD), opened up a hate crime investigation after an unknown person came onto campus and hung bananas in nooses from trees outside of the Mary Graydon Center, the East Quad Building, and outside of a shuttle stop. The incident occurred the day after Dumpson, AU’s first Black female AUSG president, was sworn into office.

The noosed bananas were labeled with “AKA FREE,” a reference to Alpha Kappa Alpha, the historically Black sorority at which Dumpson is a sister.

At the time of print, law enforcement officials have yet to identify the suspect.

At the same time, Dumpson was harassed by Andrew Anglin, the editor of The Daily Stormer, a KKK-affiliated white nationalist website. Anglin encouraged his readers to “troll” Dumpson after her election, according to BuzzFeed.

The Daily Stormer and Andrew Anglin could not be reached for comment. Their website is now being hosted on the Deep Web following their involvement in August’s “Unite the Right Rally” in Charlottesville, Virginia.

On May 1, just hours after the banana incident, Dumpson released her first statement as AUSG President reflecting on the attack.

“It is disheartening and immensely frustrating that we are still dealing with this issue after recent conversations, dialogues, and town halls surrounding race relations on campus,” Dumpson said. “But this is exactly why we need to do more than just have conversations but move in a direction towards more tangible solutions to prevent incidents like these from occurring in the future.”

In the same statement, Dumpson implored the community to stay strong.

“As the first black woman AUSG president, I implore all of us to unite in solidarity with those impacted by this situation,” Dumpson said. “We must use this time to reflect on what we value as a community and we must show those in the community that bigotry, hate, and racism cannot and will not be tolerated.”

Responding to Hate

In a campus town-hall meeting following the attack in September, newly appointed AU President Sylvia Burwell delivered an emotional statement in which she said, “An attack on one of us is an attack on all of us.”

In an open letter addressed to campus, Rev. Mark A. Schaefer, university chaplain, “condemn[ed] these acts as violating not only our deepest values, but also the recognition that every person is a child of God and worthy of human dignity.”

Until recently, AU had not regularly made national news for racism. American is widely regarded as a bastion of liberal activism.

Princeton Review, a popular college ranking organization, named AU the fourth “most politically active” university in the United States and in its review wrote that “liberals run the show” on campus. Despite the relative lack of national coverage, in the town-hall and on social media, many students say racism runs deep on campus.

“I think there was a culture [on campus] that was conducive to that act,” Torriente said. “We build a culture where we don’t address the issue of white supremacy and antiblackness head on.”

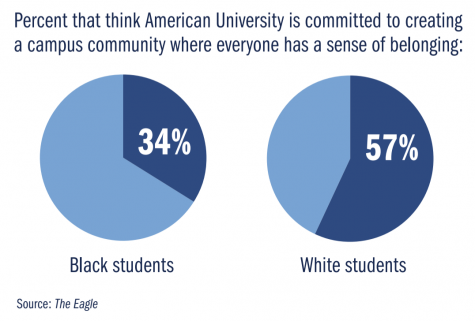

A campus climate survey released by the AU administration in October found only 34 percent of black students believed that the university was committed to “creating a campus community where everyone has a sense of belonging.” Comparatively, 57 percent of white students answered ‘yes’ to the same question.

Student groups, including the Black Student Union, AU NAACP, and The Darkening (although not an officially recognized student organization) released a set of demands following the first racist act of the 2016-17 school year.

Among their demands were the “actual implementation” of programs to train AU staff to respond to oppressive behavior, the formation of a “campus task force” composed of students for investigating racially-motivated crimes, and the establishment of separate resource centers for students of color and other marginalized groups.

AUSG also released a set of action steps after the flags were hung around campus. These actions were broken down into four categories: safety, retention, education and accountability.

Some of the actions requested included more transparency between AUPD and the AU community, and the hiring of staff that focuses on the retention of students of color and other minority students on a more grassroots level. AUSG also called for the creation of “cultural competency” training for students, staff and faculty, as well as increased transparency and accessibility to the university’s budgets and investments.

Students organized a protest in front of MGC in the days following September’s racist acts. Kendi spoke to the crowd, offering a message of strength and solidarity with AU’s Black students.

Given these developments, many students found themselves asking themselves whether or not AU was really playing host to white nationalists and alt-righters.

“I think a lot of people were disgusted, and also very confused as to how we could let someone who was not a member of the community physically come onto campus and do this,” Torriente said.

Facing a different threat

Following September’s racist acts, campus police launched an investigation into the potential culprit. The office released security footage that depicted Public Safety’s prime suspect.

The man appeared to be around 40 years old, wore a reflective vest and a hard hat, and carried a toolbox. He didn’t look like a student. His appearance suggested that he was a contracted worker and likely came from off-campus.

At the time this story went to press, city and campus police have yet to identify the suspect.

The idea that someone from off-campus was responsible for September’s racist act doesn’t sound like a particularly relevant detail––if it weren’t for the fact that it’s part of a trend.

After the incidents of last May, campus police released surveillance footage of their prime suspect that captured a car pulling onto campus, offloading a hoodie-clad man, and driving off. It seems that even before the events of this semester, non-students were already involved in committing acts of hate at AU.

As The Blackprint reported in September, the reverse sides of the Confederate flag posters featured the logo of the “D.C. Counter Resistance.” Their logo is two overlapping white circles on a black background and has ties to Milice française, an anti-Semitic group formed during World War II.

This group has reportedly been operating in Ward 4, the northernmost part of the city. An August article in DCist references anti-immigrant posters appearing on buildings and telephone poles around the neighborhood. The group is part of the alt-right movement—pointing to the connection between racist acts on AU’s campus and the greater rash of alt-right “social regressivism.”

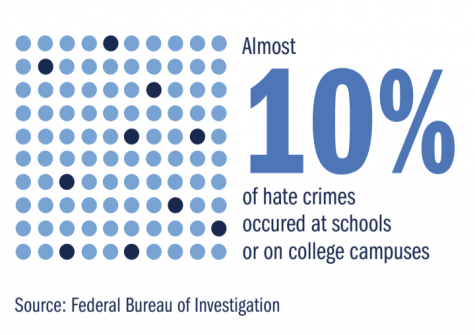

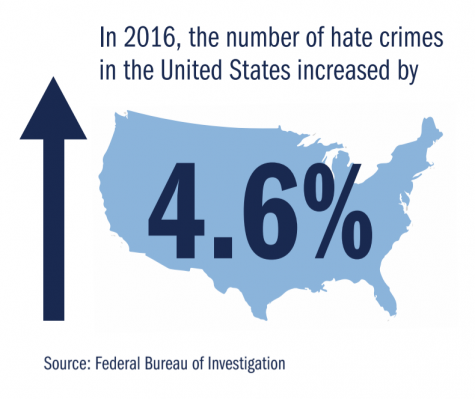

The number of hate crimes in America increased by 4.6 percent in 2016, according to a report released by the FBI. The statistics indicated that almost 10 percent of hate crimes occurred at schools or on college campuses.

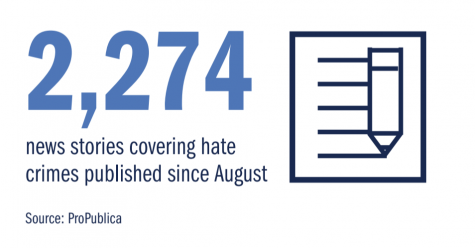

ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom, has been actively tracking hate crimes as a part of its Documenting Hate research project.

“This is a definite pattern that we’re seeing,” said Rachel Glickhouse, the partner manager on the Documenting Hate project. “It’s happening all over the country.”

According to ProPublica’s public GNews index database, in partnership with Google, bias incidents spiked following the 2016 election. At the time this story went to print, 2,274 news stories covering new or developing hate crimes have been published since the first week of August alone. The crimes range from vandalism to racially-motivated assault. Many took place on college campuses.

Glickhouse explained in general terms that the spike in campus hate crimes is a result of the emboldening of preexisting white nationalist elements. White nationalists feel freer to voice their hateful ideology in the current political climate. But why then has AU been so aggressively targeted?

“It’s not just trolling for trolling’s sake,” she said of groups like DC Counter Resistance. “They’re also trying to recruit in many cases.”

Why Us?

Lecia Brooks, Director of Outreach at the Southern Policy Law Center (SPLC), cited AU’s history of enacting positive social change as one of the driving factors behind its recent outbreak of vandalism. She says that AU was one of few schools in the country to follow through on improving its level of inclusivity in the wake of racist incidents on campus.

“AU has done a lot and continues to do a lot, to address these issues,” Brooks said. “I think the administration stood up last school year to this hate … [and] got a lot of media attention, got the attention of members of Congress.”

She says the Anti-Racism Policy Center is another example of AU taking the initiative to counter attacks by white nationalist groups. Brooks says the response to hate on other campuses is much more watered-down and usually consists of a college president denouncing the incident but not following up with action.

AU, in her opinion, is more involved than that. The progressive mentality, Brooks says, is an important root cause of the alt-right’s assault on AU.

“What [AU is] doing to address these issues is one of the reasons that you’ve come under attack,” Brooks said.

Torriente echoed that point.

“I think that the AU community is imperfect and that there’s improvements to be made, but I think that we are a much more progressive school than most other schools, and I think that’s what we’re known for being,” Torriente said.

He said that while he first thought AU had created a culture that welcomed the alt-right’s ideology, “[maybe] the person knew this was something we wouldn’t tolerate and that they could get a rise out of us.”

Brooks said Alt-right groups aren’t seeing the desired result—more division—at AU. Instead, the university is doing more to protect students of color and other targets of white nationalist ire.

The acts of hate that these groups commit become desperate swings at an ever-improving environment of inclusivity and safety at AU. Groups like the “DC Counter Resistance” piggyback off of the media attention the university gets for its progressive policy by committing racist acts in their backyard.

Looking Forward

As for whether or not it was possible to stem the tide of hateful acts on campus, Torriente wasn’t optimistic.

“The sad truth is that it’s going to happen again, and we can’t promise it’s not going to happen again—and anyone who makes that promise to you is lying,” Torriente said. “Until we figure out a way to really eradicate [the culture of white supremacy]. It’s going to continue to be a problem — especially since it’s not someone who’s a member of the community. That’s going to make it that much harder.”

Some members of the American community are looking for solutions. Taylor Dumpson, in an interview with the Eagle from June, expressed the desire for AU’s administration to “be more consistent and work to develop a protocol” for responding to hate on campus.

Brooks offered a long-term solution that she believes will help reduce the frequency of hateful acts, not just on AU’s campus, but at all schools. It’s an idea that she says will probably increase division in the short term, but will lead to greater cohesion in the future.

Brooks says that universities have made great strides in creating environments of diversity and inclusion. However these efforts appear to be explicitly for women, people of color, and other marginalized groups, and white men have never been a part of that list, even if their inclusion is implied.

“Universities need to work to create community,” Brooks said, “and it has to include everyone.”

Torriente isn’t sold on that conclusion.

“I think, at the most fundamental level, white men are invited to the table. They don’t have to be, but they have an automatic seat in many of these discussions,” Torriente said.

He said that the issue lies in white people’s reluctance to accept some of the responsibility for racial divides within the community.

“[White people] are beneficiaries of a larger system,” said Torriente, “and [they] need to recognize that … because if we don’t have a mutual understanding of how this works, we’re not going to have a productive conversation about race … White people are invited to the conversation, just not in the friendly manner they would prefer.”

Reflecting on his experience at AU, Torriente expressed the need for students struggling with racism on campus to find like-minded people to share their experiences with.

“I think it’s important that you have space and […] find community to deal with and parse through what’s happening,” Torriente said, “and making sure that you’re taking care of yourself — that’s your number one priority.”

Ben Weiss is a sophomore studying international relations.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly cited ProPublica’s private database as the source of the 2,274 news stories covering new or developing hate crimes but that number was found on their public GNews index database, that they built in partnership with Google.