DC’s Gun Fight: One man’s standoff with Congress

Originally published in Spring 2017, Issue 21.

Graphics by Rachel Wright

On Memorial Day 2005, Timothy and Janice Heyne were docking their boat at friend Steve Mazin’s home in Thousand Oaks, California when Toby Whelchel opened fire.

He killed Janice and Steve and critically injured Timothy. Shortly after losing his mother, Christian Heyne committed himself to fighting gun violence and promoting gun control.

“Their friend [Mazin] had a restraining order against a man [Whelchel] who came and shot the friend, shot my father three times, killed my mom [then] shot a police officer, bludgeoned a mother in front of her kids and finally turned his gun on himself,” Heyne said.

“How the hell did this happen?” Heyne asked.

—

Mazin represented Whelchel in two court cases and in his Air Force court martial. Mazin took out a restraining order against Whelchel after he attacked Mazin in his own home. According to a 2005 Los Angeles Times article, Whelchel was court-martialed in 1999, fined $3,000 and discharged for failing to show up on time. Whelchel also had a criminal record in Florida, Indiana and California.

After his parents’ shooting, Heyne learned that gun laws had many loopholes.

“The gun lobby has made it easy for an illegal market of guns to run in our states,” Heyne said. “The majority of states in this country don’t require a background check to purchase a gun.”

According to California law, Heyne and others could pass local gun control ordinances. Article XI § 7 of the California Constitution allows “a county or city may make and enforce within its limits all local, police, sanitary, and other ordinances and regulations not in conflict with general laws.”

This provision gives local authorities equal power to the state legislature to protect the welfare of its residents.

The California Assembly Bill 1471, which requires guns sold in California to have a microstamp device on weapon, was a major victory for Heyne. “The microstamp intentionally stamps a code on the shell casing to trace the weapon,” said Heyne. While the bill’s passage was a small victory for gun control, there are questions surrounding the efficacy of microstamps.

“Shell casings are often [what are] left behind at shootings and what you find out is — contrary to what CSI shows tell you — it’s extremely hard to trace guns from shell casings; it only happens about one percent of the time,” said Heyne.

A series of lawsuits have been filed delaying the enactment of the bill, but Heyne is hopeful it will roll out soon and be implemented in other states.

Still, whether the bill will be enacted is uncertain. Since Republicans gained control of Congress and the White House, new legislation has been introduced to repeal Obama-era measures limiting who could buy firearms. House Resolution 90, labels gun violence a public health crisis.

According to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, titled, “Funding and Publication of Research on Gun Violence and Other Leading Causes of Death,” more than 30,000 people die every year in the U.S. from gun-related causes. That’s more than HIV, Parkinson’s disease, malnutrition and fires. Researchers hope this will lead to future studies and improved gun control efforts.

The Second Amendment and D.C.

After earning a degree in Legal Studies and a Paralegal Certificate from Chico State, Heyne moved to D.C. and began working for the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence (CSGV). CSGV has two departments: one is a 501 C4 non-profit organization, the other is a C3 organization which focuses on education. Both types are prohibited from supporting or opposing political candidates.

Founded in 1974, CSGV focuses on fighting the gun lobby and educating both leaders, as well as the public, on gun violence and gun ownership.

“The C4 [department] has cornered the market in taking on the NRA and this idea that has become politically popular of the Second Amendment being tied together with insurrectionism,” Heyne said. “[This] used to be a fringe concept and is now very much mainstream.”

Earlier this year, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals dealt a blow to the gun lobby in their decision on Kolbe v. Hogan, which chose to uphold Maryland’s ban on assault weapons. This decision overturns last year’s 2-1 decision by a Fourth Circuit panel to repeal the ban. This decision joins the Fourth Circuit with the Second, Ninth and D.C. circuits, which have upheld similar bans in other states. With this decision the Fourth Circuit approved the Maryland law forbidding the sale of assault weapons and large capacity magazines. The Kolbe decision gives gun control advocates greater standing to push for stronger federal gun laws.

Heyne believes the gun lobby will pursue an appeal to the Supreme Court in the wake of the Fourth Circuit’s decision, but there is no promise the court will hear it.

“The Kolbe decision is exciting,” Heyne said. “We’ve been looking at this administration and have asked, ‘Where are the checks?’ and have seen the courts aren’t cowering as Congress seems to be with this extreme administration.”

This decision reaffirms the Supreme Court’s ruling in District of Columbia v. Heller, where it found that handgun ownership is an individual, not collective, right. This means private citizens don’t need to belong to a militia or military group to purchase a weapon. Heller also ruled that states can ban weapons and determine who is eligible to own guns to prevent violence in their communities.

“The important takeaway is that this is a new day for assault weapons bans and is a reminder that just because the gun lobby is promoting this extreme agenda, they still have a right to regulate weapons in the states,” Heyne said.

Andrew Gottlieb, director of outreach and development at the Second Amendment Foundation, is not thrilled by the decision.

“To hear the judge say these are military weapons and shouldn’t be in civilian hands is political [and] has nothing to do with Second Amendment,” he said. “It shouldn’t have anything to do with the ruling, [it] is a personal opinion.”

Heyne doesn’t see D.C. pushing its laws any further after this decision.

“The D.C. gun death rate is lower than the national average,” he said. “Our homicide rate is higher, but I think there are a lot of reasons for that. [D.C.] is not on an island, [you] can hop on the metro and go to Virginia and buy a gun without a background check without the seller breaking the law.”

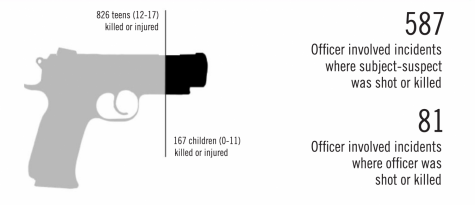

Firearms remain the primary weapon used to commit homicides in the District, according to the 2015 MPD Annual Report. They accounted for 76 percent of homicides reported in 2015. The use of firearms in homicides has increased in the past few years, from 77 in 2011 to 123 in 2015, almost a 60 percent increase in four years. The majority of homicide victims in D.C. are black males; 85 percent of victims were black men in 2015.

Homicide numbers increased in every district, save the Fourth, from 2014 to 2015. The greatest increase was in the Second where there was a 400 percent increase. It was followed by the First, Third, Seventh then Sixth. The large increases in the first two districts is due to low numbers of homicides in both years. For example in 2014 there was only one homicide in the Second District followed by five in 2015. Comparatively the Seventh District had the highest number of homicides, 54, but one of the lowest percent increases since there were 33 in 2014.

Over 1,700 firearms were recovered in 2015, with 45 percent coming from the Sixth and Seventh districts, which cover portions of the city east of the Anacostia River and southeast D.C. which includes Anacostia, Naylor Gardens and Washington Highlands.

Heyne hopes to see other states adopt similar restrictions on gun ownership.

“D.C. gun laws are emblematic of [the] need we have for national gun laws that actually try to do anything to prevent guns getting into the hands of dangerous people,” he said.

In 2010, D.C. was close to getting a representative vote in Congress on all issues, but the gun lobby tacked on a provision that would decimate all of D.C.’s gun laws, according to CBS News.

“Ultimately D.C. residents weren’t comfortable with that and after people spoke up and that bill went down,” Heyne said. “It just goes to show that it’s a disconnect and how awful it is to be a D.C. resident, not only not having a voice in Congress but don’t even have a voice in governing ourselves.”

Public Health Crisis

According to a 2013 Harvard Public Health report, 19,392 people committed suicide with guns in 2010. Suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the United States, and suicide attempts with a firearm are successful 85 percent of the time.

“We have a public health crisis,” Heyne said.

Heyne refutes the notion that nothing can be done about these statistics.

“We exist in a place where every year there are 100,000 people killed, wounded or maimed by guns and we aren’t doing anything about it,” Heyne said. “If it was a disease or car accidents, we would be all over it and right now, not only are we not all over it [but] we continue to see a push to stop any kind of regulation.”

“We’re doing nothing right now,” Heyne said. “We are doing less than the bare minimum right now.”

In 1997, the CDC was banned from doing in-depth research on gun violence after the passage of the Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations Bill, also known as the Dickey Amendment. It was named after Jay Dickey a Republican representative from Arkansas who proposed it in 1996 in response to the gun control debate heating up after the 1994 election and Clinton’s campaign on gun control legislation.

The bill contained clear and prescriptive language: “None of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.” This stipulation, along with the stripping of all funding to gun research, effectively banned gun violence research.

But Dickey never intended for the bill to be as far-reaching as it has become. Looking back, Dickey apologized for his actions.

“I wish we had started the proper research and kept it going all this time,” Dickey said to the Huffington Post in 2015.

In the wake of this bill, the CDC can only collect surveillance data (basically a count) on shootings. The information doesn’t include the circumstances surrounding a shooting, either, says Williams.

“It was never gun control [research],” Williams said. “The CDC is all about prevention of illness and injury. We don’t make regulations, we don’t enforce, we just say ‘here is the evidence, x, y, z causes x, y, z, and we recommend these guidelines.’”

Though Williams hopes the recent labelling of gun violence a public health crisis will bring change and more funding, she remains practical about its implications.

“The NRA lobby is huge and people are terrified that any kind of recommendation for prevention or safety is going to result in taking all of their guns away permanently. It’s ridiculous the mindset they have,” Williams said.

“This is a nonpartisan issue,” said Emily Hamm, President of American University’s Democrats and a sophomore from Sacramento, California. “Gun safety is something every American should care about because it’s one of the leading causes of death.”

AU Dems kick started the semester by showing a documentary on the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut. They invited Sen. Chris Murphy, (D-Conn.), to speak about the film. Since the shooting, Murphy has been a leading proponent of ‘common sense’ gun law reform.

“The film definitely showed parents and the community getting together and lobbying on behalf of victims to pass ‘common sense’ gun reform,” Hamm said.

Coming Together

According to a 2016 CNN report, nearly a third of the world’s mass shootings between 1966 and 2012 took place in the U.S, which has just five percent of the world’s population. According to the Washington Times, D.C. had seven mass shootings in 2012. In 2013, the Navy Yard in D.C. was the scene of a shooting that claimed the lives of 12 people. Despite mass shootings that seem to happen on a weekly basis — often taking the lives of children, little has been done to combat the violence.

According to Our Changing City, an initiative by the Urban Institute, D.C.’s black population has shrunk since the 1980s. Despite these decreases, black males are overwhelmingly the victims of homicides throughout the District. Based on the Urban Institute’s map of 2010 census data, the Sixth and Seventh Districts, where the majority of homicides occur, have mostly black residents. The First and Second districts, on the other hand, have mostly white and Asian residents while also having the lowest homicide rates in the city. These trends speak to the larger issue of race relations in the District and the need for greater cooperation between neighbors of different races.

“It’s about time we bring common sense to this debate,” Heyne said.

The two sides of this debate remain at odds largely due to the premise of the debate; liberals want more gun control, conservatives want less — but that doesn’t change the statistics.

“People are dying because of this,” Hamm said, “And I think we can all come together on the fact that we don’t want gun violence in America.”

From the other side, Gottlieb agrees.

“We never want to see someone killed or shot,” he said.

The number one goal of gun control supporters is passing a universal background check.

“Ninety-one percent of Americans approve this1,” Heyne said. “Seventy-four percent of NRA members agree with background checks. When I talk to people who are out fighting for gun rights and I start talking about policy, a lot of those people agree with the policies themselves.”

While Gottlieb does not find background checks useful, he said it’s an area where his side can compromise with the gun control movement to reach an agreement on reducing gun violence.

“I think if the pro-gun side came out supporting background checks…we’ll go along with it, [since it] doesn’t affect anyone purchasing a gun legally,” Gottlieb said. “[It] doesn’t stop the problem, [but] may help people see the health side is the problem, not guns.”

For Williams, the most important focus for the future is communication.

“Appeal to the other side,” she said. “Find out ‘What are your concerns? And what are your beliefs?’ And then address those concerns and those beliefs and try to find a common ground. Not just stand here on my side of the line and say ‘This side is the only side — and it’s the right side — and I’m not stepping towards you.’”

—

Despite his wins, Heyne will never forget the tragedy that brought him to the table in the first place.

“My wife will never even have the opportunity to meet my mother because we allowed a dangerous individual access to guns for … I still don’t know why,” he said. “My mom will never know her grandchildren.”

Antoinette D’Addario is a Junior studying print journalism and criminology.