Review || Art: The Migration Series, a presentation of Black flight

January 31, 2015

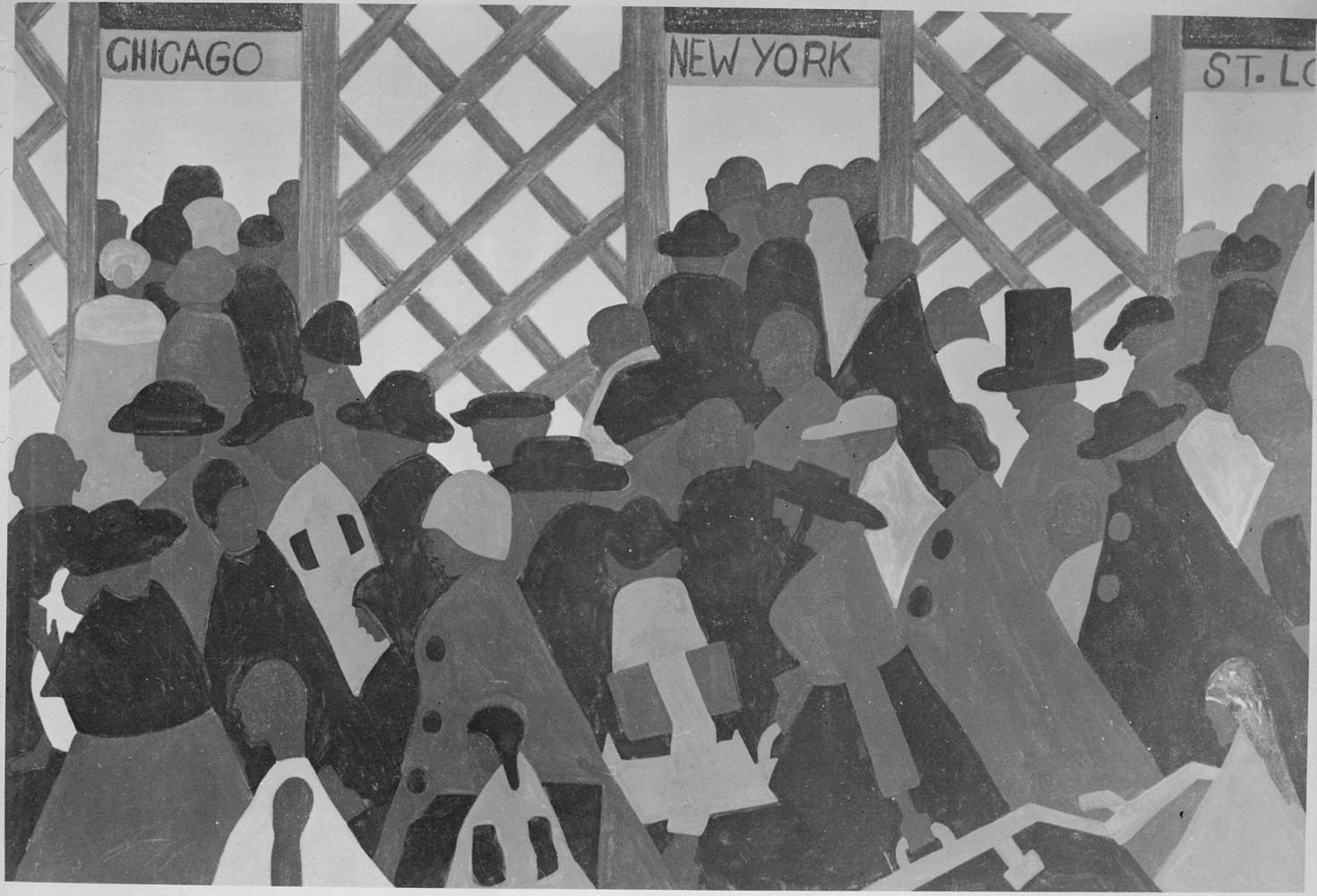

“To me, migration means movement. There was conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle came a kind of power and even beauty.” -Jacob Lawrence, artist

In the years immediately following World War I, an exodus of black migrants fled the rural South for the Northern cities in pursuit of better lives. In total, roughly 6 million African Americans moved between 1916 to 1970. Cities became overcrowded, and those who migrated soon found themselves facing prejudice, racism, and poor living and working conditions.

Artist Jacob Lawrence captured their struggle in the “the creative highlight” of his career, his “Migration Series.”

Though the series is a permanent fixture at the Phillips Collection in Dupont, only half of the 60-panel masterpiece is on display there. The other half is at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In 1942, just a year after Lawrence finished the paintings, the Phillips Collection and MoMa purchased the series jointly—the District of Columbia got the odd-numbered and New York City got the even-numbered panels.

According to museum assistants at the Phillips Collection, the entire series will be reunited for the first time in 2015. The Collection and MoMa will take turns displaying “Migrations Series” for a year, while all 60 panels will also be available on a special webpage for online viewing.

The “Migration Series” focuses on the dichotomy between the rural South and the industrial North. The South is depicted as a region marred by racism, prejudice, segregation, and poverty. While migrants hoped to leave this darkness behind, many found the same issues in the North, only this time, they faced prejudice from Northern blacks and whites alike.

Unlike Lawrence’s “Struggle Series,” painted between 1954 and 1956 and temporarily exhibited at the Collection, lines in the “Migration Series” are bold instead of slender, and shading and depth are foregone in favor of simple, uniform shapes and colors. His style seems to push the images out toward viewers, forcing them to see and try to understand instead of merely look.

While the paintings in the “Struggle Series” are titled, those titles are not as integral as they are to “Migration Series.” In the former, the images are self-explanatory. For the latter, the title allows the painting to take on a whole new meaning. Panel #51 is called “African Americans seeking to find better housing attempted to move into new areas. This resulted in the bombing of their new homes.” The buildings engulfed in spiky flames weren’t just simple structures; they were attempts to find refuge and social mobility extinguished by racism, fear, and violence.

Throughout the series, Lawrence’s motif is movement: physical movement, captured with trains, stations, and people walking, as well as social movement, represented by city hall meetings, African Americans dressed in finery and the recruitment of African American men for Northern jobs. This motif parallels the continuous movement of time—glimpsed here and there as in one panel the sun dries up crops, while in another the dawn lights up the window overlooking crowded tenement beds.

And thus viewers must move too: around the room, and through a history of a subjugated people who struggled—and continue to struggle—for equality and change. Viewers must contemplate the struggle humanity inflicts on humanity, and consider the success and failure of social movements both historical and contemporary. The paintings force them to recognize the injustice of the past in order to address injustice of the present. Viewers of the “Migration Series” must move forward.